For Further Study:

- Christopher Slobogin, RISK ASSESSMENT

- For the use of preventive detention in Germany

- Racial profiling in the U.S. Driving While Black

A Comparative Analysis on Risk Assessment

Compiled by Mathias Kahler, Shir Lachish, and Catarina Tourais

Introduction

One of a state’s justifying main functions is the protection of its citizens against threats resulting from other citizens or external sources. However, an exclusion of all risks threatening the citizens is not feasible since a state’s resources are inherently limited. Additionally, a state will be confined in its actions against existing hazards by legal limitations in order to protect its citizens' fundamental freedom. This leads to the finding that a state has to balance interests when it drafts and implements protective measures against risks. In this process of balancing, it is necessary for the state to assess the risks existing – the likelihood of realization of risks as well as the possible damage by such an event. Therefore, risk assessment can best be described as a universal concept in idea, directly linked with statehood as such. This does not mean, however, that its realization would be uniform in all societies.

This simultaneity of the concept’s shared core idea and differences in detail are mirrored by the history and meaning of the word "risk" as such. The word "risk is similar in a wide variety of languages/countries. It came from the Latin resicum, risicum, riscus - cliff, récif, Felsklippe, though many claim that this Latin word comes from a Greek navigation term rhizikon, rhiza which meant "root, stone, cut of the firm land" and was a metaphor for "difficulty to avoid in the sea".

One aspect of risk assessment is estimating the likelihood of being involved in a crime. Risk assessment is very similar to prediction of dangerousness but according to Christopher Slobogin in the article "Risk Assessment": ""Dangerousness" determinations are usually meant to address the binary issue of whether a person will reoffend, while risk assessments are designed to identify the circumstances under which a person is most likely and least likely to reoffend, the probability that reoffending will occur, and the type of reoffending that is risked."

In his article Slobogin specify three types of Current risk assessment techniques:

- Unstructured clinical assessment Ė "depends upon the evaluator to determine the relevant risk and protective factors, it's inconsistent among evaluators and can even vary with the same one. Evaluator focuses on the precise risk and protective factors that are associated with previous antisocial behavior by the individual in question. This type of evaluation is somewhat more structured, but because it relies on the nuances of the offender's crimes it cannot be called standardized."

- Actuarial assessment Ė "rely on empirical discovery of factors associated with recidivism, which are then weighted and combined according to an algorithm that produces recidivism probability estimates." [The example given in class about the RRASOR/Static 99 belongs to this kind of risk assessment].

- Structured professional judgment - "clinical rather than actuarial in nature, but much more structured than traditional clinical techniques. The primary goal of this type of instrument is to provide information relevant to needs assessment and a risk management plan rather than to predict antisocial behavior. Adjusted actuarial risk assessment, is to use an actuarial device to establish a base rate but then to adjust the probability estimate through consideration of other variables. Because these adjustments are not part of the algorithm associated with the actuarial instrument,the resulting judgment cannot be called actuarial."

In the scientific community, there is broad consensus that actuarial assessment and structured professional assessment tend to be significantly more reliable than unstructured clinical risk assessment. As we will demonstrate, different legal systems have different tendencies in the use of these types of risk assessment.

Racial profiling

Profiling is the use of statistical data about a group of people most likely to be presently committing a crime. Suspicion that an individual is currently involved in an offense is due to his or her membership in a certain group perceived as risk-intense. Profiling focuses on present behavior; risk assessment on future behavior.

Our project will relate to a comparative look at racial profiling, which can be defined as the use of racial or ethnic factors in the determination of profiling groups.

Israel

The Supreme Court in HCJ 4797/07 Association for Civil Rights in Israel v. the Airport Authority

The facts:

In regards to racial profiling Israel does not deny the use of ethnicity in profiling, unlike the US. According to the state, the standard of the security check is determined according to different characteristics of the passengers, those characteristics have been shown to be relevant to evaluate the potential of danger from the passengers, according to rational statistical analysis. The characteristics themselves are classified. Israeli Arabs felt discriminated in the current criteria.

The Supreme Courtis concerned about the option of ethnic profiling but also acknowledges the importance of thorough security checks. The case was not decided because of changes taking place by the airport authority in the examination process, changes meant to reduce the discrimination the Israeli Arabs feel today in the airport. the exact nature of these changes were not specified.

In this case no social science evidence was submitted. The factors of the profiling are confidential. Social science could have been used to assess the effectiveness of the profiling on the relevant population. Unlike criminal cases, in preventing terror the effectiveness of the profiling for terrorists is hard to measure, because of the low percentage of persons having terroristic intentions.

Spain

Racial profiling became a major issue in discussions about the practices of the Spanish police in the 1990s. Many people of ethnic minorities had already been complaining about discriminating treatment by the Spanish police when in 1992 a case on racial profiling started to wind its way through the courts.

The facts:

In 1992 Ms. Rosalind Williams, a Spanish citizen of black skin color was subjected to a police control:

"In the afternoon of December 6, 1992, Rosalind Williams arrived at the Valladolid Campo Grande railway station on a train coming from Madrid. She was with her husband, Federico Augustín Calabuig, and their son Ivan Calabuig-Paris. Moments after they disembarked from the train, a National Police (Policia Nacional) officer approached Williams and asked her to produce her identity document (the Documento Nacional de Identificación or DNI). The police officer did not ask her husband, son, or any other passengers on the platform for their identity documents. Williams and her husband asked the reason for the identity check. The officer replied that he was obligated to check the identity of persons who "looked like her," adding that "many of them are illegal immigrants." He went on to explain that in carrying out the identity check, he was obeying an order of the Ministry of the Interior that called on National Police officers to conduct identity checks, in particular, of "persons of color." Williams produced her identity document, and took the number of his badge."

