For Further Study:

- Boston Marathon Terror Attack Fast Facts

- The Boston Globe, 'It was him,' defense admits as Marathon bombing trial begins

- Business Insider, Here's why the Boston Bomber pleaded not guilty even though his lawyer told the court he did it

- Death Penalty Information Center, Introduction to the Death Penalty

- Brent Tarter, Lawes Divine, Morall and Martiall, Encyclopedia Virginia

- Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972).

- Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976).

- Department of Justice, The Federal Death Penalty Act of 1994

- United States v. Sampson, 335 F. Supp. 2d 166 (D. Mass. 2004).

- Notice of Intent to Seek the Death Penalty, Case 1:13-cr-10200-GAO Document 167

- Isaac Ehrlich, The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment: A Question of Life and Death. 65 Am. Econ. Rev. 397 (1975).

- Jeffrey Fagan, Capital Punishment: Deterrent Effects & Capital Costs

- Memorandum of Lawrence A. Greenfeld to Steven R. Schlesinger (Dec. 18, 1985).

- Hugo Adam Bedau, An Abolitionist’s Survey of the Death Penalty in America Today, in Debating the Death Penalty 15, 18 –22 (2004).

- Paul Cassell, In Defense of the Death Penalty (2008), in Debating the Death Penalty 183, 189 (2004).

- Robert M. Bohm, The Death Penalty Today 126-127 (2008).

- Hashem Dezhbakhsh, Paul H. Rubin, & Joanna M. Shepherd, Does Capital Punishment have a Deterrent Effect: New Evidence from Post-Moratorium Panel Date, 26 –27. Margin of error of 10 and a corresponding to a 95% confidence interval (8 to 28).

- Senator Hatch, Sen. Rep. No. 107-315, The Innocence Protection Act of 2002, 107th Cong., 2d Sess. 89 (Oct. 16, 2002); Paul Cassell, In Defense of the Death Penalty (2008), in Debating the Death Penalty 183, 185 (2004).

- United States v. McVeigh, 153 F.3d 1166 (Sept. 8, 1998).

- Florida Capital Resource Center, Victim Impact Statements

- The Boston Globe, 'It was him,' defense admits as Marathon bombing trial begins

- Barefoot v. Estelle 463 U.S. 880 (1983).

- John Monahan, The Clinical Prediction of Violent Behavior: Crime and Delinquency Issues, 1981.

- Payne v. Tennessee 501 U.S. 808 (1991).

- Booth v. Maryland 482 U.S. 496 (1987).

- Amicus brief in Roper v. Simmons 543 U.S. 551 (2005) by the American Medical Association et. Al.

- Valerie P. Hans, The Impact of Victim Participation in Saiban-in Trials in Japan: Insights from the American Jury Experience, 42 Int’l J.L. Crime & Just. 111 (2014).

Making a Case for the Dealth Penalty in the Tsarnaev Case

Compiled by Brittany Benavidez, and Seong Huon Lee

Victims of the Boston Marathon bombing

LEGAL ISSUE

On April 15, 2013 Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and his brother, Tamerlan planted two explosives at the Boston Marathon. The explosions reportedly killed three people, one of which was an eight-year-old boy, and injured over 260 others, 16 of which had their limbs amputated (click here to see one of the amputee victims, warning graphic content). Three days later Dzhokhar and Tamerlan also killed a police officer working for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Two years ago Dzhokhar Tsarnaev pleaded not guilty to the charges brought against him but just last week Tsarnaev’s attorney Judy Clarke said in her opening statement, “[i]t was him” and that “[t]here’s little that occurred the week of April the 15th . . . that we dispute.”

Guilt is not the burning question in this case. Many believe the guilt phase of this trial is purely a means for the defense to view all of the government’s evidence and arguments in order to help them prepare for the penalty phase. The legal issue in the Tsarnaev case is whether he will be sentenced to death when he is convicted. Based on social science supporting the death penalty and its deterrent effects, the extensive list of aggravating factors against him, and social science rebutting what will likely be a mitigating factor offered by the defense, the prosecution has a strong case for the death penalty.

HISTORY OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE UNITED STATES

The execution of Captain George Kendall for working as a spy for Spain in Jamestown, Virginia in 1608 is the first recorded execution in the American colonies (Death Penalty Information Center). In 1610, Virginia passed the Lawes Divine, Morall and Martiall, which allowed the use of the death penalty for both serious and minor criminal offenses. Some of the crimes subject to the death penalty included religious blasphemy, murder, sodomy, robbery, swearing false oaths, bearing false witness, unauthorized trading with Indians, stealing from Indians, unauthorized trading with sailors, and unauthorized shipping of goods (Encyclopedia Virginia). The laws on death penalty differed for each colony.

