For Further Study:

- Laurence Steinberg & Elizabeth S. Scott, Less Guilty of Reason by Adolescence: Developmental Immaturity, Diminished Responsibility, and the Juvenile Death Penalty, 58 AM. PSYCHOLOGIST 1009 (2003).

- Elizabeth Cauffman & Laurence Steinberg, (Im)maturity of Judgment in Adolescence: Why Adolescents may be Less Culpable than Adults, 18 BEHAV. SCI. LAW 741 (2000).

- Daniel Dubois and Zach Zemlin, Juvenile Offenders Before and After Graham v. Florida, Cornell Law School, Social Science and the Law

- Aliya Haider, Roper v. Simmons: The Role of the Science Brief, 3 OHIO ST. J. CRIM. L. 369 (2006).

- Margaret A. Wilson, et al., The Role of Group Processes in Terrorism, in Crime and Crime Reduction: The Importance of Group Processes 99–117 (Jane L. Wood & Theresa A. Gannon, ed. 2013).

- Kimberly Larson, Frank DiCataldo & Robert Kinscherff, Juveniles are Different: Miller v. Alabama: Implications for Forensic Mental Health Assessment at the Intersection of Social Science and the Law, 39 N.E. J. ON CRIM. & CIV. CON. 319 (2013).

- Deborah W. Denno, Courtís Increasing Consideration of Behavioral Genetic Evidence in Criminal Cases: Results of a Longitudinal Study, MICHIGAN STATE L. REV. at 987 (2011).

- Scott E. Sundby, The Jury as Critic: An Empirical Look at How Capital Juries Perceive Expert and Lay Testimony, 1109 VA L. REV. (1997)

- Patricia Wen, Admitting Guilt But Not Pleading It, Aims at Sparing Dzhokhar Tsarnaevís Life, THE BOSTON GLOBE, (Mar. 6, 2015)

- Judy Clarke is a Lawyer that Keeps Murders Off Death Row, NEWS.AU.COM, (Mar. 5, 2015 11:26 PM)

- Sheri Johnson, Preparing a Mitigation Case, February 4, 2009

Building a Mitigation Case for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev

Compiled by Alexandra McPherson, Jane Peng, and Rose Petoskey

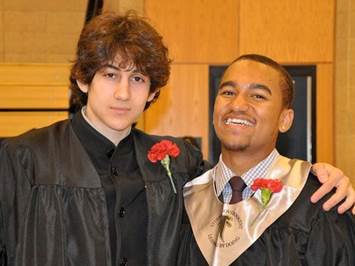

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev at his graduation from Cambridge Rindge and Latin High School in 2011.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev pictured with his siblings.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Introduction

The legal question: How can social science be used in the trial of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev to mount a case in mitigation of the death penalty?

The trial of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is currently being heard before the District Court in Boston. The defendant and his older brother Tamerlan (deceased) are accused of perpetrating the 2013 Boston Marathon bombings, which killed three people and injured over 260 others, as well as the murder of a police officer a short time after the attack. The defendant was 19 years old at the time of the charged offenses. Now 21, he is being tried on thirty counts.

The prosecution has notified the court of its intention to seek the death penalty.1 Tsarnaev’s defense team face the challenge of mounting a comprehensive mitigation case. In doing so, it is likely that they will enlist social science to argue in favor of life.

This web page will first explain the process of building a mitigation case with the aid of social science, the importance of doing so, and the key players involved in this process. It will then analyze arguments the defense team may harness in mitigation of the death penalty in the Tsarnaev case. Finally, the web page will consider lessons from pertinent case law where social science was used to argue in favor of life over death, and how this precedent can be applied in the Tsarnaev trial.

Developing a mitigation case

Why mount a mitigation case?

Defense lawyers will advance mitigating factors on behalf of their client in all sentencing proceedings. However, given the permanent and extreme nature of death as a criminal sanction, in no other context is developing a mitigation case as important as where the death penalty is sought by the prosecution. Tomes offers three reasons for presenting mitigation evidence in such cases: constitutional protections to avoid the death penalty being “imposed in an arbitrary and capricious manner;”2 the sentencing authority’s obligation to have regard to the defendant’s background before ordering death, consistently with the notion of individualized sentencing; and the practical necessity to counteract the prosecution’s case in favor of the death penalty.3

The process of developing a mitigation case

In order to mount an effective mitigation case, the defense team should carry out extensive investigations into the “social history” of the defendant.4 This demands inquiry into all facets of Tsarnaev’s life, including his upbringing, family, friends, associates, history, values, personality and psychological state at the time of the alleged offenses. Investigation of the Tsarnaev family over several generations should be undertaken in order to gain a holistic picture of the defendant. A range of methods are used to construct this social history, including interviewing and medical and psychological examinations. Social scientists are crucial to this process.