(Case summary of the open justice initiative)

The Case in the Spanish Courts:

Ms. Williams appealed against the police actions in the Spanish courts and her case eventually came before the Spanish Constitutional Court. The Constitutional Court declined to enter into an evaluation of general policies of racial discrimination in Spain. It concluded on the one hand, that no general discriminatory policy was established, while on the other hand the inclusion of racial or ethnic factors in police profiles to search for illegal immigrants was not unconstitutional under the special circumstances of the specific case. The Court explained:

"[T]he police action used the racial criterion as merely indicative of a greater probability that the interested party was not Spanish. None of the circumstances that occurred in said intervention indicates that the conduct of the acting National Police officer was guided by racial prejudice or special bias against the members of a specific ethnic group, as alleged in the complaint. Thus, the police action took place in a place of travelers’ transit, a railway station, in which, on the one hand, it is not illogical to think that there is a greater probability than in other places that persons who are selectively asked for identification may be foreigners; moreover, the inconveniences that any request for identification generates are minor and also reasonablyassumable as burdens inherent to social life".

(Rosalind Williams Lecraft v. Spain)

The case before the ICCPR Committee

Ms. Williams finally lodged a complaint under the Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Political and Civil Rights (ICCPR) before the UN Human Rights Committee for the alleged racial discrimination by the Spanish police. Ms. Williams supported her case with evidence on the general pattern of racial profiling conducted by the Spanish authorities and with the inefficiency of this policy. In particular, Ms. Williams pointed to:

- The traditionally high number of Spanish citizens of the roma minority that donít have Spanish ethnicity (according to a study presented this were 500-600.000 people, constituting about 1,5% of the Spanish population)

- The rising number of Spanish citizens with non-Spanish ethnicity immigrating from abroad (the legally foreign-born population had quadrupled between 1995 and 2004, including a significant share of non-European immigrants)

- The high number of non-Spanish immigrants with legal status of residency

- The high number of non-Spanish citizens of white skin color

(Rosalind Williams Lecraft v. Spain)

The ICCPR committee ruled that:

"[...] when the authorities carry out such checks, the physical or ethnic characteristics of the persons subjected thereto should not by themselves be deemed indicative of their possible illegal presence in the country. Nor should they be carried out in such a way as to target only persons with specific physical or ethnic characteristics. To act otherwise would not only negatively affect the dignity of the persons concerned, but would also contribute to the spread of xenophobic attitudes in the public at large and would run counter to an effective policy aimed at combating racial discrimination.:"

FF. Communication No. 1493/2006, Williams Lecraft v. Spain

The committee did not discuss the evidence presented by the complaint in detail, but seemed to agree with the arguments on the inefficiency of racial profiling in Spain. Moreover, the Committee did not consider an official policy of discrimination (such as an official ministerial order) as necessary but inferred from the fact that Ms. Williams was the single person who was interrogated? that the police acted in accordance with a policy of racial discrimination.

According to a recent Amnesty International Report, the policy of racial profiling in Spain has not stopped in spite of the ICCPR committee’s decision.

Spain police accused of racial profiling

The use of social science evidence:

In this case, as in the Israeli example, the national courts did not engage in evaluations of social science on the presence, the efficiency or the effects of racial profiling. While it may well be assumed that Ms. Williams introduced her arguments on the inefficiency of racial profiling based on the ethnic heterogeneity the modern Spanish society already before the national courts, they refused to address any finding of profiling. The Spanish Constitutional Court found no proof of an official order by the ministry to conduct racial profiling, while the evident racial influence in the concrete case was accepted as a legitimate part in the assessment of an illegal immigrant. The ICCPR Committee obviously gave more weight to the social background in Spain as established by the studies introduced by Ms. Williams when the ICCPR judged Ms. Williams’s treatment by the Spanish police. Yet, an explicit evaluation of social science evidence was not conducted by this institution either.

Germany

The discussion about racial profiling in Germany is a relatively recent development. While some NGOs had already complained about discriminatory police practices for a longer period of time, the public awareness of the issue was immensely enhanced by a 2010 case involving the Federal Police’s treatment of people of black skin color.

The facts:

Interview with Plaintiff in English:

Article on the proceedings in the first instance:

A is a German citizen. His skin color is black. In December 2010, then 24-year-old A travelled from the central German city of Kassel by train. In the train A was stopped by the German Federal Police who asked him for proof of his identification (such as a driver’s license or a national ID whose possession is mandatory under German law) without giving further reasons for this request. A requested to be informed about the reason for this order. The police officers gave a vague answer that did not disclose any specific reason for a suspicion against A, or any other justification for circumstances of danger that warranted the request. Therefore, A declined to present his ID.

Under German police law, the Federal Police is empowered to temporarily stop persons, interview them, to demand that identification is presented and to search carried items in order to prevent or interrupt the illegal entrance of the territory of the Federal Republic, insofar as - based on an evaluation of the police situation or the experiences of the border police – it is to be assumed that these trains are used for such illegal entrance.

Under this law, the federal police have to prove that there is general experience of illegal immigration on certain train routes. Once this general risk is established, the individual police officer has usually broad discretion whom to interrogate or question on the train. Nonetheless, discretion under German police law is limited by the rule of abuse of discretion which encompasses, inter alia, the violation of fundamental rights such as the prohibition of racial discrimination under Art. 3 (3) of the Basic Law (Grundgesetz).

A was forced to leave the train, his backpack was searched and he was taken to a federal police station in Kassel to be questioned. There his fingerprints and photographs were taken and he was temporarily detained. Finally, A decided to present his driver’s license as prove of his German citizenship, upon which he was released immediately. A complained that he felt resembled of methods of the Nazi-SS for which he was criminally charged with slander. Convicted in the first instance, A succeeded with his criminal appeal before the state court.

In the criminal proceedings against A, one of the two police officers who controlled A in the train testified as witness that he would search for persons in trains "who looked like illegal immigrants". One criterion, among others, was a person’s skin color. A had caught his attention due to his skin color.

A applied to the administrative court of Kassel against the control of identity claiming his treatment should be declared as illegal and as constituting a violation of his individual rights for the reason that the Federal Police had discriminated him based on his race.

The decision of the Kassel Administrative Court (proceeding 5K 1026111.KO)

In the administrative proceedings before the Kassel Administrative Court, A’s lawyer argued first that the conditions of the Federal Police Law were not met as the police could not give objective proof of the risk of illegal immigration in the train A used and second that –even if arguendo such a risk could be established – the police’s control was based on the race of his client and the discretion of the individual police officer under the German Police Law had been abused to a violation of Art. 3 (3) Grundgesetz (the constitutional prohibition of racial discrimination). As proof, the testimony of the officer about his profiling policies was introduced.

