Neurological Evidence and Battered Woman Syndrome

Compiled by Taylor Davis, Tyler Hepner, and Ashlee Riner

Development of Battered Woman Syndrome

Battered Woman Syndrome (BWS) is controversial in courtrooms, but has come a long way since Dr. Lenore Walker first described the phenomena in 1979. In her book, The Battered Woman, Walker describes the Cycle Theory and its three stages of battering that may result in BWS. Her theory took into account the time between battering events and when women finally acted in self-defense:

1. Tension building phase – build up of minor abusive incidents (emotional threats, verbal outbursts) in which the woman is hyper-vigilant to her spouse’s cues and changes her behavior accordingly

2. Acute battering incident- severe or lethally violent battering incident

3. Loving contrition- batterer is remorseful and charming and promises never to harm the woman again

Walker’s theory answered the conundrum that was presented in cases of women waiting extended periods of time before acting in self-defense by killing their batterer. The imminence of the threat under the traditional approach to self-defense seemingly barred suffers of BWS from claiming self-defense when they killed their batterer, especially when the batterer was sleeping.

In order to allow this evidence into court, jurisdictions have developed numerous standards. One of the first standards comes from Dyas v. United States. The three-pronged test supplied by Dyas is as follows:

1. The testimony’s subject matter "must be so distinctly related to some science, profession, business or occupation as to be beyond the ken of the average layman."

2. "The witness [must] have sufficient skill, knowledge, or experience in that field or calling as to make it appear that his opinion or inference will probably aid the trier in his search for truth."

3. Expert testimony is inadmissible if "the state of the pertinent art or scientific knowledge does not permit a reasonable opinion to be asserted even by an expert."

The focus of the test is relevance and specialization. If a layperson is able to understand BWS then expert testimony regarding BWS is not needed and the expert will be barred from testifying. Many jurisdictions use this reasoning to limit the role of experts in BWS cases.

For a more generalized discussion of BWS please refer to: Battered Woman Syndrome

DSM-V

Battered woman syndrome falls under the umbrella of post-traumatic stress disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. While BWS is not its own diagnosis, the DSM does recognize problems such as rape and intimate partner violence in highlighting the gender-based differences in diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. Within its description of PTSD’s risks, consequences, factors, and issues, the DSM includes a paragraph discussing the gender-related diagnostic issues with PTSD.

| “PTSD is more prevalent among females than among males across the lifespan. Females in the general population experience PTSD for a longer duration than do males. At least some of the increased risk for PTSD in females appears to be attributable to a greater likelihood of exposure to traumatic events, such as rape, and other forms of interpersonal violence.” |

AM. PSYCHIATRIC ASS'N, DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL OF MENTAL DISORDERS (5th ed. 2013).

Neurological Evidence

For decades, women have been subjected to abuse at the hands of individuals who claimed to care for them. Many victims of domestic abuse have attempted to utilize a defense popularly known as battered woman syndrome. The legal system being what it is, it has been difficult to gain justice through this defense alone. Scholars are now proffering that neurological evidence may help to bolster some of these devastating cases.

In fact, Arias and Pape’s study of sheltered battered women found that “psychological abuse contributed unique variance to battered women’s post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms.” Further, a study by Sackett and Saunders compared 30 sheltered battered women with 30 non-sheltered battered women to assess the intensity of their “depression, self-esteem, and fear.” The study found that psychological abuse contributed to increasing all three elements in both groups, but significantly in non-sheltered women.

In addition, L.L. Marshall’s study found that “psychological abuse added unique variance to the prediction of women’s stress, distress, self-esteem, depression, and health quality of life,” which also controlled for the consequences of physical and sexual aggression.

Still, as we know from studying Daubert and Frye, the mere existence of evidence is usually not enough to give a shaky defense Herculean strength in a court of law. However, there is also a large amount of evidence acknowledging PTSD as a major cause of loss of ability to determine whether an individual is operating in a past or a present experience. More succinctly put, PTSD causes a shrinking on the hippocampus and drastically changes the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Both of these effects leave individuals with triggers for “extreme stress responses,” especially when presented with specific and familiar stimuli.