A mitigation case should explore “any basis on which the juror might decide the death penalty is not appropriate.”5 This includes any strengths of the defendant, as well as disadvantages he has faced which could account for his criminality. Professor Johnson refers to five categories of conditions often investigated: psychotic disorders, developmental and personality disorders, physical conditions that impact on mental functioning, stressors, and a global assessment of functioning.

Different jurisdictions have different legislation governing the principles to be applied when considering whether or not to sentence an accused person to death. Some statutes specifically enumerate a list of mitigating factors. However, in Lockett v. Ohio,6 the Supreme Court confirmed that a court can “not be precluded from considering, as a mitigating factor, any aspect of a defendant’s character or record and any of the circumstances of the offense that the defendant proffers as a basis for a sentence less than death.” The mitigation team must therefore investigate factors beyond those listed in the governing statute.

If this avenue is pursued, Tsarnaev’s defense team will compile a social, historical and medical history of their client and his family. Leonard observes that “the building blocks of the investigation are the collection of life history records and interviews of all significant persons in the defendant's life.”7 It is likely that the following individuals will be crucial to developing this understanding:8

- Tsarnaev’s family:

- Tsarnaev’s mother, Zubeidat;

- Tsarnaev’s father, Anzor;

- Tsarnaev’s sisters, Ailina and Bella;

- Tsarnaev’s sister, Bella;

- Tsarnaev’s uncle, Ruslan Tsarni;

- Tamerlan’s widow, Katherine Russell.

- Tsarnaev’s friends, including:

- College friends Dias Kadyrbayev, Azamat Tazhayakov and Robel Phillipos, who have been convicted in connection with destroying evidence after the bombings;

- Friend Stephen Silva, who is suspected of supplying the gun that the brothers used to kill a police officer.

- Other associates, including:

- Khairullozhon Matanov, who is a friend of Tamerlan and suspected of destroying evidence and being in contact with the brothers in the hours following the bombings;

- Tsarnaev’s childhood and university teachers, to provide developmental and learning insights;

- Medical practitioners who have treated him in connection with any emotional or physical conditions.

Interviewing family members is crucial to derive information about the family’s history, and Tsarnaev’s relationships, personality and any disturbances that could mitigate his culpability. It is also crucial to investigate the extent to which Tsarnaev was subject to the influence of his older brother at the time of the offenses. Anything at all that could mitigate Tsarnaev’s culpability is relevant.

Tsarnaev’s friends and associates can shed light on his life in America, his state of mind and associations at time of offense, his prospects of rehabilitation, and his general reputation as a person of good character prior to the alleged offenses. The mitigation team will seek out anything these individuals may know about the planning or circumstances of the offense or Tamerlan’s influence that could advance an argument in favor of life.

After compiling “a comprehensive social history of the defendant,”9 the defense team must then decide what kinds of social science assessments they need to do, including physical and psychological examinations, and will select experts accordingly. The defense team will likely use the information gathered about Tsarnaev to decide which players to enlist to advance the mitigation case; these may include social workers, neuro, clinical and educational psychologists, and personality experts. Finally, the defense team must decide which of these experts will clearly, effectively and persuasively convey mitigation arguments to the jury. Counter arguments to the prosecution’s death penalty case must also be formulated, which may involve contesting the expert opinions relied on by the state.

Mitigation specialists

In recent times, demand for the services of highly qualified mitigation specialists has escalated, particularly in high profile cases like the Tsarnaev trial. A mitigation specialist is defined as “a kind of social historian” who “gathers detailed background material about the defendant in order to persuade a jury not to impose the death penalty.”10 Guideline 4.1 of the American Bar Association’s Guidelines for the Appointment and Performance of Defense Counsel in Death Penalty Cases states that defense teams in death penalty cases shouldinclude a mitigation specialist, as well as at least two attorneys and an investigator. One of those individuals must be trained to identify mental or psychological disorders or impairments in the defendant – a role usually undertaken by the mitigation specialist.11 Mitigation specialists fill a perceived gap in the skills of typical defense lawyers, who are not necessarily trained in social sciences and thus not well placed to build a persuasive mitigation case. Lawyers are trained to uncover “what” happened; mitigation specialists are trained to discover “why.”12

