For Further Study:

- Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse page containing a case overview and major filings

- A 2007 status report from the Civilian Complaint Review Board discussing increased complaints related to stops on NYCHA property

- NAACP Legal Defense Fund page for the case, featuring case updates and related filings

- Dorielle E. Obanor, Dismantling Discrimination in the Stairways and Halls of NYCHA Using Local, State, and National Civil Rights Statutes, Columbia Journal of Race and Law

Stop and Frisk and the Home: Davis v. NY and NYCHA

Compiled by Anna Barbosa, Jenna Scoville, Arielle Padover, and Jake Tucker

Introduction

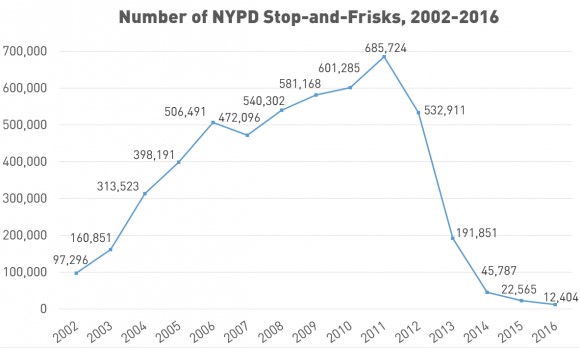

New York City residents are likely familiar with the New York Police Department’s (“NYPD”) “stop-and-frisk” policy. A “stop and frisk” is the NYPD’s practice of briefly detaining, questioning, and potentially searching an individual. The NYPD created the “stop and frisk” policy as a way to effectively detect and prevent crime. Under this practice, the NYPD stopped hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers every year.1 The NYPD’s “stop and frisk” practices have raised concerns about racism, illegal stops and an intrusion on privacy rights.

There is a long line of cases challenging the NYPD’s “stop and frisk” practices. Davis v. City of New York is one of three combined cases that argued these practices violated the constitutional rights of those stopped. The plaintiffs in Davis argued that the practices the NYPD and the New York City Housing Authority (“NYCHA”) used to enforce prohibitions against trespassing on public housing property established a widespread pattern of illegal stops, searches, and arrests of NYCHA residents and invited guests.2 The other two cases, Floyd v. City of New York and Ligon v. City of New York, challenged other aspects of the NYPD’s “stop and frisk” practices.3

In Davis, the plaintiffs used social science to show that unreasonable “stop and frisk” incidents were widespread and that the City was aware of such incidents. They also relied on social science to demonstrate that the City’s policies had a disproportionate impact based on race.

The Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees individuals protection from “unreasonable searches and seizures.”4 The Supreme Court has consistently reaffirmed that “the ultimate touchstone of the Fourth Amendment is ‘reasonableness.’” 5 In Camara v. Municipal Court of the City and County of San Francisco, the Supreme Court held that there is “no ready test for determining reasonableness other than by balancing the need to search against the invasion which the search entails.”6 A search or seizure is reasonable under the Fourth Amendment when the government’s interest outweighs the relative intrusiveness of the search or seizure.7 A year after the Supreme Court decided Camara, the Court extended the balancing test in the case Terry v. Ohio.

In Terry v. Ohio, the Supreme Court held that it is constitutional for police to stop and briefly detain an individual “for investigative purposes if the officer has a reasonable suspicion . . . that criminal activity ‘may be afoot.’”8 This kind of investigative detention, now known as a “Terry stop,” includes “stops and frisks.”

While assessing the reasonableness of the stop at issue, the Supreme Court in Terry explained the various interests at stake. The Court noted that the government had an interest in “effective crime prevention and detection,” which is enhanced by allowing an officer to detain a person for investigatory purposes even where the officer does not have probable cause.9 The Court balanced this interest against the intrusiveness of a “stop and frisk.” The Court found that such a stop can be very intrusive and has the ability to be “annoying, frightening, and perhaps humiliating.”10 After balancing these interests, the Court found that a “stop and frisk” of an individual was generally reasonable under the Fourth Amendment.