The Federal Republic of Germany as defendant argued the regional trains deployed between Kassel and Frankfurt/Main would, according to police situation evaluations of the Federal Police, be used for illegal immigration and other crimes under the Law of Residence. This resulted from a regularly actualized situation report of the Federal Police Circuit of Kassel. For instance, in the 3rd quarter of 2010 8,345 interviews had resulted in 330 findings of crimes and misdemeanors under the Law of Residence and to the tracing of searched subjects. These reports showed that irregular migration currents moved from West to East and from North to South on the relevant train net in Hesse (the state in which Kassel and Frankfurt are located). Regional trains were the preferred means of transport for illegal immigrants as a lower pressure of police investigations was expected there. The issue of the alleged abuse of discretion was not addressed at all.

The ruling chamber agreed with the state’s submissions:

"The requirements of § 22 (1a) of the Law of the Federal Police were met in the case at hand. Contrary to plaintiff’s view, respondent has given plausible summary that the relevant railroad track is used for illegal entrance, according to the evaluation of the police situation reports and corresponding border police experience. The chamber draws this conclusion especially before the background that the trains on this track accommodate passengers coming from the Rhein/Main International Airport and travelling in direction of the Hesse central first-contact asylum institution (Erstaufnahmeeinrichtung) in the City of Gießen. In the light of the numbers found by the state on the basis of its situation reports, the chamber sees no need for further investigations."

The problem of racial discrimination, though part of the summary of plaintiff’s submissions and though the police officer’s testimony regarding skin color as a criterion for police action was acknowledged in the presentation of facts by the chamber, was not addressed in the court’s ruling at all. The discretion of the police was not scrutinized after the general suspicion of danger had been established.

Comments on the lower court's judgment:

- German media reported widely about the case as did legal scholars. Many criticized the Federal Police sharply for their practice, which many perceived as a general practice of racial profiling of the Federal Police. In this light, the court’s decision not to address the alleged policy of racial profiling at all, which was a major legal question in the case, seems very doubtful. Although everyone who discussed the case thought of it as a landmark racial profiling decision, this was not part of the court’s ruling. Particularly, the court did not assemble any social science evidence if such a police policy existed in fact. This may well be due to the lack of numbers on persons questioned related to their race as race will never appear on German Police reports and scientific studies on the subject in Germany do not exist. Race is politically extremely sensitive in German political culture and nearly a political taboo, which can primarily be explained due to the German past of genocide and human right abuses. This causes the paradox that behind this curtain of silence a lack of control and information exists that makes it hard to determine existing discrimination against racial minorities.

- The Court uses social science to establish the alleged general risk for illegal immigration in trains. There appears to be no control of the statistics given by the federal police and a general trust in these findings. Despite the administrative judge’s role as an inquisitorial fact-finder, he relies on evidence given by a party without attempting to come to more specific social science evidence (at what time of the day does illegal immigration happen? How high is the success-rate demonstrated by the police compared with other railway tracks? What is a sufficient success-rate?) This is relatively indicative for the broad leeway given to the police by administrative court judges when only a "suspicion of danger" (Gefahrenverdacht) and no higher level of risk is required for a measure under German police law, as it is the case for identification control in trains by the federal police. This is the reason why the concept of "suspicion of danger" is highly controversial in German doctrine and some scholars argue that the legal concept is unconstitutional as interferences with citizen’s fundamental rights (albeit relatively minor interferences) are possible merely because of certain regional accumulations of past crimes or other indicators of generally increased risks out of one person’s control.

- For the question of abuse of discretion in the individual case, however, there was clear evidence that the police officer’s behavior constituted racial profiling. Other passengers stated that it was obvious that A was targeted as the single passenger merely due to his skin color. This was corroborated by the police officer’s testimony on his profiling decisions. The court simply ignored these circumstances, which might well constitute an additional violation of A’s fair trial rights but, additionally, could also be an example for a judicial result-oriented approach. The judges know that racial profiling does not comply with the constitutional non-discrimination rule but they might have a pre-concept of blacks as an important part of illegal immigration and do not want to interfere with a police practice they see as efficient to tackle illegal immigration.

- Even more significantly, in a prior decision of the Kassel Administrative Court on the question of whether A should be granted legal aid for the proceedings. A’s motion to have legal aid was dismissed for the reason that his suit was obviously without expectation of success. A major reason for this holding was that it would be justifiable for a police officer on his search for illegal immigrants to exercise the discretion which persons to ask for their identity according to their appearance, which explicitly (besides clothing, behavior, and speech) included their race. It is nearly bizarre that the court did not address this major ruling in the decision on the merits of the case as this statement was the central legal argument to uphold the practice of the police. In the financial aid decision the court demonstrated that it would base its decision on this interpretation of the law, but later tried to keep this problematic approach as secret as possible by not stating it in the reasoning on the merits.

The Appeal

The Kassel higher administrative court (the highest administrative court in the state of Hesse) decided that A could appeal against the lower court’s judgment because of the general importance of the legal questions raised on May 8, 2012.

http://www.anwaltskanzlei-adam.de/download.php?f=24dfb08877451d2eedfbf1c9a98dd78a

In his complaint against the original refusal to admit the appeal by the lower court, A’s lawyer relied on the weakness and ambiguity of the police data on the frequency of illegal immigration on A’s train. He pointed to the fact that the Federal Police had to concede that the among the breaches of the Law of Residence they found in this train, a maximum of 10 cases per quarter in 2010 constituted illegal entrance of the Federal Republic. He also criticized that it was neither stated how many persons were transported on how many trains in this region, nor a comparative number of other regions, such as border regions. A’s lawyer claimed that the administrative’s court level of scrutiny was too lax. Secondly, A’s lawyer specifically emphasized the lower court’s position in the legal aid decision against A, which had not been touched upon in the final judgment of the lower court and which was evidentially showing that the court tolerated racially discriminating practices of the police to justify A’s control..

