The Snitches that Deserve Stitches

Compiled by Chris Pantuso, Vadim Belinskiy, Hayden Rutledge, Lucas Lonergan, and Albert Hughes III

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, it is not uncommon for prosecutors to make deals with criminal informants in order to secure convictions of other criminal defendants.i In return for cooperation and substantial assistance from the informant, the prosecutor will be more lenient in trying the informant’s case, often dropping or reducing charges against them.ii “Jailhouse snitches” are commonly used as such informants, because they do not have to inform the defendant that the information conveyed to the snitch can be used against them, and occupy the same living space in jail with the defendant, and most importantly without the defendant’s attorney there to ensure the defendant does not divulge confidential information.iii However, a myriad of issues are intrinsic to the entire practice of using these snitches to assist in acquiring criminal convictions.iv As US Circuit Judge Stephen S. Trott has stated, “The most dangerous informer of all is the jailhouse snitch who claims another prisoner has confessed to him.”v

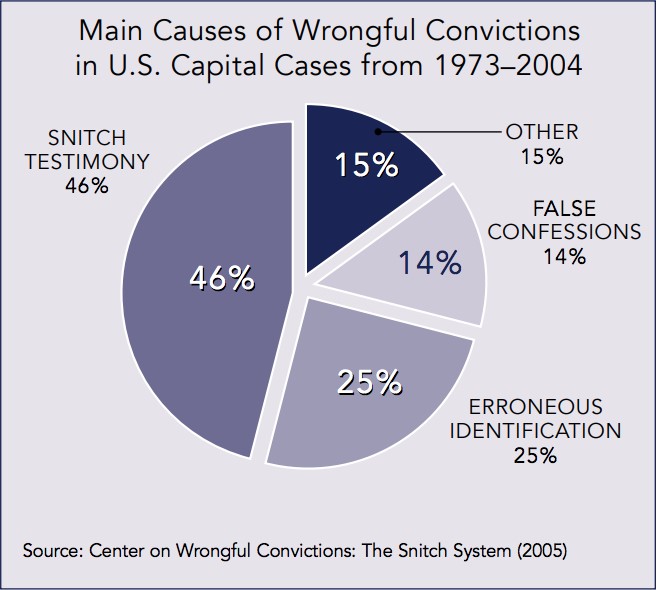

According to the Innocence Project, almost half of the death row exonerations since the 1970s have overturned the result of a case involving a jailhouse snitch.vi Additionally, a 2004 study found that “incentivized informant witnesses” are the leading cause of wrongful convictions in US Capital cases.vii This has brought suspicion to the entire practice of using jailhouse snitches’ testimony – can they be trusted when they have a strong incentive in claiming that the defendant has confessed incriminating information?viii As a result, three major issues have plagued the credibility of incentivized informant testimony: 1) allowing the informant to game the justice system by escaping punishment for their crimes, 2) the lack of disclosure to the parties in criminal trial as to what the informant’s incentives are, and 3) the possibility that unchecked jailhouse snitch testimony can lead to wrongful convictions of criminal defendants.ix

LEGAL STANDARD

Incentives: Although the most common incentive given to jailhouse snitches is a reduced sentence, there is little limit on what the United States can offer a jailhouse snitch in exchange for their testimony against another defendant. Although several Federal Circuit Courts have expressed hesitation at the use of snitches’ testimony, they have allowed leniency, money, food, and even drugs to be used as incentives.x

Disclosure: Although prosecutors are supposed to disclose information regarding a witness’s promise or agreement with the government because such information has been found to be exculpatory evidence,xi prosecutors have found a loophole to this requirement even where the information is material to the case. Prosecutors are not obligated to disclose incentive information if the criminal defendant accepts a plea deal. The Supreme Court in United States v. Ruiz declined to create a mandatory safeguard requiring pre-plea disclosures, and most circuit courts have also declined to do so. Because 97% of US criminal cases do not go to trial, this creates a disclosure exception for prosecutors in the majority of the cases they try.xii

Instruction Limits: The government is not allowed to instruct the informant as to whom to target and what to ask them, as this would make the informant an agent of the government. However, this is often circumvented by placing the informant in the same area as the defendant and telling them to “sit and listen” to what may be said.xiii

IN DEPTH LEGAL STANDARD AND CASE INFORMATION

The Supreme Court has constrained and defined the role of jailhouse informants through a few landmark cases over the past half-century.xiv These cases have been centered around the defendant’s 4th, 5th, and 6th amendment rights. In 1964, in Massiah v. United States, the court ruled that a defendant who has been charged with a crime has the right to have counsel present when being questioned by government agents.xv This case involved a man who, while out on bail, made incriminating statements to an associate who was cooperating with government agents. The associate allowed government agents to put a radio transmitter in his car so agents could listen inon their conversation. The court ruled that this was analogous enough to police interrogation that there was a right to have counsel present.

Just 2 years later in Hoffa v. United States, the court clarified that a government informant, deceptively placed into a defendant’s company, does not violate the defendant’s 4th, 5th, or 6th amendment rights when the defendant voluntarily associates with and gives information to the informant.xvi In this case, Edward Partin reported conversations he had with Jimmy Hoffa to federal law enforcement agents in return for payments to his wife and possibly for existing charges against him to be dropped. The federal government made clear that Partin had gone to see Hoffa on his own accord.