In the years since Terry both the Supreme Court and the Second Circuit have further developed the balance under the Fourth Amendment between the government’s interest and an individual’s right to be free from arbitrary intrusion by law enforcement. Specifically, the NYPD’s “stop and frisk” policy has required courts to determine how to appropriately strike the balance between individual liberty and public safety.11

Fourteenth Amendment

The Fourteenth Amendment, which was ratified in the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War, addresses a number of important civil rights.12 The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits states from denying any person equal protection of its laws.13 The equal protection clause was created to ensure that states do not draw distinctions between individuals based solely on differences that do not relate to a legitimate state goal.14 For example, it prohibits intentional discrimination on the basis of race.15 In Village of Arlington Heights v. Metro. Hous. Dev. Corp., the Supreme Court conceded that there is rarely direct proof of discriminatory intent; thus, plaintiffs can make “a sensitive inquiry into such circumstantial and direct evidence of intent as may be available.”16 The Supreme Court explained that it may be useful to start by showing that a state’s action impacts different racial groups differently because the consequences of an action can be evidence of intent.17

Facts and Procedural History

Our presentation focuses on Davis v. City of New York and NYCHA, but the case is best understood in the context of court challenges to New York City’s infamous “stop and frisk” policies.

Davis was one of three cases concurrently working their way through the federal courts in the early aughts (Floyd, Ligon, Davis). Filed in 2010, Davis specifically focused on stops that took place on public housing property owned and operated by NYCHA. Davis was initially brought by a class comprised of two non-exclusive subclasses: arrested plaintiffs and resident plaintiffs. The parties agreed to brief their motions for summary judgment in two parts. The first was adjudicated in 2012 and focused on the plaintiffs’ arrests and stops; the second was adjudicated in 2013 and focused on the defendants’ practices and policies.

Judge Shira Scheindlin of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York heard the case and granted the motions for summary judgment in part and denied them in part, before granting class certification in 2013.

The parties ultimately reached a preliminary settlement agreement in early 2015. As part of the settlement, Davis was consolidated into the court monitoring process ordered under Floyd. That monitoring process is overseen by a court-appointed monitor and incorporates input from community groups and other affected parties.

For the purposes of this analysis, we will focus on Judge Scheindlin’s March 28, 2013 decision on the parties’ motions for summary judgment. This opinion addresses the social science material used in the case.

Legal Issue

The 2013 decision focuses on whether the NYPD’s “stop and frisk” practices in and around NYCHA properties violate the Constitution, or other laws. After the first round of summary judgment briefing pared down the legal issues in question, the following issues remained: 1) arrested plaintiffs maintained Fourth Amendment, Fourteenth Amendment equal protection, NYSC article 1 sections 11 and 12, and respondeat superior claims against the City; 2) resident plaintiffs maintained Title VI, FHA, NYSHRL, NYCHRL and section 1981 claims against NYCHA.

Of these various claims, the court only addressed social science evidence in regards to the plaintiffs’ claim that the NYPD practices were unconstitutional. Here the legal issue was whether the “City displayed deliberate indifference to the constitutional rights of NYCHA residents and guests based on its failure ‘to supervise, discipline, and train its police officers to ensure lawful trespass enforcement, despite an obvious need to do so’” and whether the policies themselves were unconstitutional.

Social Science Used

Social science was used to show that the contested practices were widespread and that the City had notice of such practices. Plaintiffs presented extensive documentary and testimonial evidence. Evidence included a study by the City’s Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB) noting constant suspicionless stops in and around NYCHA buildings. The report showed that 32% of such stops were “suspicionless,” a rate three times higher than similar complaints in other locations. Plaintiffs also provided “decline to prosecute” forms (DP forms) from District Attorney’s offices showing the reason a stop took place. Lastly, Plaintiffs provided extensive testimony from residents and individuals stopped in and around NYCHA buildings.

In support of Fourteenth Amendment equal protection claims, Plaintiffs also used social science to show that the City’s policies had a disproportionate impact based on race. The bulk of social science evidence considered here took the form of Dr. Jeffrey Fagan’s expert testimony for the Plaintiff. Fagan analyzed UF-250 forms and arrest data between 2004 and 2011. UF-250 forms are otherwise known as “Stop, Question and Frisk Report Worksheets” and have to be filled out by Officers whenever a stop takes place. The City chose mostly to attack Fagan’s analysis and did not provide social science evidence showing a racially neutral purpose for its policies.

Documentary and Testimonial Evidence

1. City's Civilian Complaint Review Board (CCRB)

The CCRB became concerned about complaints that officers were stopping residents and visitors of NYCHA buildings without reasonable suspicion. In order to investigate the complaints, they conducted a study which revealed a complaint rate of 32%, nearly three times the complaint rate regarding suspicionless stops at similar locations.