The judgment of the Hesse higher administrative court was eagerly anticipated by the German public, especially the legal community. While statistics on the use of racial profiling by the German police do not exist and German public institutions deny any such practices, some observers noted that they saw the case as one example of a well-known informal practice by the German police.

The proceedings ended with a victory for A – but without a judgment.

The police – obviously due to the public pressure and the decision of superior officials – apologized for their behavior in court, which A accepted. The federal police agreed on the illegality of the decision to use their discretion in racially-influenced ways but still denied that this was more than a single exceptional case of abuse of discretion. The court, thus, declared the case settled, which discharged it from the duty to render an opinion on the merits of the case. However, the court ruled that the Federal Republic had to carry the costs of the proceedings and quashed the lower courts’ judgment as legally erroneous, which clearly indicated the higher courts’ legal position on the merits of the case.

Racial profiling before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR):

The European System of Human Rights forms a second layer of judicial control over state acts above the domestic court system. After the exhaustion of local remedies, an applicant can directly file a complaint with the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). National practices of racial profiling in the member states of the European Convention of Human Rights are a matter of concern for the ECtHR which sees such policies as inconsistent with the ECHR as the following case against the United Kingdom demonstrates:

Gillan and Quinton v. United Kingdom

In the present case the two applicants were stopped and searched by the police while on their way to a demonstration. Mr. Gillan was riding a bicycle and carrying a rucksack and Ms. Quinton, a journalist, was also ordered to stop filming in spite of the fact that she showed her press cards.

The court focused on the police power in the United Kingdom to stop and search individuals without reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing. According to sections 44-47 of the Terrorism Act 2000, if a senior police officer considers it "expedient for the prevention of acts of terrorism", the officer may issue an authorization permitting any uniformed police officer within a defined geographical area to stop and search any person and anything carried by him or her.

Although constrained by the text of the Convention (European Convention on Human Rights) and therefore deciding the case in terms of its "accordance with the law", namely with its article 8 – right to respect for private life, the Court takes different elements into account.

It claims that this wide discretion conferred on the police represents a serious interference "because of an element of humiliation and embarrassment." Moreover, as the officer’s decision, like in the present case, might be exclusively based on "hunch" or "professional intuition", it is not necessary for the officer to demonstrate the existence of any reasonable suspicion, being the sole proviso "that the search had to be for the purpose of looking for articles which could be used in connection with terrorism."

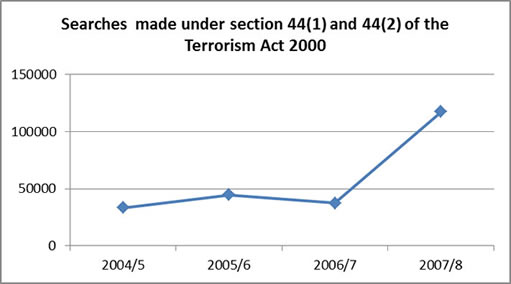

Furthermore, the Court also based its opinion on the annual reports from the Secretary of State. These entail information on the criminal justice system with reference to avoiding discrimination on the ground of race, containing statistical and other evidence showing the extent to which this resort is used by police officers. The reports recorded a total of 33,177 searches in 2004/5, 44,545 in 2005/6, 37,000 in 2006/7 and 117,278 in 2007/8.[1]

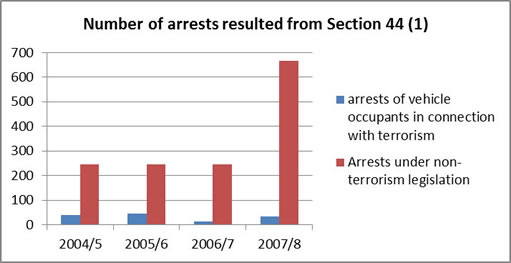

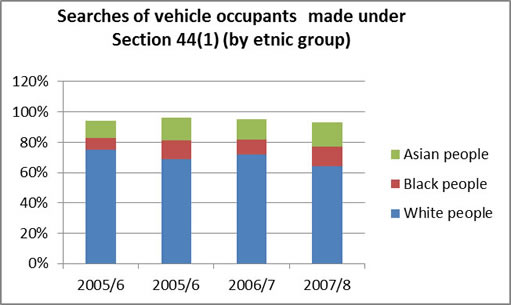

These reports noted that none of the many thousands of searches relate to terrorism offences, on the contrary, arrests for other crimes followed searches under section 44. Moreover, these reveal numerous examples of poor and unnecessary use of this power, showing cases "where the person stopped was so obviously far from any known terrorism profile that, realistically, there was not the slightest possibility of him/her being a terrorist, and no other feature to justify the stop". In addition, even though the present case did not concern black or Asian persons, the available statistics further prove that these are disproportionately affected by the powers. Therefore the Court expressly stated its concern about the disproportionately affect of the too broad power granted to the police.

In conclusion, the Court found that there was a clear risk of arbitrariness in granting such broad discretion to a police officer. It states that the powers of authorization and confirmation as well as those of stop and search "were neither sufficiently circumscribed nor subject to adequate legal safeguards against abuse"; being therefore not "in accordance with the law in violation of Article 8."

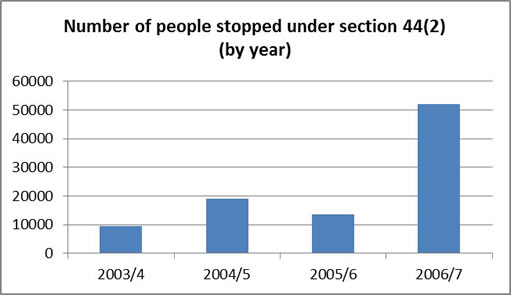

In order to better understand the Reports used by the Court, here are some graffics with the data from the "Statistics on Race and the Criminal Justice System – 2006" and "Statistics on Race and the Criminal Justice System 2007/8";

Preventive Detention

Under their rules on preventive detention, many European countries have laws that allow for the limited or even indeterminate involuntary incarceration of a person who has committed a crime and is seen as extremely dangerous for society even after the individual’s criminal imprisonment has ended. Preventive detention is traditionally not seen as a punishment as it does not fulfill a retributive purpose, does not depend on the culpability of a perpetrator, nor is it meant to deter third persons from committing crimes.

