Eyewitness Testimony and Making a Murderer

Compiled by Mario Roque, Kayla Burd, Christie Diaz, and Alexandra Kitson

Introduction

Eyewitness identification procedures may be used for a myriad of reasons. For instance, after identifying a suspect, police may use identification procedures to “test a witness’ ability to identify the suspect as the perpetrator.” In other situations, identification procedures might be used during investigations to prove probable cause (e.g., for a search warrant, or to apprehend a suspect for further questioning). In many cases, the positive identification of a suspect by an eyewitness is powerful evidence which may be used by the prosecution.1

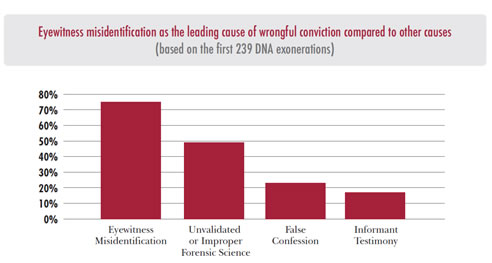

Current data suggest that eyewitness misidentification is the largest contributor to wrongful convictions of those exonerated through DNA testing.2 In fact, eyewitness misidentification was a factor in the wrongful conviction of more than 175 individuals (over 75%) who were eventually exonerated.3 These cases typically involve several additional complications. For instance, multiple eyewitnesses may misidentify the same person (this has occurred in 38% of the misidentification cases mentioned above).4 Further, eyewitness testimony was the central evidence in over 50% of such cases.5 It is important to understand the causes of eyewitness misidentification so that we may help improve procedures and techniques used to gather such important information. When misidentification of a suspect occurs, individuals may be wrongfully convicted, and the true perpetrator(s) may go free. In fact, in at least 48% of the eyewitness misidentification cases where the true perpetrator remained free, these individuals committed additional violent acts while the wrongfully convicted individual was imprisoned.6

Credit: The Innocence Project7

I. Legal Standards for Eyewitness Identification

The U.S. Supreme Court has addressed both the admission and reliability of eyewitness evidence in criminal cases.

Their 1977 decision in Manson v. Braithwaite8 provides a two-step process for determining if an eyewitness identification that was obtained using an improper procedure should be excluded at trial. First, it must be demonstrated that the identification was obtained from the eyewitness using a faulty technique. Second, the court should use the following criteria to assess the reliability of the eyewitness identification:

- The eyewitness’s opportunity to view the perpetrator at the crime scene.

- The degree of attention the eyewitness focused on the perpetrator.

- The accuracy of the witness’s description of the perpetrator.

- The time elapsed between the witness’s identification of the suspect and witnessing the crime.

- The certainty of the witness’s identification of the suspect.

If the totality of these factors suggest that the identification is unreliable, it should be excluded at trial.9

The Supreme Court again examined eyewitness identification in its 2012 case Perry v. New Hampshire.10 Here, the Court ruled that the Due Process Clause only requires a preliminary judicial examination of an eyewitness identification to assess its reliability when the identification was procured under “unnecessarily suggestive circumstances arranged by law enforcement.”11

II. The Social Science of Eyewitness Identification

Much research has explored the strengths and weakness of eyewitness memory and identification from both basic and applied perspectives. For instance, basic research gives insight into the foundational processes of vision, attention, perception, and memory, all of which are important considerations when examining eyewitness testimony and identifications.12

Basic Principles of Vision and Memory

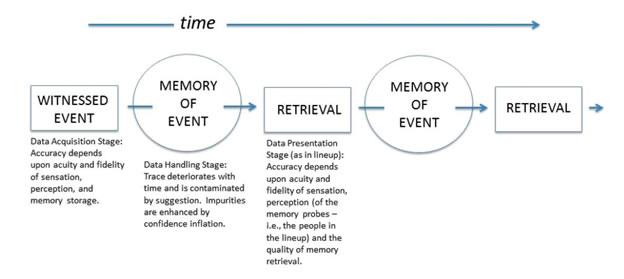

Eyewitness accuracy is dependent upon an eyewitness properly sensing, perceiving, remembering, and recalling events. All eyewitness identifications (accurate or inaccurate) are based on the initial opportunity to see an event occur. First, eyewitnesses take in visual information from the scene around them through sensation. Next, witnesses must determine what to look at or look for and where to focus his/her attention. Then, all of this information is combined and integrated into the perception of the event. These perceptions are then encoded and are processed in short-term working memory. However, working memory is limited in capacity. Eventually, these perceptions are consolidated into long-term memory and are stored. Later on, when the eyewitness is asked to recall the events, he/she must retrieve the related memories from storage. Vision, attention, and memory processes are very complex, and changes to memory may occur over time. Further, memory encoding, retention, and retrieval are all susceptible to inaccuracies and suggestion. Because these processes are naturally vulnerable, it is important to create and utilize procedures that best help eyewitnesses report on events that they have witnessed.13