The City did not contest the study’s findings or methodology. Instead, they argued that the study predated the City’s 2010 “IO 23” policy, and therefore did not reflect current police practices. The Court reserved the issue of whether the implementation of IO 23 altered police practices as a whole, noting that this was at minimum a genuine issue of material fact.

2. DP Forms and Testimony

Plaintiffs also included a sample of sixty-four decline to prosecute (DP) forms from various District Attorney’s offices. Based on the sample presented, 24 DP Forms for trespass arrests indicated that the basis for the arrest was the officer’s observation that the individual had exited a NYCHA building. The City argued that the DP Forms are hearsay because they contain written assertions from out-of-court declarants. The Court found that the DP forms were admissible under a hearsay exception.

Plaintiffs also included testimony from officers, NYCHA residents and guests that corroborated their argument that officers engaged in unconstitutional stops and arrests. The testimonial evidence was not contested.

I. Dr. Fagan's Study

1. Methodology

Dr. Fagan conducted an empirical analysis of UF-250 Forms between 2004 and 2011. A UF-250 Form, also known as a “Stop and Frisk Police Worksheet,” is a form required for an officer to complete after each Terry stop. The form contains several checkboxes intended for officers to explain the circumstances of the stop. The form also contains a “Other Reasonable Suspicion Of Criminal Activity (Specify)” or “Other” Box in which officers can check and supplement with a handwritten note.

Dr. Fagan’s analysis concluded that there were roughly 200,000 stops on suspicion of trespass in NYCHA buildings between 2004 and 2011. He used the following factors to produce multivariate regression models:

1. NYPD stop and frisk activity for trespass and other suspected crimes in NYCHA properties and surrounding areas

2. NYPD trespass arrests in NYCHA properties and surrounding areas

3. Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the places where the stops and arrests occurred (namely racial composition of NYCHA residents and guests)

4. Local crime conditions in NYCHA sites and in surrounding areas

5. Characteristics of policing in those areas

2. Findings

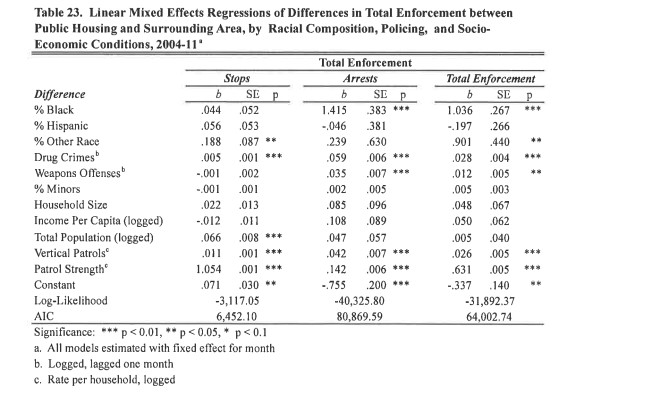

Based on the statistical analysis, Fagan concluded that there are roughly two to three more total stops and arrests in NYCHA public housing sites compared to the immediate surrounding areas, even after controlling for the other tested factors.

Fagan’s studies also concluded that for trespass enforcement and two other policy-relevant crime categories, racial and ethnic composition is a significant predictor of observed differences in enforcement patterns. Fagan found that the greater the difference in composition of Black and Latino public housing residents and the surrounding area, the greater the disparity in enforcement practices.

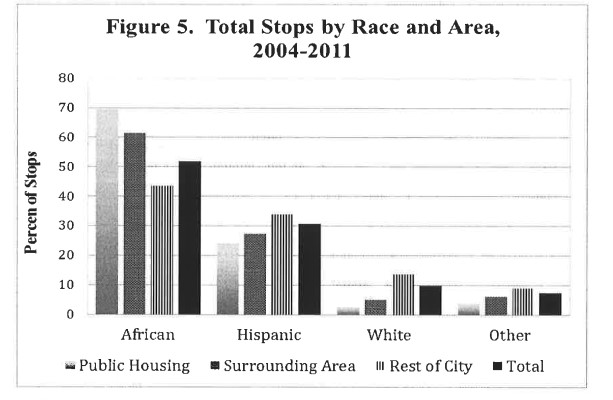

Citywide, 51.8% of persons stopped from 2004-11 were Black. In public housing, Blacks comprise 69.5% of stops, more than the citywide rate, but a smaller percentage (61.4) of the stops in the surrounding areas, Hispanics comprised 30.8% of all stops, and Whites were 9.9%. Hispanics comprised 24.2% of stops in public housing, less than the Citywide rate and Ìess than the rate in the surrounding areas. Whites were rarely stopped in public housing.