However, preventive detention in many European countries has certain similarities with criminal punishment. For example, preventive detention in Germany is provided for in the Criminal Code and a criminal court can order preventive detention in the course of criminal proceedings against a perpetrator. The detained persons are held in the same buildings as criminal prisoners and their treatment is not fundamentally different from that criminal

prisoners would receive.

The detainment of a person on the basis of the allegation that he or she is a menace to society means an extreme far-reaching encroachment on this person’s rights and liberties, especially if the detainment is ordered indeterminately. The constitutional questions arise concerning what level of risk of a person’s criminal future behavior renders the detainment of this person proportional, and how this risk can be properly assessed by the state.

It was, inter alia, these issues that were addressed by the judgment of the German Constitutional Court in its 2004 decision on the German law on Preventive Detention:

Germany

Legal background:

Preventive Detention (Sicherungsverwahrung) was first introduced in the German Criminal Code in 1933 under the Naziregime, in a doctrinal shift from the punishment of a person’s specific illegal act to an understanding of certain persons as a general and constant danger to society. After the liberation of Germany from fascism and the introduction of fundamental freedoms under the new constitution (Grundgesetz), this concept of a general classification of perpetrators as constantly dangerous was abolished. However, since a lingering social need for the protection of society from extremely dangerous criminals still was perceived, preventive detention was not eliminated but rather substantively reduced in its scope and limited to 10 years of detention.

The assessment of risk required to detain a perpetrator is based on a two-part analysis: One part of this was the legislative decision that certain current and previous criminal acts were necessary to establish the dangerousness of a person (usually conviction for an intentional crime for at least two years if the convicted had already been sentenced for two prior intentional crimes for at least one year imprisonment each and at least for two years for one of the crimes), which constitutes a fixed static factor of risk assessment. Additionally, a comprehensive individual assessment of the criminal, including testimony of two experts, had to result in the finding that due to his dispositions to commit dangerous crimes that cause grave bodily or mental harm to the victims or severe economic damages, the person would pose a danger to society (§ 66 German Criminal Code).

In 1998, the law on preventive detention was substantively changed. The new § 67 of the Criminal Code eliminated the 10 year-limit for preventive detention and allowed for indefinite preventive detention if after 10 years a new thorough assessment of the personal risk would warrant the assumption that a defendant committed crimes that would cause grave bodily or mental harm to victims.

Moreover, since 2004, a court may order a person to be indefinitely detained that was already scheduled to be released from prison or from a 10-year detainment under the old rules if the person turned out to be dangerous in prison, even if preventive detention was not considered in the original judgment at all (retrospective preventive detention, nachträgliche Sicherungsverwahrung).

The number of persons in preventive detention in Germany increased from 257 to 500 between 2001 and 2009 (Christopher Michaelsen "From Strasbourg with Love, - Preventive Detention before the German Federal Constitutional Court and the European Court of Human Rights)

The M Case:

Facts according to the ECtHR press release:

M is a German citizen, who was born in 1957. After a long history of previous convictions, the Marburg Regional Court convicted him of attempted murder and robbery and sentenced him to five years' imprisonment in November 1986. At the same time it ordered his placement in preventive detention (Sicherungsverwahrung), relying on the report of a neurological and psychiatric expert, who found that the applicant had a strong tendency to commit offences which seriously harmed his victims' physical integrity, that it was likely he would commit further acts of violence and that he was therefore dangerous to the public. After having served his full prison sentence, the applicant's repeated requests between 1992 and 1998 for a suspension on probation of his preventive detention were dismissed by two regional courts, respectively relying on an expert report and taking into consideration the applicant's violent and aggressive conduct in prison. In April 2001 the Marburg Regional Court again refused to suspend on probation the applicant's preventive detention and ordered its extension beyond September 2001, when he would have served ten years in this form of detention. This decision was upheld by the Frankfurt am Main Court of Appeal in October 2001, finding, as had the lower court, that the applicant's dangerousness necessitated his continued detention.

Both Courts relied on Article 67 d § 3 of the Criminal Code, as amended in 1998 allowing for the retroactive extension of preventive detention that was limited to 10 years under the prior rules. In February 2004, the Federal Constitutional Court dismissed the applicant's constitutional complaint against these decisions in a leading judgment, holding that the prohibition of retrospective punishment under the German Basic Law did not extend to measures such as preventive detention, which had always been understood as differing from penalties under the Criminal Code's twin-track system of penalties on the one hand and measures of correction and prevention on the other.

The German Federal Constitutional Court’s 2004 decision

Judgment - 2 BvR 2029/01 -– of 5 February, 2004

The legislative margin of appreciation vs. social science

The Federal Constitutional Court (FCC) first addressed the issue of proportionality of preventive detention in general with respect to the severe interference with the detainee’s fundamental right of personal freedom. The Court argued that encroachments on this legal good were generally only admissible if the protection of other citizens or of the common good required it under the principle of proportionality. Society’s need for protection against expected significant violations of legal goods had to be contrasted with the detainee’s claim for personal liberty as a corrective; they had to be brought to a balance in each individual case.

The FCC, however, refused to challenge the concept of preventive detention as such and gave great leeway to the legislative branch:

"In assessing the suitability and necessity of the means chosen to reach the aspired aims and in rendering its estimation and prognosis of the threats to individuals or the common good, the legislator has a margin of appreciation, which […] can only be reviewed to a narrowed extent by the Federal Constitutional Court. This been said, the legislator’s assessment that it was suitable and necessary to strike down the time limit for first-time-detainees to improve the protection of society against dangerous criminals cannot be objected.

Whether the aggravation of the rules of the law of preventive detention was triggered by an objective increase of violent criminality, or – as some critics claim – only addressed an increased social perception of threat, is not to be evaluated by the Federal Constitutional Court. It is primarily for the legislative to decide which measures it wants to take in the interest of the common good based on its criminal political visions and aims and within its margin of appreciation. Only apparently flawed decisions of the legislator are subjected to correction by the constitutional court; this does not apply to the case at bar." (Judgment - 2 BvR 2029/01 -– of 5 February, 2004 para. 99 f.)