The effectiveness of mitigation specialists has been expressly attested to by the United States Supreme Court. In a series of cases, the Court stressed “the importance of thorough capital mitigation investigation” as a fundamental component of providing effective counsel as mandated by the Sixth Amendment.13 Failing to use a mitigation specialist “will increase the risk that counsel will miss vital mitigating evidence.”14 The indispensability of mitigation specialists was confirmed by a report on the costs of federal death penalty cases, compiled by a Parliamentary Subcommittee in 1998, which drew on qualitative and quantitative research on a range of issues.15 Lawyers and judges in over half of the jurisdictions that authorized the death penalty at the time of the report were interviewed about their perspectives on mitigation specialists. The Subcommittee found that:

| without exception, the lawyers interviewed…stressed the importance of a mitigation specialist to high quality investigation and preparation of the penalty phase. Judges generally agreed with the importance of a thorough penalty phase investigation, even when they were unconvinced about the persuasiveness of particular mitigating evidence offered on behalf of an individual defendant. The work performed by mitigation specialists is work which otherwise would have to be done by a lawyer, rather than an investigator or a paralegal. Because the hourly rates approved for mitigation specialists are substantially lower than those authorized for attorneys, the appointment of a mitigation specialist or penalty phase investigator generally produces a substantial reduction in the overall costs of representation.16 |

Mounting the Case for Mitigation in the Tsarnaev Trial

Many commentators have stated that the guilt-or-innocence phase of the trial “is a foregone conclusion.”17 The wealth of evidence showing Tsarnaev’s involvement in the bombing will likely lead to a guilty verdict, and his defense lawyer even admitted during her opening statement, “It was him.”18 Thus, his defense team will focus both at trial and at sentencing on making a strong case against the death penalty. The defense will present him as a young man who has been wholly shaped by his older brother Tamerlan, ultimately influenced to carry out his brother’s plan of the Boston Marathon bombing. The portrayal of Tsarnaev as a “follower” manipulated by his older brother will likely take prominence during the mitigation phase. However, because mitigating factors can include any reasonable basis on which a jury could conclude that the death penalty is not the appropriate penalty,19 there is a long list of possible factors that his defense team could include in his case for mitigation. Mirroring the mitigating factors under 18 U.S.C. § 3592 that a fact-finder must consider in determining whether to impose the death penalty, possible factors include:

- his older brother’s influence and coercion

- his age and impaired capacity

- his status and experience as a refugee

- his lack of a criminal record

- his good reputation in school and in the community

- religious and moral influences

- personality or social disorders

In the following sections, we will focus on Tsarnaev’s age and Tsarnaev’s brother’s influence on him. We will explain the social science research behind these mitigating factors and how it can be used to mount a successful mitigation case for Tsarnaev.

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s Age

Social science research behind the impact of adolescence and youth on an offender supports the idea that juvenile offenders should not be held to the same standards of criminal responsibility as adults.20 Research has shown that the levels of cognitive and psychosocial developments in adolescents tend to both influence their decision-making capacity and make them more vulnerable to coercion or duress. For a good summary of such research, see the Social Science and the Law student project webpage on juvenile offenders.21

Additionally, age has been shown to be an effective mitigating factor. Death sentences were rare for juveniles even before the Supreme Court held them to be unconstitutional. As of December 31, 2004, 71 juveniles were on death row, which represented 2% of the total death row population. All of the offenders were sixteen or seventeen years-old.22 For a state-by-state breakdown of the juvenile death sentences imposed between 1973 to 2000, see the DOJ’s report, Juveniles and the Death Penalty.23 This report also shows that the vast majority of offenders were seventeen years-old at the time of the crime and that as age decreases (from seventeen to sixteen and fifteen), the frequency of the imposition of the death sentence drops dramatically.24

Indeed, the Supreme Court has also endorsed the view in forensic psychology that significant cognitive, emotional, behavioral differences exist between adults and juveniles. In the landmark case of Roper v. Simmons,25 the Court held that the death penalty was a disproportionate punishment for juvenile offenders. Then in Graham v. Florida26 and Miller v. Alabama,27 the Court held that mandatory life imprisonment without parole for juvenile offenders violated the Eighth Amendment’s protection against cruel and unusual punishment. In each of these cases, the Court’s rationale rested on an understanding that children and adolescents are constitutionally different from adults because they lack maturity and sense of responsibility, are more susceptible to negative influences, lack the ability to control their own environment, and possess fewer fixed traits.28 Much of this understanding came from the social science research marshaled for the defendants in these cases; for an in-depth discussion of the role the science behind juveniles’ cognitive and psychosocial development played in Roper, see Aliya Haider, Roper v. Simmons: The Role of the Science Brief.29 In the following subsections, we will examine the two most relevant social science findings about adolescents’ developmental immaturity: deficiencies in decision-making and heightened vulnerability to influence or coercion.