In regards to the UF-250 Forms, the “high crime” area category was checked off consistently between 60%-65% for stops across public housing developments, regardless of existing variations in actual crime rate. The “other” box was checked off in 55% of the citywide stops for suspected trespass, and even more often (65%) for trespass stops in NYCHA housing.

3. Criticism and the Court's Response

The City’s first criticism of Fagan’s study is interpretive. In its brief for summary judgment it argues that UF-250 evidence cannot be used to prove widespread unconstitutional police practice. The city cites three cases where courts have expressed criticism regarding the use of statistics to prove discriminatory intent. The cases cited regarded Fourteenth Amendment claims where plaintiffs attempted to prove discriminatory intent. Judge Scheindlin distinguished the cases cited by the City by arguing that they failed to assess the validity of statistical evidence in illustrating widespread police practice. Here, the Fagan study was narrow in its goal of assessing the relationship between race composition and enforcement practices in public housing for Fourth Amendment purposes. Moreover, Plaintiffs relied on documentary and testimonial evidence in addition to the Fagan study.

The City also made a Daubert challenge based on a previous finding in Floyd v. City of New York. In Floyd, Judge Scheindlin found that classifying UF-250 Forms as “Indeterminate” when the “Other” box was checked on side 1 of the form (regardless of what was handwritten or checked on side 2) would mislead jurors in believing that the stop was unjustified. The City argued that Fagan’s conclusions about the forms containing a checked “other” box would violate Rule 403 because “its probative value is substantially outweighed by the danger of… misleading the jury.” The judge, acting as a Daubert gatekeeper, must exclude unreliable information. Judge Scheindlin rejected the Daubert challenge, finding that Fagan’s determinations of UF-250 Forms were different from Floyd because Floyd referred to general classifications, such as “Indeterminate,” “justified” or “unjustified.”

Implications of Davis v. City of New York for New Yorkers

Davis had the potential to specifically delineate the rights that NYCHA residents and their visitors had with respect to stops on public housing property owned and operated by NYCHA, which would have affected thousands of New Yorkers, since NYCHA’s population is larger than public housing populations of most cities: over 400,000 New Yorkers live in over 330 NYCHA developments throughout the five boroughs.18 However, since the case was ultimately settled, these rights were not explicitly announced by the court.

What we do know from Judge Scheindlin’s decision on the parties’ motions for summary judgment is that those living in NYCHA housing are entitled to some degree of privacy in their homes, even if that right is not as strong as it would be in non-public housing. Like public schools and public employers, which are required to operate within constitutional limitations that wouldn’t apply in a private school or private business, security in public housing also must act within constitutional limitations that would not apply to private security in a private building.19

As the opinion says, “The NYPD may not, for example, forcibly stop and question every person who enters a NYCHA building, as a doorman in a private building is free to do.”20

Further, the preliminary settlement explicitly says that “NYCHA residents and their authorized visitors have the same legal rights as the residents and authorized visitors of any other residential building in New York City.”21 Therefore, even though the settlement is not necessarily equivalent to a formal court decision for purposes of precedent, the court has to approve the settlement, so it is possible that the right to privacy in NYCHA housing actually could be argued to be as strong as it would be in non-public housing.

Implications of the Social Science about Stop and Frisk

In protecting people from unreasonable searches and seizures, the Fourth Amendment requires balancing between the public interest in public safety and an individual’s right to personal security free from arbitrary interference by law officers. The social science used in Davis (Dr. Fagan’s statistical analysis of UF-250 forms and arrest data) showed that those living in NYCHA housing are often not free from arbitrary interference to an extent that seems excessive when balancing it against the public interest in public safety, and thus that “the City has engaged in a practice of making unconstitutional stops and arrests in and around NYCHA buildings as part of its trespass enforcement practices.”22

Despite the City’s criticisms of Dr. Fagan’s study, Judge Scheindlin denied the City’s motion for partial summary judgment on the widespread practice claim, holding that “a reasonable juror could find that the constitutional injuries suffered by named plaintiffs are the same injuries quantified by Dr. Fagan's report” and that “‘it would be an injustice to prevent the jury from hearing about the extremely rich and informative material’ contained in the UF-250 database.”23 Judge Scheindlin’s acceptance of this study is important because it suggests the possible acceptability of the use of this type of social science research in other stop-and-frisk cases in New York and potentially elsewhere.