Risk assessment of the judge and social science

The second question the court dealt with was the reliability of judicial risk assessment in individual cases under the legal aspect of proportionality.

"The uncertainties of the prognosis, which is the basis for the detention, affect the minimum standards for expert testimony employed for the prognosis and the evaluation in front of the background of the prohibition of disproportional means. However, they do not render the limitations of personal freedom unsuitable or unnecessary. Decisions based on a prognosis do always include the possibility of a false prognosis, but such decisions are inevitable in law. A prognosis is and will always be the foundation of protection against danger, even if a prognosis might be insufficient in a specific case.

Moreover, the knowledge about risk factors in the practice of forensic psychiatry has significantly increased in recent years so that it is possible to make relatively good and reliable prognostic statements on a fraction of delinquents. Both experts who were heard in the oral argument agreed that a certain and determinable part of subjects accumulated so many risk factors that a danger could be prognosticated with certainty. Even though the testifying experts disagreed as to the share of relatively safe prognosis, a prognosis forms a proper basis for the decision, particularly in the rare cases of high-level dangerousness § 67d (3) StGB addresses." ( Judgment - 2 BvR 2029/01 -– of 5 February, 2004para.101 f.)

After this general statement, which agreed with the possibility of sufficiently accurate risk assessment to render indeterminate preventive detention proportional, the court imposed specific procedural and substantive standards that courts had to follow in each individual case to guarantee proportionality to every subject who would be assessed for his dangerousness such as the independence and qualifications of the testifying expert appointed? by the judge, and procedural rights of the defendant. The FCC gave especially strict rules to the extension of preventive detention after 10 years:

"The decision to continue the detention pursuant to §67d (3) StGB [after 10 years] has to rely on an expert’s advisory opinion that gives consideration to the special magnitude and to the exceptional character of this decision. Care has to be paid to a sufficient substantiation of the medical advisory opinion that lives up to recognized scientific standards. The danger of repetitive routine-evaluations has to be coped with by the judge’s diligent choice of experts." (Ibid.Para. 114)

According to the Court this means:

- The expert should not work for the institution where the detained is incarcerated because internal affairs of the institution and the patient-therapist relationship should not affect the expertís opinion. Moreover, in many cases it would be appropriate to find an expert who has not been involved in the case before.

- The expert should be a medical specialist with education and work experience in psychiatry

- The expertís advisory opinion, however, does not replace the independent decision of the judge but only prepares the latter: "After receiving expert advice, the judge has to take an independent prognostic decision, in which he has to subject the medical advisory opinion to judicial control. This control does not only encompass the result of the expertís assessment but extends to the quality of the entire process of the assessment." (Judgment - 2 BvR 2029/01 -– of 5 February, 2004Para. 120)

- The judge has to test if the expertís advisory opinion meets certain minimum standards. The advisory opinion has to be reproducible and transparent. The expert has to comprehensively state the facts he sees as relevant in justifying his findings, he has to explain the methodology he uses and to disclose his hypotheses. The expert then has the duty to come to a specific statement of risks related to the perpetratorís future legally relevant behavior that allows the court to answer the legal question of ß 67 d (2) (future dangerousness) independently.

- Substantively, the expertís evaluation has to be based on a sufficiently broad factual basis that covers and evaluates the personality of the perpetrator as well as the criminal acts he has committed. This evaluation has to take into consideration all central aspects of the individualís life, such as his social background and social influence, his personal status before he committed the crime that caused the question of detention to arise, as well as his personal development after he has committed the crime. Moreover, the hypothetical behavior of the detained under less severe measures than complete detention has to be assessed.

Comment on the Federal Constitutional Court's use of social science

The FCC rejects to engage into deeper discussion about the general need for preventive detention as a means to fight dangerous criminals. This is typical for a general pattern of judicial self-restraint, which the FCC follows in controlling legislative acts on their socio-empirical correctness. The legislative is given a broad margin of appreciation when it comes to the assessment of social reality. The standard of "evident flawed decisions" is nearly never reached. In contrast to this, the FCC more actively discusses the use of social science in the assessment of the risks of individual detainees. This question, though it is interlinked with the first question, does not challenge the legal framework as such but gives interpretation to the legal framework in a way that the form of risk assessment based on a specific use of social science remains proportional. This was in this case partly criticized by scholars as studies on false positives in preventive detention risk assessment were clearly demonstrated by social science studies. The court does not become quite specific in its statement how accurate modern scientific methods could assess the risk emanating from a perpetrator and it does not make clear what these methods are. It happens quite often that German courts evoke the standards of "state of the art" or "recognized scientific methods" with respect to scientific evidence without getting any more accurate what they think this is.

The rules on risk assessment in preventive detention cases and as interpreted by the FCC may be classified as a clinical form of risk assessment. Even though emphasis is laid on the scientific standards to be used in the risk assessment, the court eventually remains free to judge about risks. Even though scientists will support the judge with a detailed report about different risk-factors the balancing of these factors will eventually retain in the hands of the judge. "Dangerousness" is seen as a legal question in the last instance, not a purely factual one so that, in the end, the scientist can only be an assistant to the legal expert on the bench. The judge will have to explain in details why he decided not to follow an expert and will be subjected to control by the higher courts, however legally not even the best and most precise expertise is strictly binding authority. In fact, however, it is hard to imagine which judge wanted to take responsibility for the consequences of scientifically predicted and avoidable violent crimes committed by a re-offending perpetrator.

The legal dispute between the FCC and the European Court of Human Rights

The question of appropriate individual risk assessment as precondition for the proportionality of indeterminate detention was not the only legal question raised in the proceedings before the Federal Constitutional Court.