1) Deficiencies in Decision-making:

There is much social science research establishing that adolescents’ levels of cognitive and psychosocial development differ from that of adults. This immature cognitive and psychosocial development shapes adolescents’ decision-making and autonomy. “[B]ecause adolescents are still in the process of forming their personal identity, their criminal behavior is less likely than that of an adult to reflect bad character.”30

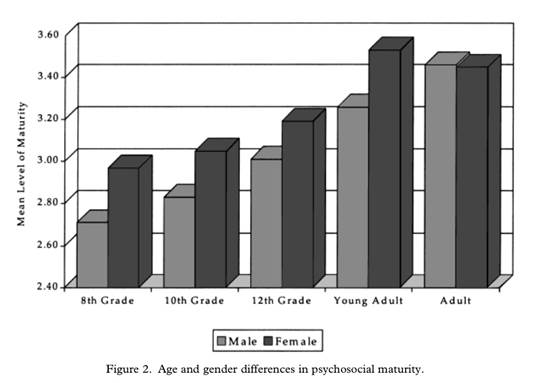

Laurence Steinberg and Elizabeth Cauffman conducted a study in which they hypothesized that “maturity of judgment” consisted of three elements: responsibility, perspective, and temperance. Those who are responsible, temperate, and circumspect will make better decisions. They tested this hypothesis by examining whether these qualities affected the decisions that participants make under various circumstances. Their sample consisted of more than 1,000 eighth, tenth, twelfth grade students, and college students of diverse race, gender, socioeconomic status, and academic performance in the Philadelphia area. The study asked in the participants in a questionnaire to describe themselves (to assess responsibility, perspective, and temperance) and then asked them to choose how they would respond in different scenarios involving antisocial behavior (smoking marijuana, shoplifting, etc.).31

The results suggest that antisocial decision-making is negatively correlated with psychosocial maturity (as measured by levels of responsibility, perspective, and temperance) and that psychosocial maturity increases with age. Their findings are laid out in the following summary chart:

From: Elizabeth Cauffman & Laurence Steinberg, (Im)maturity of Judgment in Adolescence: Why Adolescents may be Less Culpable than Adults, 18 Behav. Sci. Law 741, 754 (2000).

They also found that responsible decision-making does not appear to increase much after age nineteen but that the steepest inflection point in the developmental curve occurs between age sixteen and nineteen, making this period “an important transition point in psychosocial development that is potentially relevant to debates about the drawing of legal boundaries between adolescence and adulthood.”32 This no doubt has important implications for defendants such as Tsarnaev, who was nineteen at the time of the crime.

2) Heightened Vulnerability to Influence or Coercion

Especially in settings conducive to criminal activity, adolescents do not make decisions in a vacuum (such as in a laboratory setting) but in an environment of peer pressure, stress, and emotional arousal. Because adolescents’ cognitive and psychosocial levels of development are less mature than that of adults, adolescents are also more susceptible to outside influences and pressures. Criminal law usually measures duty and culpability based on a “reasonable, ordinary person” standard. Social scientists have argued, however, that juveniles’ behavior should not be measured against the behavior of an ordinary adult, but rather, an ordinary juvenile of the same age.33

The psychosocial factors that are most relevant to understanding differences in judgment and decision-making are (a) susceptibility to peer influence, (b) attitudes toward and perception of risk, (c) future orientation, and (d) the capacity for self-management.34 Adolescents are generally more susceptible to peer pressure, more likely to take risks, less likely to think about future consequences, and “lack the freedom that adults have to extricate themselves from a criminogenic setting,” such that the same level of duress or pressure will likely have a more disruptive and influential impact on adolescents than adults.35

At the time of the bombing, Tsarnaev was nineteen years old. Although legally an adult, he did not necessarily have the mental capacity and psychosocial development of an adult. In fact, in his most formidable years, what Cauffman and Steinberg call an “important transition point,” he was exposed to the influence of his older brother, Tamerlan, and Tamerlan’s extremist views. He was likely susceptible to not only peer pressure but also to the religious extremism that would ultimately mark his actions. Thus, his age and immature levels of cognitive and psychosocial development likely played a large part in his decision to help his brother carry out such a destructive plan.

Tamerlan Tsarnaev’s Influence on His Brother

“He was like a puppy dog following his older brother,” John Curran, Tamerlan Tsarnaev’s boxing coach, said of Dzhokhar.36 As the elder of the two brothers, Tamerlan exerted a large amount of influence on Dzhokhar, and his story cannot be extricated from that of Dzhokhar’s. In the wake of the bombing, Tamerlan and Dzhokhar went on the run and, while engaging in a shootout with police officers, Tamerlan was shot and killed. Although Tamerlan is no longer available to testify or stand trial, there is evidence that Tamerlan was the “mastermind” behind the bombing and likely influenced his brother to participate.