This evidence can surely be proffered in a battered woman’s syndrome case as evidence that a battered woman is suffering from PTSD, which causes changes to her neurological functions, which could explain the reason why she may have attacked an individual who has battered her in the past but was not battering her at the time of her attack. The argument still needs further research but the initial groundwork is certainly present and waiting to be utilized in the courtroom.

Frye v. Daubert Jurisdictional Challenges

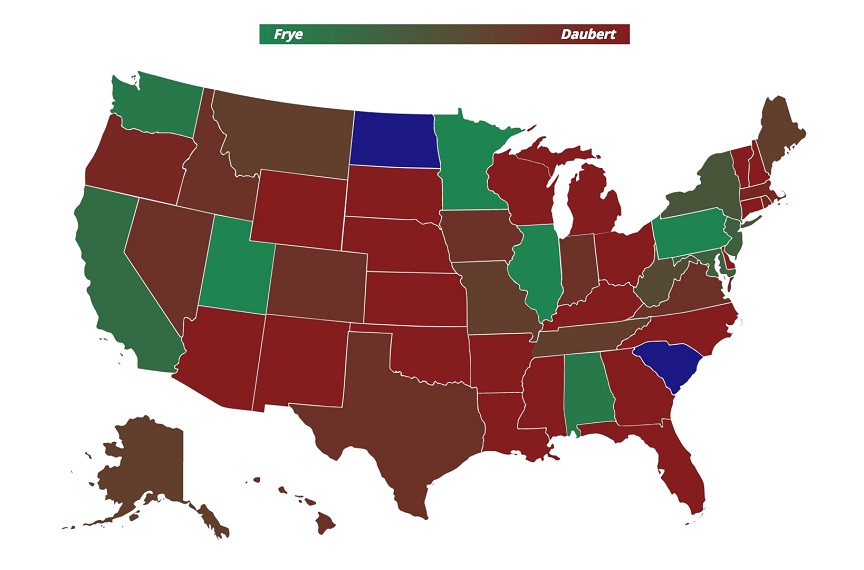

There are two major competing doctrines that govern the admissibility of expert scientific testimony in the United States. The Frye Test predates the Daubert Standard and was previously the majority doctrine but now has been displaced. The Frye Test, also known as the general acceptance test, comes from Frye v. United States, and instructs the court to admit expert scientific testimony when the testimony will be about something that has become generally accepted by the relevant scientific community as reliable. The Frye test is widely regarded as more stringent than the Daubert Standard, but a few jurisdictions have held the opposite to be true so there is not a complete consensus.

*North Dakota and South Carolina have developed standards that differ from both Frye and Daubert to a significant degree.

**Source

In contrast to the Frye Test, the Daubert Standard is broader in the scope of the task presented to judges who are not experts themselves with respect to scientific evidence. The Daubert Standard is the result of the Daubert Trilogy and requires judges to balance four questions when acting as gatekeeper for expert scientific evidence:

