For Further Study:

- Fillmore Buckner & Marvin Firestone, "Where the Public Peril Begins" 25 Years After Tarasoff, 21 J. LEGAL MED. 187 (2000)

- John G. Fleming & Bruce Maximov, The Patient or His Victim: The Therapist's Dilemma, 62 CAL.L.REV. 1025 (1974)

- People v. Burnick, 14 Cal.3d 306 (1975) (holding that the future dangerousness of mentally disordered sex offenders must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt before they can be committed or recommitted to the State Department of Health under the California mentally disordered sex offender laws).

- Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California, 17 Cal. 3d 425 (1976)

- Thompson V. County of Alameda, 27 Cal.3d 741 (1980)

- Peter H. Schuck & Daniel Givelber, Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California: The Therapistís Dilemma, in Torts Stories (Robert L. Rabin & Stephen Sugarman eds., 2003).

- Bernard L. Diamond, The Psychiatric Prediction of Dangerousness, 123 U. Pa. L. Rev. (1974).

- Alan A. Stone, The Tarasoff Decisions: Suing Psychotherapists to Safeguard Society, 90 Harv. L. Rev. 358 (1976).

- Toni Pryor Wise, Where the Public Peril Begins: A Survey of Psychotherapists to Determine the Effects of Tarasoff, 31 STAN. L. REV. 165 (1978).

- William J. Bowers et al., How Did Tarasoff Affect Clinical Practice?, 484 ANNALS, AAPSS 70 (1986).

- APA, Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (Aug. 21, 2002)

The Impact of Social Science Evidence in Predicting Dangerousness and Establishing a Duty to Warn

Compiled by Matt Campbell and Cristina Quinones-Betancourt

General Overview of Duty to Rescue

Generally, American tort law does not impose liability on parties for failing to aid or rescue other parties. The Restatement (Second) of Torts § 314 (1965) states: "The fact that the actor realizes or should realize that action on his part is necessary for another's aid or protection does not of itself impose upon him a duty to take such action." However, the law provides narrow exceptions in some instances when parties owe a specific duty to one another, such as when parties have a "special relationship."

Special Relationships

Special relationships apply to narrow categories of relationships.

Figure 2: Special Relationships

Under modern tort law, "special relationships" usually refer to those involving dependence or mutual dependence, such as therapist-patient relationships (See Restatement (Second) of Torts § 315)).

Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California

On October 27, 1969, University of California, Berkeley graduate student Prosenjit Poddar sought out Berkeley student Tatiana Tarasoff while she was alone in her home, shot her with a pellet gun, chased her into the street with a kitchen knife, and stabbed her seventeen times, causing her death.

|

|

Podder became enamored with Tatiana Tarasoff and was confused and enraged when she rejected his advances. On June 5, 1969, Poddar sought and received emergency psychological treatment from Dr. Lawrence Moore, a psychologist employed by the Cowell Memorial Hospital at the University of California at Berkeley.

Figure 5: Cowell Memorial Hospital

Poddar saw Dr. Moore seven times. On August 20, 1969, during his 7th therapy session, Poddar confessed that he planned to kill Tatiana Tarasoff. Dr. Moore diagnosed Poddar with having an acute and severe "paranoid schizophrenic reaction." He and two other doctors determined that Poddar should be committed to a psychiatric hospital for observation and contacted the police.

However, the police only briefly detained Poddar, releasing him after he promised to stay away from Tarasoff. Following Poddar’s release, Dr. Harvey Powelson, Dr. Moore’s superior, instructed the police to return the letter from Dr. Moore instructing them to detain Poddar, ordered that the letter and all notes taken on Poddar be destroyed, and instructed Dr. Moore to take no further action in detaining Poddar. The doctors who examined Poddar never notified Tarasoff or her family about Poddar’s threatening statements. Poddar never returned to therapy and killed Tatiana Tarasoff as planned.

People v. Poddar: Poddar's Criminal Trial

At his criminal trial, Poddar pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. Psychologists who evaluated Poddar prior to the murder presented evidence at the trial demonstrating that Poddar lacked a culpable mental state at the time of the murder because he was insane and a paranoid schizophrenic.

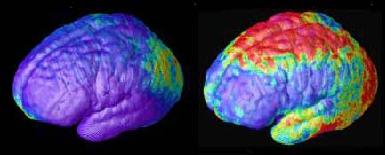

Figure 6: Normal Brain (left) Schizophrenic Brain (right)

Although the trial court convicted Poddar of second-degree murder, the Court of Appeal reduced the crime to manslaughter. On appeal, the California Supreme Court determined that even the charge of manslaughter was too harsh under the circumstances and reversed the conviction. Poddar was never retried and was allowed to return to India, where he reportedly married a lawyer and led a normal life.

Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California (Tarasoff II)

Following Poddar’s criminal trial, Tarasoff’s parents sued the psychiatrists and police who were involved in treating Poddar. The charges against the police were ultimately dropped because the police were immune to the suit.