At twenty-six years old at the time of the Boston Marathon bombing, Tamerlan was the older brother of the family. The Tsarnaev family members were refugees who fled war-torn Chechnya for America a decade ago. They received asylum and lived in Cambridge, just outside of Boston. Tamerlan was a gifted athlete who was described as “known for his flashy clothes and in-your-face self-confidence.”37 A devout Muslim, Tamerlan claimed to have no American friends despite having an American wife. He spent about six months in Dagestan, Russia in 2012, a trip in which authorities believe he may have made contact with extremists. He had also been a suspect in the unsolved 2011 Waltham triple homicide, a crime for which his friend, Ibragim Todashev (now deceased) implicated him.38 In comparison, Dzhokhar was often described by friends and community members as “introverted,” “quiet,” and “passive.”39

These accounts seem to suggest that Tamerlan likely exerted a large influence on Dzhokhar; as an older, more assertive, dominant sibling, the pressures he placed on Dzhokhar would likely have been even stronger than that from Dzhokhar’s peers. The testimony from community members also suggests that Dzhokhar looked up to Tamerlan. This reverence of Tamerlan, in conjunction with Dzhokhar’s young age and heightened vulnerability to external pressures, probably made Dzhokhar extremely susceptible to becoming influenced or coerced to participate in the crime.

Additionally, there has been some research (albeit quite old) about the group context on decision-making. “Risky shift” research has shown that individuals take more risks and otherwise make decisions differently in groups than as individuals, specifically in crime or terrorism contexts.40 All these factors combined—Dzhokhar’s age, his cognitive and psychosocial immaturity, Tamerlan’s influence on him, the group context in decision-making—make a persuasive case for mitigation.

The Work of Judy Clarke and the Use of Lay and Expert Witnesses

Attorney Judy Clarke is part of Tsarnaev’s defense team and she is known for keeping her clients off of death row. 41 Judy Clarke has successfully argued for life in prison rather than the death penalty for many high profile criminal defendants, including Susan Smith (a mother from South Carolina convicted of drowning her two sons), Ted Kacynski (better known as the “Unabomber.”), Eric Rduloph (Atlanta Olympics bomber), and Jared Loughner( shot 19 people at a supermarket in Tucson, AZ including U.S. Representative Gabrielle Giffords). 42 Although it is difficult to compare the specific factual settings of each case Judy Clarke has worked on, it is helpful to review her mitigation strategies and how she may employ these strategies in the Tsarnaev trial. In her opening statement in the Tsarnaev trial Judy Clarke conceded that Tsarnaev is guilty of committing the Boston Marathon bombing, stating that Tsarnaev committed a “series of senseless, horribly misguided acts.”43 The strategy of admitting guilt, but not pleading guilty is often employed in death penalty cases where there is significant evidence showing the defendant is guilty. An integral part of successful mitigation cases is balancing the use of lay and expert testimony on the mitigating factors focused on by the defense. In the following sections, we will provide background on the use of lay and expert witnesses in mitigation cases by reviewing an empirical study on the effectiveness of witness testimony in capital cases, as well as review the use of expert and lay witness testimony in the Susan Smith case as an example of the balance between expert and lay witnesses that may be used in the Tarnaev trial.

The Use and Effectiveness of Expert and Lay Witnesses in a Mitigation Case

In “The Jury as Critic: An Empirical Look at How Capital Juries Perceive Expert and Lay Testimony” Professor Scott Sundby presents an assessment of how juries in capital case view expert and lay witness testimony. 44 Sundby draws on data from the Capital Jury Project that was funded by the National Science Foundation with the goal of studying how juries made decisions in capital cases.45 Sundby examined the use of expert and lay testimony in 36 different capital cases in California, 18 of which resulted in a death sentence, 17 decided to sentence the defendant to life without parole. 46 Sundby found that the use of experts in the “penalty phase” (the phase in which the prosecution is arguing for the death sentence and the defense is arguing for life) is very high, finding that in 30 out of the 36 cases a professional expert was called to testify. 47 Sundby asked the capital jurors the following questions: “whether, for the prosecution or defense, any guilt-phase witnesses were particularly hard to believe, what evidence or testimony was most influential at the penalty phase, and whether any penalty evidence ‘backfired’”48 Sundby found that overall jurors tend to react negatively when professional experts (e.g. doctors or psychiatrists that are paid to testify applying their expertise to the case) testify for the defense.49 In fact, Sundby found that “jurors’ impressions of defense expert witnesses were more than twice as likely to be negative rather than positive.”50 On the other hand witnesses who were family and friends of the defendant, testifying for the defense were viewed by most of the jurors as having positive influence on the defense’s case. 51 Sundby also assessed another category of experts, which he terms “lay experts”, meaning people who knew the defendant but were not friends or family. These witnesses draw their expertise from experiences with the defendant not from training in a particular field.52 For example a lay expert could be a prison guard who interacted with the defendant.53 Sundby found that although professional experts were used more often, lay experts were the most likely to be named as the “most influential witness” when they did testify. 54