In 1972, in Furman v. Georgia, the U.S. Supreme Court held that Georgia’s death penalty statute, which provided the jury with complete sentencing discretion, could produce arbitrary capital punishment decisions. The Court held that the imposition of the death penalty under the statute constitutes cruel and unusual punishment and therefore violates the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments. This decision effectively nullified forty death penalty statutes throughout the United States. However, that nationwide suspension ended three years later with Gregg v. Georgia, which held that the imposition of the death penalty does not automatically violate the Constitution.

LAYING OUT A CASE FOR THE DEATH PENALTY

One important federal statute that authorizes the death penalty is the Federal Death Penalty Act of 1994 (codified at 18 U.S.C. §§ 3591-3598). In passing the Federal Death Penalty Act, Congress set constitutional procedures for imposing the death penalty for sixty offenses under thirteen existing and twenty-eight new Federal capital statutes (U.S. Department of Justice).

During a capital case in which the government seeks to impose the death penalty, the Federal Death Penalty Act bifurcates the trial into either the guilt phase or the penalty phase. United States v. Sampson, 335 F. Supp. 2d 166, 175 (D. Mass. 2004). The penalty phase takes place only when the defendant is proven guilty of a capital offense. Id. The jury faces two distinct issues during the penalty phase. Id. The jury first decides whether the defendant is eligible for the death penalty. If the defendant is found death-eligible, the jury needs to decide whether a death sentence is justified.

To establish the defendant’s eligibility for a death sentence for a capital offense, the government must prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, the following three criteria: that the defendant was at least 18 years old at the time of the crime (18 U.S.C. § 3591(a)); that the defendant acted with one of the four mental states listed in 18 U.S.C. § 3591(a)(2); and that at least one of the sixteen statutory aggravating factors listed in 18 U.S.C. § 3592(c) exists.” Id. at 175-76. If the government fails to establish that the defendant is death-eligible, the court cannot impose a death sentence against him.

In deciding whether the death penalty is justified, the jury must weigh all relevant aggravating factors against all relevant mitigating factors. Id. at 176. For the defendant to receive the death sentence, the jury must unanimously conclude that all the applicable aggravating factors outweigh all the mitigating factors to justify a death sentence, or, if there are no existing mitigating factors, the aggravating factors themselves are sufficient to justify a death sentence. Id. Aggravating factors can consist of both statutory aggravating factors and non-statutory aggravating factors asserted in the government’s notice of intent to seek the death penalty. Id. Likewise, mitigating factors can consist of any relevant circumstances that could influence a jury to reject the imposition of the death penalty.

WHY SHOULD WE PERMIT THE DEATH PENALTY?

There are two justifications why the death penalty should be permitted in the United States. Both justification are informed by social science research.

INCAPICITATION

Perhaps the most straightforward argument for the death penalty is that it saves innocent lives by preventing convicted murderers from murdering again. In a study of 52,000 state prison inmates serving time for murder, researcher Lawrence A. Greenfeld found an estimated 810 inmates had previously been convicted of murder and had killed 821 innocent people following those convictions. Memorandum of Lawrence A. Greenfeld to Steven R. Schlesinger (Dec. 18, 1985), quoted in Paul Cassell, In Defense of the Death Penalty (2008). If even a fraction of these murderers had received the death penalty after their first conviction, many innocent lives would have been saved.

While social science research, such as the study done by Mr. Greenfeld, demonstrates the legitimacy of the incapacitation argument, this argument is not without its concerns. First, Mr. Greenfeld’s own study showed that only a fraction of murderers (1.5%) murdered again. Second, only a fraction of murderers—the “worst of the worst”—receive the death penalty. As a result, capital punishment would not prevent allmurderers, or even most, from murdering again. Lastly, social scientists against capital punishment argue that the death penalty is not the only form of punishment that is successful at incapacitation. Specifically, they argue “life without the possibility of parole” also saves innocent lives without requiring the taking (deserved or not) of another.