Although the trial court and California Court of Appeal determined that Tarasoff’s parents had no cause of action, the California allowed Tarasoff’s parents to amend their complaint to state the following:

| "[R]egardless of the therapists' unsuccessful attempt to confine Poddar, since they knew that Poddar was at large and dangerous, their failure to warn Tatiana or others likely to apprise her of the danger constituted a breach of the therapists' duty to exercise reasonable care to protect Tatiana." |

The California Supreme Court ultimately reversed and remanded the Court of Appeal’s decision. In its holding, the California Supreme Court considered the following factors:

- Foreseeability of harm to Plaintiff;

- the degree of certainty that Plaintiff suffered injury;

- the closeness of the connection between Defendent's conduct and the injury suffered by Plaintiff;

- the moral blame attached to Defendent's conduct;

- the policy of preventing future harm;

- the extent of the burden to Defendent and consequences to the community of imposing a duty to exercise care with resulting liability for breach;

- and the availability, cost and prevalence of insurance for the risk involved.

Of these factors, the California Supreme Court held that foreseeability was most important when establishing a duty because a defendant generally owes a duty of care to all persons endangered by his or her conduct, with respect to all risks that make the conduct unreasonably dangerous. Moreover, when the avoidance of foreseeable harm requires a defendant to control or warn about the conduct of another person, a defendant is generally liable only if the defendant had a special relationship with the dangerous person or to the potential victim. Since the relationship between a therapist and the patient constitutes a special relationship, the Court determined that the defendant-therapists had a duty to use reasonable care to protect Tatiana Tarasoff and breached that duty.

The Tarasoff Rule

"When a therapist determines, or pursuant to the standards of his profession, should determine, that his patient presents a serious danger of violence to another, he incurs an obligation to use reasonable care to protect the intended victim against such danger."

"[T]he judgment of the therapist in diagnosing emotional disorders and in predicting whether a patient presents a serious danger of violence is comparable to the judgment which doctors and professionals must regularly render under accepted rules of responsibility."

In other words, The Court also rejected as "entirely speculative" the defendant-therapists' predictions that imposing a duty to warn on therapists would deter some violent patients from seeking counseling and would disrupt the treatment of other patients. Moreover, the Court concluded that the claim that psychiatric patients could be harmed if their therapist warned their potential victims was "uncertain and conjectural."

Social Science Evidence: The Difficulties of Predicting Dangerousness

In Tarasoff, the defendant-therapists urged the Court to consider evidence demonstrating that predictions of future dangerousness are inherently unreliable. The evidence presented by the defendants was admissible under the following admissibility tests:

- Frye General Acceptance Test: This test states that scientific evidence may be admitted if it is both relevant to the case at bar and is generally accepted as true by the scientific community.

- Daubert Sound Methodology Test: This test requires that the scientific evidence be relevant and that it reflect good science derived through sound methodology. Factors that may indicate whether a piece of scientific evidence meets this test include: demonstrable error rates, testing, peer-review, and general acceptance in the scientific community.

- Federal Rule of Evidence 702:

"If scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will assist the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue, a witness qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education, may testify thereto in the form of an opinion or otherwise, if (1) the testimony is based upon sufficient facts or data, (2) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods, and (3) the witness has applied the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case."

The defendant-therapists argued that the imposition of a duty to exercise reasonable care to protect third persons was impractical because therapists could not accurately predict whether or not a patient would resort to violence.

The American Psychiatric Association ("APA") and other organizations agreed, arguing that imposing a duty to warn on therapists would:

- Cause therapists to over predict violence;

- make providers reluctant to treat dangerous patients;

- make violent patients less likely to seek treatment; and

- diminish the effectiveness of treatments

The California Supreme Court cited to Dr. Bernard Diamond’s 1974 article, Psychiatric Predictions of Dangerousness, in which he argues that dangerousness cannot be reliably predicted. Diamond’s article referred to several recent studies:

- A study by Dr. Carl P. Malmquist, in which he determined that warning signs and symptoms typically found in violent offenders are also commonly found in people who never commit a violent act

- Another study followed 967 patients who had previously been confined in a hospital for the criminally insane and were transferred to ordinary civil mental health hospitals after the Supreme Court ruled that their continued confinement violated the Equal Protection Clause. Only twenty-six patients committed acts serious enough to warrant their return to a maximum-security hospital for the criminally insane.

- Other studies demonstrate that conditions most clearly recognized as mental illness, such as schizophrenia and the other psychoses, are not found significantly more often in the criminal population.

Although it agreed with the defendants’ evidence, the Tarasoff Court ultimately held that Poddar’s psychiatrists were liable for failure to warn (also referred to in this case as "failure to protect").