Sundby also articulates that defense professional experts are remembered the most by jurors (finding that in 20 out of 30 cases defense professional expert were cited as the most memorable), but jurors tend to find that they are not credible.55 Although many jurors perceived defense professional experts to not be credible, when the juror does get a positive impression from the professional expert, the effect is seen in the juror’s ultimate decision to grant a life sentence rather than a death sentence. Sundby notes that in six cases where a defense professional expert received a positive impression from the jurors, a life sentence was given in each case. 56 Interestingly, Sundby also found that many jurors do not think of the legally defined mitigating factors as actually mitigating.57 Sundby found that many jurors indicated that having a bad childhood, or a mental illness, or past drug abuse etc. did not in any way excuse the actions of the defendant to the extent that the defendant should be given life in prison and not sentenced to death. 58 The Sundby study is one of the only empirical studies that we could find that attempts to measure the effectiveness of expert and lay witnesses in capital cases.

The Sundby study is small and was only done in one state, so it is certainly not representative of the use of lay and expert witnesses generally. We hypothesize that there are not many studies in this area because building a mitigation case varies widely dependent on the unique life experiences of the defendant, so it is difficult to make general conclusions about the effectiveness of the use of particular witnesses. Nonetheless, Subdby’s findings are interesting and instructive on the use of expert and lay witnesses in capital cases.

The Susan Smith Case: Use of Expert and Lay Witnesses

Although the study conducted by Sundby paints a rather grim picture of the use of expert and lay witnesses in mitigation cases, Judy Clarke has successfully employed the use of lay and expert witness testimony to achieve a life sentence for her clients facing the death penalty. This section will review the use of expert and lay witnesses put together by Judy Clarke in the Susan Smith case. Susan Smith was convicted of drowning her two sons by allowing her car to go into a lake with her two sons trapped inside. Smith’s defense team, including Judy Clarke, centered their mitigation case around Smith’s lifelong battle with depression and abusive upbringing. 59 In her opening statement Clarke stated: “This is not a case about evil….this is a case about despair and sadness.”60 The defense argued that Smith was in a “depressive crisis”, and therefore unable to act rationally, and attempted to commit suicide with her two children in the car and then realized she did not want to commit suicide and jumped from the car and was unable to remember her children were in the car. 61 The defense presented several professional expert witnesses to support their mitigation case. Dr. Seymour Halleck (a medical doctor) testified that there was a very high incidence of depression and mental illness in Smith’s family, and this increased Smith’s chances of eventually coming into a depressive state.62

Additionally, Dr. Arlene Andrews (a social worker) testified and presented a “genogram” showing several depression related behavioral disorders in Smith’s family that went back three generations.63 Dr. Andrews testified that the separation of Smith’s parents, the suicide of her father, and Smith’s stepfather’s molestation of Smith all were contributing factors to her ultimate “dependent depressive disorder”, which caused Smith to need immediate and continual love and attention from everyone in her life, and when this attention was lost Smith would be overwhelmingly distraught. 64 Dr. Andrews also testified about the causes behind Smith’s suicide attempts at the ages of thirteen and eighteen. Dr. Andrews stated that Smith’s suicide attempt at thirteen was the result of her molestation by her stepfather that made Smith feel torn between possibly losing her stepfather while also knowing that he was doing was wrong. 65 Additionally, Dr. Andrews testified that Smith’s suicide attempt at the age of eighteen stemmed from her fear of losing sexual relationships with her supervisor and co-worker. 66

Lay witness testimony provided by Smith’s brother and many other family members and friends about Smith’s upbringing also supported the defense’s argument that Smith had suffered many traumatic abusive experiences within her family as a child and young adult.67 The defense presented a picture of lifelong mental trauma that began for Smith at a very early age, and caused Smith to be in a continually depressive state for the majority of her life.68

The Tsarnaev Case: Potential Use of Expert and Lay Witnesses

Although each mitigation case is certainly different dependent on the unique defendant and the unique crime, some things may be learned from the use of the expert and lay witnesses in the Susan Smith case as well as the Sundby study that may be applicable to the Tsarnaev case. It seems apparent from the findings of the Sundby study as well as from the Susan Smith case that it is most effective to use a mix of expert and lay witnesses when making a case for mitigation. As the Sundby study indicated, jurors seem to be skeptical of expert witnesses on the defense side but more open to believing the testimony of family and friends. However, expert testimony for the defense, in cases in which the jury believes the expert, can be a very persuasive factor in the jury’s ultimate decision of life or death.