In addressing these “weaknesses,” abolitionist and advocates of the death penalty continue to disagree about the moral justifications of the death penalty. However, advocates argue the first two concerns—how many murderers murder again and how many murderers are given the death penalty—support their position that the death penalty saves, albeit at a lower rate then desired, innocent lives.

The incapacitation argument remains a valid argument that uses social science to support the use of the death penalty. It is, however, not the strongest. The strongest argument in support of the death penalty, one that relies heavily on social science, is general deterrence.

DETERRENCE

In addition to the death penalty acting as a specific deterrent by incapacitating convicted murderers, the death penalty also acts as a general deterrent, deterring other potential murderers from committing a crime. Despite abolitionists arguing the contrary, social science research shows that the death penalty does deter others from committing murder.

In 1975, University of Buffalo Professor Isaac Ehrlich published The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment: A Question of Life and Death. This research article asserted that recent empirical investigation and analytical consideration based on econometrics models supported the view that “offenders respond to incentives” and that capital punishment and law enforcement deter crimes. Id. at 397. It claimed that during the 1950s and 1960s, “an additional execution per year . . . may have resulted, on average, in 7 or 8 fewer murders.”

In Gregg v. Georgia, the 1976 Supreme Court decision that brought back capital punishment to the federal courts, Ehrlich’s research paper was cited in an amicus brief filed by the U.S. Solicitor General. According to Professor Jeffrey Fagan, Ehrlich’s research subsequently drew sharp criticisms from social scientists and legal academics who attacked his results and announced contradictory findings. Also, in 1978, the National Academy of Sciences appointed an expert panel that severely criticized Ehrlich’s research and rejected his findings. However, according to Professor Fagan, over the next two decades, many economists and social scientists tried to reproduce or discount Ehrlich’s findings by implementing different data and statistical methods.

In 2003, researchers at Emory University concluded capital punishment had a strong deterrent effect, with each execution resulting, on average, in 18 fewer murders. The Emory researchers made this conclusion using a series of equations that incorporated county-level panel data covering the United States’ post-moratorium period. Specifically, the researchers collected data from 3,054 counties (executing and non-executing) for the period of 1977-1996. In using both county level data and post-moratorium panel data, the Emory researchers explained they were able to control for a number of observable and unobservable variables and concerns, including criminal-justice variables, demographics, aggregation, and heterogeneity. In their research, the Emory researchers also tested whether the documented deterrent effects reflected only “the overall toughness of the judicial practices in the executing states.” The research concluded, however, that tougher sentencing practices in executing states did not serve as a deterrent to murder. Rather, the deterrent effect measured in the Emory research directly correlated to the implementation of capital punishment, with each execution resulting in fewer murders.

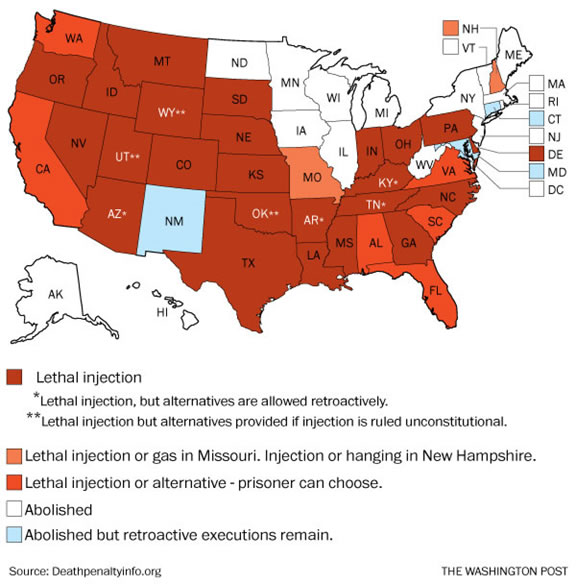

Social science comparing states that permit the death penalty with those that do not also shows that the death penalty has a general deterrent effect. Below is a map showing which states permit the death penalty:

Niraj Chokshi, Map: How Each State Chooses to Execute its Death Row Inmates, WASHINGTON POST (Apr. 30, 2014), available here.