Credit: Thomas D. Albright14

Applied Principles of Vision and Memory

This basic work has been used in a larger body of applied research examining eyewitness identifications, and the study of important factors related to witnessing crimes. It is important to note that the proper examination of factors relating to eyewitness testimony must include the exploration of both system variables and estimator variables.15

System variables are those relating to procedures and practices. An example of a system variable would be the instructions given to eyewitnesses: The interactions that eyewitnesses have with law enforcement officers, for instance, or the procedures used to elicit their memories may all impact the accuracy of eyewitnesses testimony. Further, these interactions can affect this testimony before, after, or even during the identification process.16

To some extent, the justice system can control certain system variables. For instance, the courts could utilize standardized jury instructions, and law enforcement could utilize standardized eyewitness instructions based on empirical research. Further, law enforcement officials can maintain neutrality during identification procedures, which can help ensure unbiased identifications by the eyewitnesses. Because research indicates that eyewitness testimony can be influenced by system variables (e.g., instructions, lineup procedures, verbal or behavioral cues from law enforcement), it is important to approach procedures and practices with caution and to properly conduct all procedures.17

Estimator variables are those which can impact the accuracy of eyewitness identifications which are characteristics of the eyewitness, or may be related to the context during which the eyewitness viewed the initial event. For instance, the encoding of the memory, the level of trauma to the eyewitness, the lighting or general nature of the conditions during the memory encoding, are all estimator variables. Estimator variables are typically studied within laboratories rather than in the field.18

Some of the most commonly researched estimator variables include stress, fear, exposure, and retention interval. When an eyewitness experiences high levels of stress and/or fear, memory for the event may be impaired. Further, the length of exposure (e.g., the amount of time that the eyewitness has to view the suspect) can impact overall accuracy of the memories for the event. For instance, longer exposure is associated with increased memory accuracy. Lastly, retention interval can play an important role in eyewitness accuracy: The retention interval is the amount of time between the initial witnessed event and the initial recollection of the details of that event. The longer the retention interval, the more difficult it can be to remember details from the event. Because individuals have little control over estimator variables, it is important to improve system variables in order to improve eyewitness identifications.19

Taken together, research into the basic and applied factors that impact eyewitness memory accuracy show that identification procedures are susceptible to several difficulties, including:20

- Variability in eyewitness identification procedures

- Suggestive lineup composition

- Social influence and cues from lineup administrators or sketch artists in lineups, show-ups, and composites

- Witness misunderstanding in the eyewitness ID procedures and investigations

- Susceptibility to suggestion of eyewitness confidence in the ID

As discussed above, estimator variables are outside of our control. Therefore, utilizing proper, unbiased procedures for witness identification is extremely important.21

In the video below, Dr. Elizabeth Loftus discusses the fallibility of human memory and gives examples of eyewitness misidentification.

Dr. Elizabeth Loftus - TED Talk - The Fiction of Memory22

III. Making a Murderer: Applying social science principles to the Avery case

Eyewitness Testimony in the Avery Case

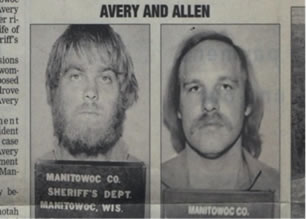

Making a Murderer evidences several of the problems with eyewitness testimony. For example, in the first episode of the series, police talk to a sexual assault victim about her attacker. Using the victim’s description, a police sketch is created. The police sketch artist used suggestive language, however, and coaxed answers and descriptions that appear similar to Steven Avery. Although the sketch was made shortly after the assault, the victim’s stress level at the time of the attack was extremely high. This factor gave rise to the possibility that her memory was not entirely clear. Indeed, it is apparent from the victim’s interview that her recollection was clouded and very susceptible to the artist’s proposals. Ultimately, the victim follows many of the artist’s suggestions and the sketch looks like Steven Avery.

In addition to helping with the sketch, the victim also identifies Avery as her attacker during trial. This identification came after investigators made other suggestive statements and the victim had viewed the sketch for an extended period of time. The sketch and identification were weighed heavily by the jury and formed a strong basis for finding Avery guilty. Eighteen years after being found guilty of the assault, forensic DNA evidence proved that Avery did not commit the crime. The victim’s identification and sketch were mistaken.