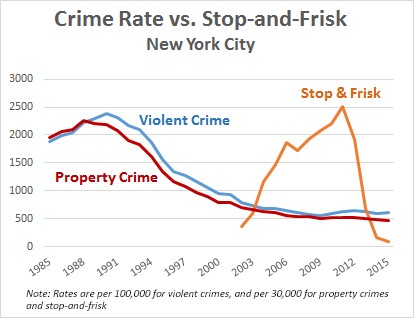

Additionally, statistics show that there is apparently no relationship between crime and stop-and-frisk: data collected shows that property crime and violent crime in New York both consistently fell over time, despite the fact that the number of stops both increased and decreased during the same time period. This lack of correlation may suggest that stop-and-frisks as a police tactic may be a waste of time and resources.

Post-Davis: Effects of Changes to Stop-and-Frisk and Effects of the Monitoring Program

Under the preliminary settlement, Davis was consolidated into the court monitoring process ordered under Floyd. In addition, the settlement revised the NYPD patrol guide and related training materials for security in NYCHA housing, imposes a documentation requirement for arrests for trespassing in NYCHA housing, and modifies certain NYCHA rules for residents.25

While statistics show that the number of stop-and-frisks generally have decreased in the years since the monitor program was put in place and since the preliminary settlement was announced, the stops had been steadily decreasing since before the program was put in place, so the effects of the program and the changes to the NYPD patrol guide/training materials on the number of stops are not immediately clear.26

In November 2017, the monitor wrote a report in which he noted that NYPD officers found the new policies governing stops to be “unrealistic and confusing” and found the Civilian Complaint Review Board hearings related to complaints about stops to be “unfair and harsh.”27 Additionally, the report noted that NYPD officers “express fear about doing the stops . . . based on a concern that if they do their jobs, they do stops, and people file complaints, the Department won't have their backs.”28 This shows that, even if the implementation of the program did have the effect of decreasing the number of stops, it is not clear that the additional training and new rules are the reason for the decrease.

Further, despite the decrease in the number of stops, a majority of those stopped in recent years continued to be “totally innocent” (80% in 2015, 76% in 2016, 66% in 2017), and a disproportionate percentage of those stopped were still black and Latino.29 These statistics support the possibility the new training and new policies do not solve all the relevant issues: although the actual number of stops in New York have decreased, the underlying issues of racial bias clearly remain present.

Footnote Resources:

1 The NYPD stopped hundreds of thousands of individuals up until the end of 2013. After Davis, Floyd, and Ligon were decided, the number of “stop and frisks” decreased dramatically. Stop and Frisk Data, NYCLU (last visited Mar. 21, 2018).

3 The plaintiffs in Floyd argued the NYPD’s “stop and frisk” practices on public streets violated the Constitution. The plaintiffs in Ligon challenged the NYPD’s enforcement of Operation Clean Halls, which allowed the NYPD to patrol private apartment complexes.

5 Brigham City, Utah v. Stuart, 547 U.S. 298, 403 (2006).

6 Camara v. Municipal Court of the City and Cnty. Of S.F., 387 U.S. 523, 536–37 (1967).

8 Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968); United States v. Swindle, 407 F.3d 562, 566 (2d Cir. 2005) (quoting United States v. Sokolow, 490 U.S. 1, 7 (1989).

11 See Davis v. City of New York, 902 F. Supp. 2d 405, 408 (S.D.N.Y 2012).

14 Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 239 (1976).

17 Id.; see also Pers. Admin. v. Feeney, 442 U.S. at 279, n.24 (1979), Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 242 (1976) (explaining that “an invidious discriminatory purpose may often be inferred from the totality of the relevant facts, including the fact, if it is true, that the [practice] bears more heavily on one race than another.”)

18 Stop and Frisk in Public Housing.

21 Preliminary Settlement Reached in Federal Class Action Lawsuit.

24 The facts about stop-and-frisk in New York City.

25 Preliminary Settlement Reached in Federal Class Action Lawsuit.

27 NYPD cops 'express fear' of carrying out stop-and-frisks in testing phase of new training, monitor reports.

28 NYPD cops 'express fear' of carrying out stop-and-frisks in testing phase of new training, monitor reports.