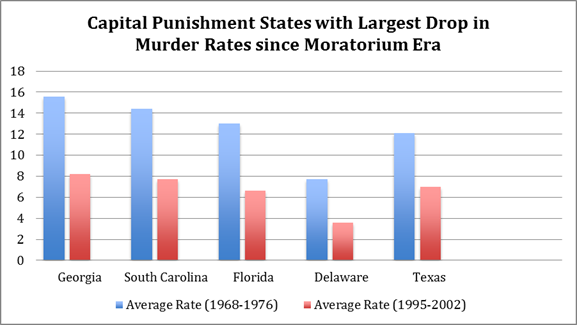

In a report prepared by Senator Orrin Hatch, Senator Hatch compared various states’ murder rates from 1968 to 1976, when there was a moratorium on the death penalty, with murder rates from 1995-2000, when the death penalty was in effect. The report showed the states with the greatest improvement in murder rates were those states that not only had the death penalty, but also aggressively applied the death penalty within its jurisdiction. Those states were: Texas, Georgia, South Carolina, Florida, and Delaware. Sen. Rep. No. 107-315, The Innocence Protection Act of 2002, 107th Cong., 2d Sess. 89 (Oct. 16, 2002). The graph below summarizes these findings:

Minority Views on the "Innocence Protection Act, available here.

Texas, for example, administered its first post-Furman execution in 1982, when its murder rate was 16.1 per 100,000—a total of 2,466 murders. By 1999, its murder rated fell to 6.1 per 100,000—a total of 1,217 murders, less than half of the 1982 figure. This has occurred despite Texas’ growing population rate. Furthermore, Harris County, where Houston is located and which has led Texas in executions, has seen Houston’s murder rate fall by 71%.

On the other hand, a number of abolitionist states have actually seen an increase in murder rates. These states include: Michigan, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Iowa, Wisconsin, West Virginia, Rhode Island, and Hawaii.

Since other studies have concluded the death penalty has no deterrent effect, social scientists continue to explore the death penalty’s deterrent effects. Nevertheless, there is at least some social science that suggests the death penalty has a specific and general deterrent effect.

THE DEATH PENALTY CASE FOR TSARNAEV

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev

Aggravating Factors in the Tsarnaev Case: In its notice of intent to seek the death penalty against Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the government identified the following statutory threshold factors and statutory and non-statutory aggravating factors:

- Statutory Threshold Factors enumerated under 18 U.S.C. § 3591(a)(2)(A)-(D): intentional killing; intentional infliction of serious bodily injury; intentional participation in acts resulting in death; and intentional engagement in acts of violence with knowledge that the acts created a grave risk of death to a person.

- Statutory Aggravating Factors enumerated under 18 U.S.C. § 3592(c): death during the commission of another crime; grave risk of death to additional persons; heinous, cruel and depraved manner of committing the offense; substantial planning and premeditation; multiple killings; and vulnerable victim.

- Non-Statutory Aggravating Factors identified under 18 U.S.C. § 3593)(a)(2): betrayal of the United States; encouragement of others to commit acts of violence and terrorism; victim impact; selection of sit for acts of terrorism; lack of remorse; status of victim; and participation in additional uncharged crimes of violence.

FUTURE DANGEROUSNESS

In addition to the aggravating factors already mentioned in the notice of intent it may be helpful for the prosecution to add future dangerousness to the list. In many punishment hearings prosecutors often call psychiatrists to testify about the defendant’s potential for future dangerousness. This procedure was questioned but then affirmed by the Supreme Court of the United States in Barefoot v. Estelle. In Barefoot two psychologists testified against the defendant, a convicted murderer, in the penalty phase and stated they felt the defendant would likely commit violent acts in the future. In the opinion of the Court Justice White wrote:

“If the likelihood of a defendant committing further crimes is a constitutionally acceptable criterion for imposing the death penalty, which it is, Jurek v. Texas, 428 U.S. 262 (1976), and if it is not impossible for even a lay person sensibly to arrive at that conclusion, it makes little sense, if any, to submit that psychiatrists, out of the entire universe of persons who might have an opinion on the issue, would know so little about the subject that they should not be permitted to testify.” |

Social scientists have conducted many studies on the predictability of future dangerousness and the topic continues to be a controversial and contested within the scientific community. One influential social scientist, Dr. Harry L. Kozol, conducted a study in 1972 to test the accuracy of psychiatrists’ predictions of dangerousness. In this study, Dr. Kozol and his colleagues followed 592 violent male offenders for 10 years. In the study, one social worker, two psychiatrists, and two psychologists at the Massachusetts Center for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dangerous Persons examined each offender. Of the 592 men in the study, 435 were released from prison. Dr. Kozol and his colleagues labeled 386 of the men as non-dangerous and 49 as dangerous.