Similarly, in Avery’s murder trial,one of Avery’s nephews, Bobby Dassey, testifies about Theresa Halbach’s whereabouts on the day of her disappearance. Dassey states that when he left the Avery property shortly before 3PM, Halbach was no longer there. Further, Avery’s brother-in-law, Scott Tadych, testifies that he saw Bobby on the road around 3PM. In contrast to Dassey and Tadych, a school bus driver testifies that when she arrived at the Avery property around 3:30PM Halbach was still there taking pictures of a van.

Dassey and Tadych’s testimony are crucial to the prosecution’s case. They place Halbach at the Avery compound and give a timeline for her murder. Yet, the questions they raise are many. There is a significant delay between when Dassey and Tadych gave their testimony and the day of the event. Additionally, the bus driver was on a set schedule. She arrived at the Avery home within a ten-minute time frame on a daily basis. It is likely that she was able to gauge time better than Dassey and Tadych. Given this ambiguity, the jury was charged with the question of whose testimony to weigh more heavily – a question that they are likely not trained to handle.

IV. Eyewitness identification reforms and prevention of misidentification

Based on the above-mentioned research, many reforms and suggestions have been made.25 In many cases the suggested reforms are easy to adopt. To date, fourteen states have implemented such reforms either through changes to policies, court action, and law.26 Several jurisdictions, including Baltimore, Boston, Dallas, Minneapolis, Oklahoma City, Philadelphia, San Diego, San Francisco, and Tucson have implemented changes to their standard practices.27 Such reforms are well supported in scientific literature and are accepted by organizations such as the American Bar Association and the National Institute of Justice.28 Reforms and procedures include:29

- Documenting the confidence of eyewitnesses

- Lineup composition

- Recording identification procedures

- Sequential presentation of lineup members

- Training all law enforcement officers in eyewitness identification

- Utilizing double-blind lineup and photo array procedures

- Developing and utilizing standardized eyewitness instructions

- Conducting pretrial inquiries (E.g., judges should inquire about the eyewitness ID evidence before trial)

- Juries should be made aware of all prior identifications and the context of those IDs

- Provide scientific framework evidence through expert testimony or jury instructions to convey such information

Reforms in response to the Avery case

After Steven Avery was exonerated in 2003, the state of Wisconsin began pursuing reforms to its criminal justice system with the goal of reducing wrongful convictions. As part of these reforms, the Wisconsin Attorney General’s Office issued Model Policy and Procedure for Eyewitness Identification in 2005. This report provided the following recommendations to law enforcement.

- Use non-suspect fillers chosen to minimize any suggestiveness that might point toward the suspect.

- Use a “double blind” procedure, in which the administrator is not in a position to unintentionally influence the witness’s selection.

- Give eyewitnesses an instruction that the real perpetrator may or may not be present and that the administrator does not know which person is the suspect.

- Present the suspect and the fillers sequentially rather than simultaneously.

- Assess eyewitness confidence immediately after identification.

- Avoid multiple identification procedures in which the same witness views the same suspect more than once.30

In addition to model policies put forth by the Wisconsin Attorney General, the Wisconsin legislature passed a criminal justice reform package. This legislation required that police departments have written policies dictating procedures for eyewitness identifications.31

Conclusion

The jury generally weighs eyewitness testimony heavily. It is widely believed that memory is a static construction: unyielding to suggestion, social pressures, and the passage of time. But, as social science points out, eyewitness memory can be changed and adapted over time, it is susceptible to various social and biological pressures, and sensitive to misunderstandings. Given these issues, it can be safely assumed that weighing eyewitness testimony can be extremely difficult.

The legal field has attempted to grapple with eyewitness testimony by using the Braithwaithe test in criminal cases. The test is intended to provide the judge or jury with various factors to balance. Indeed, many of these factors coincide with the issues raised in social science research. Despite this, there are still enormous obstacles for fact-finders. First, gauging an individual’s memory is not an exact science. So many variables are in play that reliably establishing credibility is difficult. Second, judges and juries may come into trial with mistaken notions about the reliability of eyewitness testimony. Without training or knowledge of how memories work, fact-finders can frequently be swayed by faulty eyewitness testimony.

Despite these concerns, eyewitness testimony is still a crucial part of the criminal justice system - what better way to establish the circumstances of an event than to hear it from someone that witnessed it? As such, courts must learn how to grapple with eyewitness testimony in order to mitigate any prejudice that they may incite.

1. Committee on Scientific Approaches to Understanding and Maximizing the Validity and Reliability of Eyewitness Identification in Law Enforcement and the Courts et al., Identifying the Culprit: Assessing Eyewitness Identification (The Nat'l Academic Press 2014).

2. Eyewitness Misidentification

4. BENJAMIN N. CARDOZO, Reevaluating Lineups: Why Witnesses Make Mistakes and How to Reduce the Chance of Misidentification (AN INNOCENCE PROJECT REPORT 2009).