So far in the Tsarnaev trial, the prosecution has been presenting witness testimony from survivors of the bombing as well as emergency workers.69 The testimony of the father of a young boy who died in the bombing has been cited by media sources as particularly heart wrenching and moving, causing many jurors to cry.70 The defense has not sought to cross-examine any of the witnesses since the defense has admitted that Tsarnaev committed the bombing.71 Predicting the witnesses that the defense will ultimately call as the trial moves forward is difficult. However, based on the information reviewed here the defense will likely put forward several witnesses who are Tsarnaev’s friends and family members to lay the groundwork to a tell story of Tsarnaev’s upbringing and how various life events have left a negative impact on him. Many jurors that served in the Susan Smith case indicated in interviews after their decision that the stories told of Smith’s traumatic upbringing were especially persuasive in their decision to sentence her to life. 72 Additionally, the defense may call some experts to testify about the impact of Tsarnaev’s age, and how he was not fully psychologically developed at the time of the bombings. In her opening statement Judy Clarke stated that Tsarnaev wad led down “a path borne of his brother, created by his brother and paved by his brother.”73 Thus, it is also likely that the defense may call experts to testify about the scale of influence that Tamerlan Tsarnaev had on his younger brother, and the significance of this influence. Furthermore, it is also possible that the defense will call what Sundby terms “lay experts”, people who have had experiences with the Tsarnaev brothers that may directly support various mitigating factors.

1 United States v. Tsarnaev, Notice of Intent to Seek the Death Penalty, No.13-10200-GAO (D. Mass. Jan. 30, 2014)

2 Jonathan Tomes, Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don't: The Use of Mitigation Experts in Death Penalty Litigation, 24 Am. J. Crim. L. 359, 362 (1997); Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 188 (1976) (summarizing the holding in Furman).

3 Jonathan Tomes, Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don't: The Use of Mitigation Experts in Death Penalty Litigation, 24 Am. J. Crim. L.359, 361-62 (1997).

4 Sheri Johnson, Preparing a Mitigation Case, February 4, 2009.

5 Sheri Johnson, Preparing a Mitigation Case, February 4, 2009.

7 Pamela Blume Leonard, A New Profession for an Old Need: Why a Mitigation Specialist Must be Included in the Capital Defense Team, 31 Hofstra L. Rev. 1143 (2002-2003).

8 Zeninjor Enwemeka, Who’s Who in the Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Trial, WBUR (Mar. 6, 2015, 12:51 PM)

9 Pamela Blume Leonard, A New Profession for an Old Need: Why a Mitigation Specialist Must be Included in the Capital Defense Team, 31 Hofstra L. Rev. 1143 (2002-2003).

12 Pamela Blume Leonard, A New Profession for an Old Need: Why a Mitigation Specialist Must be Included in the Capital Defense Team, 31 Hofstra L. Rev. 1143, 1151 (2002-2003).

13 Emily Hughes, Mitigating Death, 18 Cornell J. L. & Pub. Pol'y 337, 339 (2008-2009); Williams v. Taylor 529 U.S. 362 (2000); Wiggins v. Smith 539 U.S. 510 (2003); Rompilla v. Beard 545 U.S. 374 (2005).

14 Pamela Blume Leonard, A New Profession for an Old Need: Why a Mitigation Specialist Must be Included in the Capital Defense Team, 31 Hofstra L. Rev. 1143, 1151 (2002-2003).

15 Federal Death Penalty Cases: Recommendations Concerning the Cost and Quality of Defense Representation, Report for the Subcomm. on Federal Death Penalty Cases, Comm. on Defender Services, Judicial Conference of the United States, at II (May 1998), (Hon. James R. Spencer, Subcomm. Chair).

17 Tsarnaev’s Lawyer Admits He Carried Out Boston Bombing, WVCB (Mar. 4, 2015, 11:25 PM)

18 Ann O’Neill & Mariano Castillo, Tsarnaev Attorney: “It was Him,” CNN.com,http://www.cnn.com/2015/03/04/us/boston-marathon-bombing-trial/.