The 5-year follow up showed that 8% of those that were predicted to not be dangerous committed a violent offense and that 34.7% of those predicted to be dangerous committed a violent offense following their release. One issue in the study’s results was the high percentage of false positives. False positives are essentially the percentage of incorrect predictions. In this study false positives were at 65.3% meaning that of the offenders psychiatrists predicted to be dangerous, 65.3% of them did not commit a violent offense upon release. However, one can still argue the predictions have some validity. This is due to the almost 35% of convicted felons who were predicted to be dangerous and did in fact commit another violent offense. Additionally, 92% of those labeled non-dangerous did not in fact commit any future crimes. As for the false positives, many believe the percentage is so high, 65.3%, not because of false predictions, but rather because many of the people committing violent behavior have not yet been caught.

YOUTH

While the prosecution will argue various aggravating factors listed above, the defense will certainly present mitigating factors to assuage the prosecution’s argument. It is likely that one of the most influential mitigating arguments from the defense will be the defendant’s age. Tsarnaev was 19 when he planted explosives at the Boston Marathon and participated in the shooting of a police officer. It is likely that the defense will argue that because Tsarnaev was only 19 that he was not fully an adult at the time of the killings, did not have the maturity level of an adult, and therefore should face a life sentence as opposed to death. However, while the science of the American Medical Association confirms that adolescents age 16 and 17 exhibit mental deficiencies that merit excluding them from the death penalty, the same is not the case for youths age 19.

In an amicus brief in Roper v. Simmons by the American Medical Association, research was cited that showed 16 and 17 year olds “do not have adult levels of judgment, impulse control, or ability to assess risk” and that the regions of their brains responsible for controlling these capacities are anatomically immature until after age 18. The American Medical Association then cited a study of over 1,000 adults and adolescents that revealed “psychosocial maturity is incomplete until age 19, at which point it plateaus.”

This research can be used to rebut the defense’s argument for mitigation due to age. Because Tsarnaev was 19, the government can argue that based on research cited by the American Medical Association, that Tsarnaev’s brain was mature and that his ability to assess risks, control his impulses, and conduct moral reasoning was not stunted because of his age.

VICTIM IMPACT STATEMENTS

Victim impact statements are often used in the sentencing phase to further show the specific harm that the defendant caused. After Payne v. Tennessee 501 U.S. 808, the Supreme Court of the United States held that the prosecution is permitted to introduce victim impact statements that provide “a quick glimpse of the life [the] petitioner chose to extinguish.” Payne overruled the part of the decision in Booth v. Maryland 482 U.S. 496 that barred victim impact testimony in the sentencing phase. However, Payne did not overrule the prohibitions Booth put on admitting “information concerning a victim’s family members’ characterization of and opinions about the crime, the defendant, and the appropriate sentence.”

It is likely that the defense will object to admitting any victim impact statements on the grounds that they would be so prejudicial as to allow emotion overwhelm reason and render the trial fundamentally unfair. However, this might be a difficult feat, as numerous similar cases, such as Timothy McVeigh’s, have generally found no constitutional error in admitting contested victim impact statements. In McVeigh’s case the government introduced 38 victim impact statements, 27 of which McVeigh objected to. The Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed McVeigh’s sentence and held that the victim impact statements did not cause the jury to find a sentence based on emotion rather than reason.

Social science research, particularly the Paternoster and Deise experiment, suggests that victim impact statements strongly influence jurors’ decision-making process in the sentencing phase. In Paternoster and Deise’s experiment they provided real case facts to a group of mock jurors and then exposed only half of the mock jurors to a real victim impact statement in the case. Of those that saw the victim impact statement, 62.5% said that they would have voted for the death penalty while only 17.5% of those that never saw the victim impact testimony said that they would vote for the death penalty. The researchers also found that in imposing a death sentence, the emotions most important to the jurors were sympathy and empathy for the murder victim. Essentially, jurors are more likely to emotionally respond to victims and recommend a death sentence after hearing victim impact testimony.

CONCLUSION

It is likely that arguing the statutory and non-statutory factors mentioned above, as well as having a forensic psychiatrist testify to Tsarnaev’s propensity for future dangerousness will give the prosecution a strong case for death. Additionally, by including victim impact statements from some of the over 260 victims and families affected by Tsarnarev’s actions and presenting social science rebutting the defense’s age mitigation argument, it is likely that the aggravating factors will substantially outweigh the mitigating factors ultimately warranting a death sentence.