8. Manson v. Braithwaite, 432 U.S. 98 (1977). A law officer went to a suspected dealer and bought heroin from him, seeing him for about five minutes through a slightly open door. The officer was then presented with a photograph of the suspect hours later in his office. There was no line-up identification, but the photograph was introduced into evidence. The officer identified the man in the photograph as the dealer, and subsequently made an in-court identification, saying that there was no doubt that the Defendant was the dealer. The defendant was convicted.

The Supreme Court of the United States concluded that if there has been an unnecessarily suggestive investigative method, the admission of the identification into evidence then rests on the reliability of the evidence. The court then pointed to the opportunity of the witness to view the criminal at the time of the crime, the degree of attention paid by the witness, accuracy of the prior description, the time between the crime and the confrontation, and the witness’s certainty of the identification. (Factors originally identified in Neil v. Biggers, 409 U.S. at 188 (1972)) Thus, the main factor in determining the admissibility of identification testimony is reliability. The defendant’s conviction was affirmed.

9. Manson v. Brathwaite, 432 U.S. 98 (1977)

10. Perry v. New Hampshire, 132 S. Ct. 716 (2012). Barion Perry was convicted of breaking into a car in 2008. Witness Nubia Blandon stated to the Nashua, New Hampshire police department that she had observed Perry removing items from a parked car from her apartment window. Blandon was able to identify Perry at the scene, which led to his arrest. She was, however, unable to identify him at a subsequent photograph lineup, nor could she describe Perry to the police. Perry appealed his conviction. The Court, however, did not find that there was an unnecessarily suggestive investigative method by the police, and affirmed his conviction. It concluded that the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause of the Constitution of the United States does not require a court’s inquiry into the reliability of an eyewitness identification if the evidence was not obtained from unnecessarily suggestive law enforcement procedures.

12. Committee on Scientific Approaches to Understanding and Maximizing the Validity and Reliability of Eyewitness Identification in Law Enforcement and the Courts et al., Identifying the Culprit: Assessing Eyewitness Identification (The Nat'l Academic Press 2014).

21 State v. Henderson, 208 N.J. 208 (2011). Rodney Harper was killed in January 2003 in his Camden, New Jersey apartment. His acquaintance James Womble, was in Harper’s apartment celebrating the new year at the time of the shooting. Womble stated that two men came in, and one of them, George Clark, took Harper into a room and shot him, while his armed accomplice held Womble in a dark hallway. Womble was uncertain about making an identification of the accomplice when he was shown a photo lineup, but the police led him to believe that an identification needed to be made, after which he pointed to the defendant, Larry Henderson, as the culprit.

The Court reviewed modern Social Science empirical research on eyewitness identifications as part of the case. After reviewing the facts and the investigation procedures of this case, the Supreme Court of New Jersey concluded that the two-step Manson (See Manson v. Brathwaite, 432 U.S. 98 (1977)) legal standard for determining the admissibility of eyewitness identification did not in fact deter police misconduct, did not accurately determine the reliability of the evidence, and exaggerated the jury’s ability to appropriately assess eyewitness identification evidence as presented. As a revision of the standard, the court held that system and estimator variables should be taken into account at pretrial hearings at the mention of any evidence of suggestiveness by the defendant, and there should be specific jury instructions informing jury members about the science of eyewitness evidence, as well as relevant factors and their effects on reliability of the evidence. See Identification: In-Court Identification Only.

In Henderson, the Court found that the investigating officers unduly interrupted and encouraged the witness to make an identification out of the lineup, and the witness’s confidence in his identification was tainted by the unnecessary suggestiveness of the investigative procedure. The Court then remanded the case for an admissibility determination of the evidence per the new standard.

22. Elizabeth Loftus: The fiction of memory

23. Rick Permanand - 5 things a lawyer reveals were actually legal in "Making a Murderer".

24. Gina Vaynshteyn - Here's what's happened since "Making a Murderer" came out

25. BENJAMIN N. CARDOZO, Reevaluating Lineups: Why Witnesses Make Mistakes and How to Reduce the Chance of Misidentification (AN INNOCENCE PROJECT REPORT 2009).

29. BENJAMIN N. CARDOZO, Reevaluating Lineups: Why Witnesses Make Mistakes and How to Reduce the Chance of Misidentification (AN INNOCENCE PROJECT REPORT 2009); Committee on Scientific Approaches to Understanding and Maximizing the Validity and Reliability of Eyewitness Identification in Law Enforcement and the Courts et al., Identifying the Culprit: Assessing Eyewitness Identification (The Nat'l Academic Press 2014).

30. Model Policy and Procedure for Eyewitness Identification

31. Avery Bill finds legislative support