As has already been said, preventive detention, though it shares some characteristics with a criminal punishment, does not classify as a criminal sanction under the concept of German Criminal Law. Still, it was to be considered if the constitutional protection of Art. 103 (2) Grundgesetz (nulla poena sine lege previor) should not be extended to preventive detention so as to avoid circumvention. The FCC decided that the strict prohibition of this rule would not apply to preventive detention but that rather a general protection of legitimate expectations (Vertrauensschutz – literally: "protection of trust") would result from the German rule of law principle (Rechtsstaatsprinzip). This merely relative protection, however, allows for a balancing of interests and the FCC concluded that the state’s principal duty to protect its citizens from harm to life or limb would thus justify the retroactive application of the new rules to old cases. Secondly, and linked with the first aspect, the constitutional court ruled that the differentiation between a criminal sanction and preventive detention could not be merely a formal legal one but that it had to make a difference in reality. However, the FCC said that it was not for the Constitutional Court to give concrete directives in that matter and gave broad discretion to the legislative in framing the conditions of preventive detention.

M v. Germany (application no. 19359/04)

As the Court’s judgment concerns the retroactive extension of a prisoner’s preventive detention, the Court examines the tension between the State’s desire to keep dangerous people off the street and a convicted offender’s right of liberty.

The Court unanimously concluded that the applicant’s preventive detention beyond the ten-year period amounted to a violation of Article 5 § 1 – right of liberty, lawful detention. It found that there was not sufficient causal connection between the conviction and the extension. Moreover, the Court established that the applicant’s continued detention had not been justified bythe risk that he could commit further serious offences if released, as these potential offences were "not sufficiently concrete and specific".

An essential point of the decision was the qualification by the Court of preventive detention as a penalty. Therefore, the extension constituted an additional penalty which had been imposed on the applicant retrospectively, since at the time of the offence the applicant could have been kept in preventive detention only for a maximum of ten years.

Furthermore, based on the findings of the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights and the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture about preventive detention in Germany, the Court concluded that there was currently no sufficient psychological support specifically aimed at prisoners in preventive detention that would distinguish their condition of detention from that of ordinary prisoners.

The reports further stated that preventive detention, with its aim of crime prevention, should require a "high level of care involving a team of multi-disciplinary staff, intensive work with inmates on an individual basis within a coherent trade work for proration towards release."

Thus, the Court also concluded that there had been a violation of Article 7 § 1 - nulla poena sine lege previor.

The German Answer to the ECtHR:

Judgment of the FCC 2 BvR 2365/09 et. al. of 4 May 2011

As response to the ECtHR decision in the M case, the FCC drastically changed its opinion and overruled its prior decision, when the law on the retrospective application and retroactive extension of preventive detention was challenged again in 2011.

Though the ECHR is not part of the German constitution and has merely the rank of a usual law. The FCC, however, applies the provisions of the Grundgesetz in a way that should give full effect to Germany’s obligation under International Law (including the ECHR) as far as this is possible by means of legal interpretation.

Due to this the FCC now hold that the retroactive application or retroactive extension of preventive detention violated the German Constitutional prohibition of legitimate expectations (the court still refused to apply the strict prohibition of criminal ex-post-facto laws but interpreted the rule on legitimate expectations in a way that was akin to this strict prohibition).

Moreover, the FCC agreed that the requirement of distance between a criminal punishment and preventive detention was not met and preventive detention thus was not proportional.

The FCC demanded that the ECtHR’s decision had to be taken into account when deciding on the form of detention:

"By a liberty-oriented execution aimed at therapy which clearly shows to the detainee under preventive detention and to the general public the purely preventive character of the measure. What is required for this is an overall concept of preventive detention with a clear therapeutic orientation towards the objective of minimizing the danger emanating from the detainee and of thus reducing the duration of the deprivation of liberty to what is absolutely necessary. The placement in preventive detention must be visibly determined by the perspective of regaining liberty" (Judgment of the FCC 2 BvR 2365/09 et. al. of 4 May 2011 3rd leading sentence).

The constitutional court adopted specific orders to the legislative how to structure preventive detention in order to suffice this requirement.

The FCC then concluded:

"The present provisions on preventive detention, and consequently their actual execution, do not satisfy these requirements."(Ibid. Para. 119)

To demonstrate this, the court evaluated two studies on the current conditions of preventive detainees:

- The actual current execution of preventive detention falls short of these requirements: In the oral argument, expert testimony was given, which is supported by recent scientific findings that the distance of preventive detention to criminal punishment is not guaranteed. Studies showed that only about 30% of the detained received therapeutic treatment though 79, 3 % of the detained showed the need for treatment. The cause for this is, according to the same study, not only stemming from the sphere of the detained, but part of the lack of adequate personal and material resources in the detention facilities. For a freedom oriented therapeutic approach more resources will be necessary.

- According to a second study, of 536 persons in preventive detention in March 2010 only 83 were in a facility for social therapy despite the common sense that such facilities can increase the detained expectations to be released. This is also due to a lack of resources in such facilities but also to their reluctance to integrate preventive detainees. Moreover, the combined treatment of criminals and preventive detained in such facilities can lead to adverse consequences.

After having established a severe violation of fundamental rights, to avoid a "legal vacuum", the FCC did not declare the unconstitutional provisions void but ordered their continued applicability for a limited period of time. The FCC took that decision because the declaration of nullity of the relevant provisions had the consequence that a legal basis for continuing preventive detention would be lacking; all persons placed in preventive detention would have to be released immediately, which, according to the FCC, would cause almost insoluble problems to the courts, the administration and the police. The FCC did not present any evidence as to this need, but apparently relied on the Federal Republic’s submission that the liberation of all detained could cause a catastrophic threat to security. During the period of provisional application until the legislative adopted new rules, the old provisions had to be applied under especially strict rules on proportionality allowing only for the detention of the most dangerous criminals.