1. Whether the theory or technique can be and has been tested;

2. Whether the theory or technique has been subjected to peer-review and publication;

3. Whether the theory or technique has a known or potential error rate;

4. Whether the theory or technique has general acceptance within a relevant scientific community.

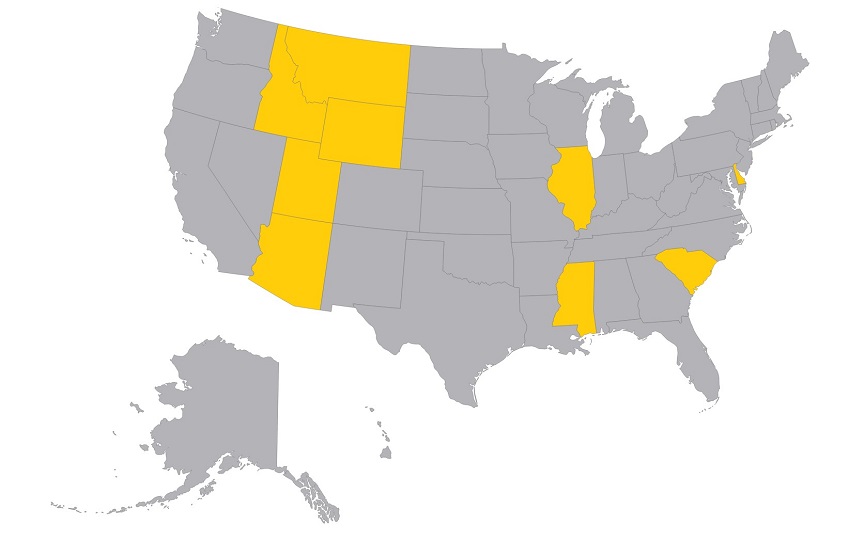

The opposing Frye Test and Daubert Standards do not result in jurisdictions that are either more or less opposed to expert testimony for BWS. The highlighted yellow states below are the jurisdictions in which expert testimony is disallowed in BWS cases. Broken down: 6 Daubert Standard jurisdictions, 2 Frye Test jurisdictions, and 1 miscellaneous jurisdiction forbid expert testimony in DWS cases. Alternatively 15% of Daubert Standard jurisdictions forbid expert testimony compared to 24% of Frye Test jurisdictions.

The difference between the two doctrines do not account for the difference in admissibility however. The states that forbid expert testimony do so because of relevance and not because of the two doctrines. For example, Mississippi has never outright banned the testimony of an expert witness in BWS cases. However, they have held that an expert would likely never be necessary in such a case because their Supreme Court believes that understanding why a woman does not leave a man who abuses her is within the capabilities of a layperson to comprehend. Lentz v. State, 604 So.2d 243.

Case Law

In many cases where expert testimony about battered woman syndrome is admitted it is used to support a claim of self-defense when a victim has attacked her abuser. In recent years, however, it has begun to expand its reach and has been applied in other contexts.

Nicole Brewington’s boyfriend Kashon Scott frequently physically abused Ms. Brewington and her three children. On May 29, 2007, Ms. Brewington’s three-year-old son died as a result of beatings he received at the hands of Mr. Scott. Mr. Scott faced charges for the child’s death, but Ms. Brewington was also charged with the aggravated manslaughter of a child. Ms. Brewington’s other children testified that they told their mother Mr. Scott was beating their younger brother, who showed signs of serious physical injury, but Ms. Brewington failed to seek medical care for the child.

At trial Ms. Brewington sought to admit evidence that she suffered from battered woman syndrome which caused her not to realize Mr. Scott was beating her son or that the child needed medical attention. Once she realized, Ms. Brewington claimed that Mr. Scott took away her cellphone which prevented her from calling for help. Ms. Brewington sought to use the BWS evidence to negate the mens rea element (culpable negligence) in her case.

Florida used the Frye Test to determine the admissibility of expert evidence (subsequently the state legislature has adopted the Daubert Standard). The trial court noted that evidence of BWS had passed the Frye test and been admitted in cases to explain the aggressive acts of an abuse victim who claimed self-defense. In its opinion, the court pointed to several other jurisdictions that had admitted BWS evidence in contexts other than self-defense:

Porter v. State, in which the Court of Appeals of Georgia allowed BWS expert testimony in the case of a psychologist who said the defendant was unaware, as a matter of impaired perception, of the fact that her husband was abusing her son.

Mott v. Stewart, in which the United States District Court for the District of Arizona allowed BWS expert testimony intended to show that the defendant did not act intentionally or knowingly in failing to protect or seek medical care for her child who was abused by her boyfriend.

Pickle v. State, in which the Court of Appeals of Georgia held that expert testimony about BWS was admissible to negate a showing of criminal intent in defendant’s abuse of her children.

State v. Stewart, the Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia allowed a defendant accused of murdering her husband to introduce BWS expert testimony, not in a claim of self-defense, but to attempt to negate elements such as premeditation, malice, or intent.

Arcoren v. United States, Trujillo v. State, People v. Lafferty, People v. Brown, and State v. Haines, in which the Eighth Circuit, Supreme Court of Wyoming, Colorado Supreme Court, Supreme Court of California, and Supreme Court of Ohio upheld the admission of expert evidence regarding BWS to explain victims’ recantations of testimony about incidents of abuse in criminal cases against their abusers.

Ms. Brewington sought to expand the reach of BWS, but the trial court ruled that the evidence was inadmissible because it had not been studied and generally accepted in the context of failing to protect a child from abuse. Although the appellate court held that Ms. Brewington’s evidence was inadmissible under the Frye standard, the court noted that this area of law “beckons for further analysis in the scientific and legal community.”