19 Sheri Johnson, Preparing a Mitigation Case, February 4, 2009.

20 See Laurence Steinberg & Elizabeth S. Scott, Less Guilty of Reason by Adolescence: Developmental Immaturity, Diminished Responsibility, and the Juvenile Death Penalty, 58 Am. Psychologist 1009 (2003).

21 Daniel Dubois & Zach Zemlin, Juvenile Offenders Before and After Graham v. Florida, Cornell Law School Social Science and the Law.

22 Victor L. Strieb, Juvenile Offenders Who Were on Death Row, Death Penalty Information Center.

23 Lynn Cothern, Juveniles and the Death Penalty, DOJ (Nov. 2000).

28 See Kimberly Larson, Frank DiCataldo & Robert Kinscherff, Juveniles are Different: Miller v. Alabama: Implications for Forensic Mental Health Assessment at the Intersection of Social Science and the Law, 39 N.E. J. on Crim. & Civ. Con. 319 (2013).

30 Laurence Steinberg & Elizabeth S. Scott, Less Guilty of Reason by Adolescence: Developmental Immaturity, Diminished Responsibility, and the Juvenile Death Penalty, 58 Am. Psychologist 1009, 1011 (2003).

31 Elizabeth Cauffman & Laurence Steinberg, (Im)maturity of Judgment in Adolescence: Why Adolescents may be Less Culpable than Adults, 18 Behav. Sci. Law 741 (2000).

33 Laurence Steinberg & Elizabeth S. Scott, Less Guilty of Reason by Adolescence: Developmental Immaturity, Diminished Responsibility, and the Juvenile Death Penalty, 58 Am. Psychologist 1009, 1014 (2003).

36 Jon Schuppe, Brothers’ Classic Immigrant Tale Emerges as Relatives Speak Out, NBC Bay Area (Jul. 1, 2013, 10:48 AM).

37 Deborah Feyerick, Tsarnaev’s Connections: Who’s Who, Cnn.com (Mar. 4, 2015, 12:58 PM).

38 Zeninjor Enwemeka, Who’s Who in the Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Trial, WBUR (Mar. 6, 2015, 12:51 PM).

39 Jon Schuppe, Brothers’ Classic Immigrant Tale Emerges as Relatives Speak Out, NBC Bay Area (Jul. 1, 2013, 10:48 AM).

40 See Margaret A. Wilson, et al., The Role of Group Processes in Terrorism, in Crime and Crime Reduction: The Importance of Group Processes 99–117 (Jane L. Wood & Theresa A. Gannon, ed. 2013).

41 Judy Clarke is a Lawyer that Keeps Murders Off Death Row, News.au.com, (Mar. 5, 2015 11:26 PM).

42 Erin Donaghue, Defending Dzhokhar Tsarnaev: Renowned Attorney Judy Clarke Will Fight for Bombing Suspect’s Life, CBS News, ( May 2, 2013 2:46 PM).

43 Patricia Wen, Admitting Guilt But Not Pleading It, Aims at Sparing Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s Life, The Boston Globe, (Mar. 6, 2015)

44 Scott E. Sundby, The Jury as Critic: An Empirical Look at How Capital Juries Perceive Expert and Lay Testimony, 1109 VA L. Rev. (1997).

59 See Deborah W. Denno, Courts’ Increasing Consideration of Behavioral Genetic Evidence in Criminal Cases: Results of a Longitudinal Study, Michigan State L. Rev. 967, 983-984 (2011) ( summarizing the arguments made at the penalty phase of the trial as well as the use of expert and lay witnesses by the defense ).

60 Ann O’Neil, Tsarnaev Lawyer Keeps Hated Criminal Off Death Row, CNN.com (May 2, 2013 10:40 AM).

69 See Katherine Q Seelye and Jess Bighood, Accounts of Heartbreak in Tsarnaev Trial as Victims of Boston Marathon Bombings Testify, NY Times (Mar. 5, 2015).

70 See Hilary Sargent, Eric Levenson, and Hannah Sparks, Updates from Boston Marathon Bombing Trial: Father of Martian Richard Gives Emotional Testimony, Boston.com (Mar. 4, 2015, 2:09 PM).

71 See Katherine Q Seelye and Jess Bighood, Accounts of Heartbreak in Tsarnaev Trial as Victims of Boston Marathon Bombings Testify, NY Times (Mar. 5, 2015).

73 Katherine Q. Seelye and Richard A. Oppel Jr., Opposing Pictures of Tsarnaev at Boston Marathon Bombing Trial, NY Times, (Mar. 2, 2015).