Additionally, with respect to the retroactive application of preventive detention contrary to the prohibition of ex post facto rules, the FCC ruled that in such cases a justification of preventive detention would only be possible under Art. 5 (1) 2 e) ECHR, which required as central criterion the "unsound mind" as understood by the ECtHR as a true mental disorder warranting compulsory confinement.Moreover, the validity of continued confinement must depend upon the persistence of such a disorder". In accordance with the ECtHR jurisprudence "true mental disorder" was not a term of art and left the member states a certain margin of appreciation. While a merely social conspicuous behavior fell short of a "true mental disorder" dissocial disturbances of personality and psychopathy could be included without prescribing what the exact meaning of such a dissocial disturbance is. The precise definition of such a disturbance is left to a member state’s legislation. With regard to this, the court opined that the German Therapy Placement Act, which entered into force on 1 January 2011, had to be drawn upon for this. With this Act, the German legislature, taking into account the special requirements of the European Convention on Human Rights, had created another category for the placement of persons with mental disorders who are potentially dangerous due to their criminal offences which focuses on the present mental situation of the persons affected and their dangerousness resulting therefrom. Under this law a prior crime is taken as the indicator for the dangerousness of a person while the reason for the person’s detainment is not the mental state of the person at the time of the crime but the person’s ongoing state of a mental disturbance that resulted in the future dangerousness of the person in the subsequent proceedings. A third category between the mentally undisturbed but dangerous perpetrator and the insane and therefore legally excused person that can be detained in a closed hospital is thus created.

Comments:

- Social science is used to determine whether the current concept of preventive detentions lives up to the requirement of distance and furthers the requisite aims of therapy and rehabilitation.

- The legislative risk-assessment that preventive detention is necessary in general, is challenged neither by the ECtHR nor by the FCC.

- The FCC sees itself compelled to base preventive detention on an alternative legal foundation due to the ECtHR decision. European law makes the FCC shift the standard of risk assessment from a clinical, liberal and individualized judicial risk assessment which is based on proposals of experts but eventually fully in the hand of the judge, to the need for concrete, definite psychological evidence for an unsound state of mind as a psychologically defined narrow set of disturbances outside the discretion of a judge. During the phase of a provisional application of an unconstitutional norm, social science is in fact given broader power in risk assessment as judicial discretion does not fit the concept of mental disturbance. This, however, is limited to the cases of the retroactive imposition of preventive detention. In a later decision, the FCC very clear about the ongoing applicability of the old rules on risk assessment – as stated in the first M decision - in preventive detentios soon as the "requirement of distance" to criminal punishment is reached. In other words: As soon as the actual detention does not resemble a punishment anymore, the FCC would again allow for the broader clinical risk assessment under the standard in its first M decision.

- The constellation in the M case and the FCC’s later judgment on preventive detentions resembles the U.S. Supreme Court’s judgment in the Hendricks' case (Kansas v. Hendricks - 521 U.S. 346 (1996)). Both addressed the legal questions not only of risk assessment of dangerous criminals and faced the problems of the ex-post facto laws and the differences between punishment and detention. Hendrick’s rule that courts would not have to follow a narrow set of mental disturbances when assessing a person’s lack of control but that the judgment of dangerousness is more liberal, resembles the FCC’s original finding in the M case but would not suffice the narrow assessment criteria of the ECtHR under Art. 5 (1) 2 e) ECHR.

- Neither the European Courts nor the U.S. Supreme Court in Hendrick’s explained the justification and rational for the special treatment of persons having a mental disorder, nor did they delineate the types of a mental disorder that would justify preventive detention because of a person’s lack of control.

There are some major differences to the use of social science in risk assessment by American courts:

- No adversarial expert testimony, inquisitorial responsibility of judge to inform himself by expert testimony. Though the judge is free, in fact the judge will often follow the expert.

- No strict rule on the use of expert testimony such as Daubert in German Criminal Procedure and Civil Law Systems in General (no jury to be protected, no high danger of biasing? Biased? testimony). The Code on Criminal Procedure gives discretion to the judicial selection of experts, but the FCC interprets the general rules on the introduction of expert testimony narrower in this specific case due to the constitutional requirements (example for constitutionalization of the code rules by constitutional case-law) Ė a "preventive-detention Daubert" decision. Both the Code on Criminal Procedure and this FCC decision presuppose that a judge is actually able to assess the quality of an expert and the methodology that is employed. Moreover, the judicial assessment includes the plausibility of the expertís finding even if the judge does not find that the methodology was flawed.

- The systemic reliance on individual judicial verdict and the reduced role of social science to prepare this individual judgment would not allow for a categorization of perpetrators in risk-groups. However, the legislative has given a fixed risk-categorization by demanding specific past crimes before any individual risk assessment can take place at all.

- Crucial importance of neutrality of expert.

- Indicative for different meaning of fact-finding and truth in criminal procedure in general.

- In Israel, preventive detention is described differently, as an arrest of individuals being a threat to the general population without a trial, not keeping dangerous prisoners under custody after their jail time is over. This is why Israel was not included in this overlook.

Conclusions

Risk assessment is a matter of balancing values, on the one hand state intervention and ensuring the safety of the citizens and on the other hand the right to liberty of the individual, a basic right in the liberal state.

The different systems reflect different balances as well as the different perspectives of the use of social science evidence. The adversarial system leaves the science in the hands of the parties, on the other side the inquisitorial system leaves the science brought to court in the hands of the judge.

Apart from this general difference between inquisitorial and adversarial systems, risk assessment also depends on cultural perceptions of values to be protected and the level of safety to be guaranteed on the cost of certain liberties. This has significant effects on the different ways how risks are assessed in a society and on the determination what risks are acceptable in a state and which are not.

In Europe, the combined effect of an inquisitorial judge with strong powers in fact finding combined with a greater reliance on state action to fight risks in many European states compared with the US, tends to reduce the impact social science would have in a court’s risk assessment.

In the European countries, the use of social science in court is rather limited and the focus is on independent expert testimony in a concrete, specific case that presents the expert’s individual professional expertise rather than on broad studies that demonstrate a general social background which could be used for a number of succeeding cases. A social framework as social authority would often conflict with the eventual authority and the tendency to rely on the state’s risk assessment as a normative authority of last instance.

The legal rights revolution in Europe, in the sense of a focus on individual rights and freedoms, which is caused by the European integration as well as directly enforceable fundamental rights in the national constitutions as a relatively young development, have however caused a stricter scrutiny of state actions in the fight against risks. As the decisions of the ECtHR demonstrate, the more risk assessment comes under scrutiny the more weight will also be given to social science authority to guarantee more reliable and more reasonable limits to judicial, executive and legislative discretion in risk assessment.