The claimants brought a wrongful death action against the County of Alameda following their release of James F., a juvenile offender. The claimants alleged that James F. knew that he had "latent, extremely dangerous and violent propensities regarding young children and that sexual assaults upon young children and violence connected therewith were a likely result of releasing [him] into the community." The claimants also maintained that James F. had stated that he would kill a neighborhood child if released. Despite this threat, the county temporarily released James F. into his mother’s custody without warning local police or nearby families. Almost immediately, James F. sexually assaulted and murdered the claimant’s five year-old son.

After noting that the county has discretionary authority to release James and disposing of other minor matters, the Court held that the County did not have a duty to warn the community prior to the release. The Court found that parole and probation decisions do not encourage open dialogue in the same way as psychiatrist-patient relationships. The Court also noted that parole decisions are imprecise and cited to a study showing that that nearly 18% of parolees nationwide violate their probation before they have served their terms. Since the County functions as an arm of the public, the Court held that the public at large bears the cost of failed rehabilitation.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court of California held that the county was immune from suit under Cal. Gov’t Code Section: 820.2, because the decision not to warn was a matter of discretion. Moreover, the County also had immunity under Cal. Gov’t Code Section: 845.8(a), which grants immunity to decisions regarding the release of a prisoner

Explaining the Verdicts

At the time when Tarasoff and Thompson were being decided, courts were moving from corrective justice to a more "functional ideal" in which the courts were "risk regulators." This functionalism enlarged the scope of tort liability in favor of furthering policy goals, such as allocation of risk.

The California Supreme Court has held that foreseeability is most important factor when establishing a duty because a defendant generally owes a duty of care to all persons endangered by his conduct. When the avoidance of foreseeable harm requires a defendant to control or warn about the conduct of another person, a defendant is generally liable only if the defendant had a special relationship with the dangerous person or to the potential victim. Since the relationship between a therapist and his patient is a special relationship, the Court determined that the defendants in Tarasoff had a duty to use reasonable care to protect Tatiana Tarasoff. Moreover, since the County in Thompson did not have a special relationship with the claimants, it was under no obligation to warn them about John F.’s release.

Legislative Impact

In California, a psychiatrist’s duty to warn is now labeled as a duty to protect:

California Code § 43.92 (as Amended in 2012)

Psychotherapists; duty to warn of threatened violent behavior of patient; immunity from monetary liability

(a) There shall be no monetary liability on the part of, and no cause of action shall arise against, any person who is a psychotherapist as defined in Section 1010 of the Evidence Code in failing to protect from a patient's threatened violent behavior or failing to predict and protect from a patient's violent behavior except if the patient has communicated to the psychotherapist a serious threat of physical violence against a reasonably identifiable victim or victims.

(b) There shall be no monetary liability on the part of, and no cause of action shall arise against, a psychotherapist who, under the limited circumstances specified in subdivision (a), discharges his or her duty to protect by making reasonable efforts to communicate the threat to the victim or victims and to a law enforcement agency.

Impact on Mental Health Professionals

- The number of therapists warning potential victims have doubled

- Therapists are more likely to take more careful and deliberate steps to determine patient dangerousness

- Therapists have a greater awareness of the violent patient's potential for acting out and use closer scrutiny and better documentation when treating their patients

- Psychiatrists are now more careful to inform patients at the outset of treatment regarding the limits of their confidentiality

- Studies demonstrate that Tarasoff did not have disastrous results on patients-psychiatrist confidentiality as originally predicted (See Fillmore Buckner & Marvin Firestone, "Where the Public Peril Begins" 25 Years After Tarasoff, 21 J. LEGAL MED. 187 (2000)).

How Psychiatrists Evaluate Patients Today

While psychiatrists still use evaluative tools, such as scales, to diagnose and treat patients, the APA Practice Guide states that these types of evaluative tools are not all-inclusive. Specifically, the guidelines state:

| "[R]ating scales should never be used alone to establish a diagnosis or clinical treatment plan; they can augment but not supplant the clinician's evaluation, narrative, and clinical judgment." |

Psychiatrists use mental status examinations to determine whether patients pose a threat to themselves or others. This type of examination typically contains the following elements:

(1) Appearance and general behavior

(2) Motor activity

(3) Speech

(4) Mood and affect

(5) Thought processes

(6) Thought content

(7) Perceptual disturbances

(8) Sensorium and cognition

(9) Insight

(10) Judgment

Currently the APA maintains that:

| "[A psychiatristís] default position is to maintain confidentiality unless the patient gives consent to a specific intervention or Communication. However, the psychiatrist is justified in attenuating confidentiality to the extent needed to address the safety of the patient and others." |

Conclusion

Despite the decades since the Tarasoff and Thompson decisions, psychiatrists today are still unable to accurately predict the dangerousness of psychiatric patients. Thus, in cases where a defendant’s duty to warn may stem from a third party’s potential dangerousness, courts will need to continue to determine liability by weighing important policy interests against the risks posed by potentially dangerous persons instead of purely relying on psychiatrists’ predictions of dangerousness.