Compare the Hoffa case to United States v. Henry when in 1980, the Supreme Court ruled that statements made to a fellow inmate who had a prearranged agreement with a government agent to act as an informer were inadmissible.xvii Here, shortly after Henry was incarcerated agents working on a case against him contacted a former paid informant who happened to be serving time in the same jail. The agents told the informant that he was in the same cell block as multiple prisoners awaiting trial and to be alert for any statements made by them, but to not initiate conversation with Henry concerning his case. Once the informant was released from jail he recalled conversations with Henry to a government agent who then paid him. The court ruled that the conversations the informant had with Henry could not be used in court because of the prearranged deal and the fact that he stimulated conversation in order to get information.

Six years later in Kulhmann v. Wilson the court ruled that a jailhouse informant could be “placed in close proximity” to a defendant but could not make an effort to “stimulate conversations about the crime charged.”xviii In this case, Joseph Wilson was placed into the Bronx House of Detention in the same cell as Benny Lee who had agreed to be an informant. Wilson made incriminating statements to Lee without Lee asking any questions about the crime and simply listening to what Wilson had to say. The court determined that Lee’s statements were admissible and that Wilson’s rights were not violated because the informant did not take any action “designed deliberately to elicit incriminating remarks” besides merely listening.

The role of jailhouse informants was defined even more in 1990 when the Supreme Court ruled that an undercover agent could pose as a fellow inmate in a jail and ask suspects questions that could elicit an incriminating response without reading them their Miranda rights. In Illinois v. Perkins the police placed an undercover agent inside a jail cell with murder suspect Lloyd Perkins.xix The undercover agent was able to get Perkins totell him how he had murdered someone through asking if he had “done anybody.” The court ruled this information admissible because the situation of an undercover officer who the suspect believes to be a fellow cellmate lacks the typical coercive atmosphere present when a suspect knows they are being interrogated by the police.

THE SOCIAL SCIENCE OF JAILHOUSE SNITCHES

Numerous studies have identified eyewitness misidentification, flawed forensic science, false informant testimony, and false confessions as the four categories of evidence most frequently associated with wrongful convictions.xx However, while significant steps have been taken to address some of the other factors leading to wrongful convictions, in the context of informant testimony, progress in the realm of both policy and social science has seemingly lagged behind.xxi

A 2005 study by the Center for Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern School of Law examined 111 cases in which the defendants were exonerated from death row. The study found that in 51 of those 111 cases, the defendants were wrongfully sentenced to death based at least in part on the testimony of “witnesses with incentives to lie.”xxii

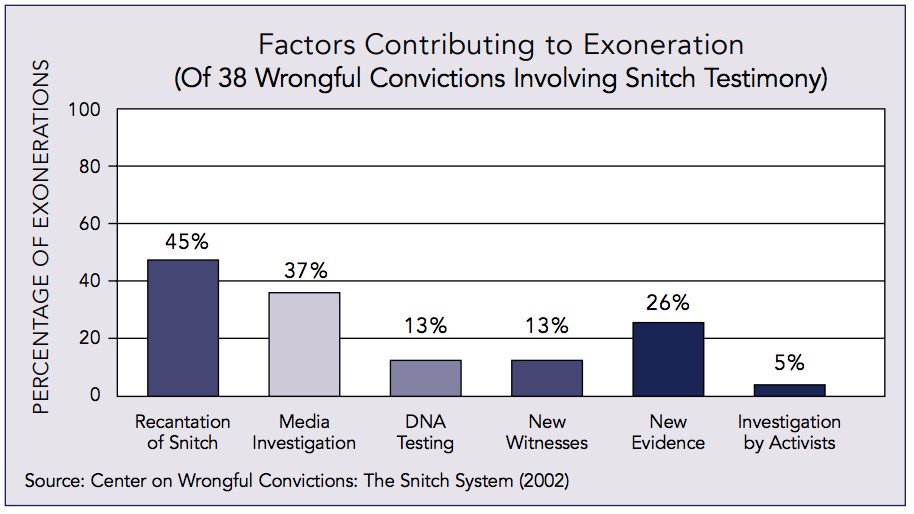

In a related 2002 study, the Center for Wrongful Convictions examined 97 cases in which evidence presented subsequent to sentencing conclusively exonerated the defendants. In 38 of those cases, informant witness testimony was shown to be a primary factor in the jury’s ultimate decision to convict the defendant. The study also revealed that, in 16 of those 97 cases, jailhouse snitches disclosed confessions that were never actually made by the defendant. That is, the confessions were entirely fabricated. In each such instance of a fabricated confession, the jailhouse snitch testifying on behalf of the government received some benefit in exchange for the testimony.xviii

Jailhouse snitches who testify as informants for the prosecution against a defendant often do so to obtain one or more varied incentives typically offered to them. The promise of improved jail conditions or the reduction of charges or jail sentences thus often serve as motivation for giving secondary confessions. As the Fifth Circuit has observed, “[i]t is difficult to imagine a greater motivation to lie than the inducement of a reduced sentence.”xxvi Additionally, the Fourth Circuit has noted that it was “obvious” that cooperation with the government, premised on lenience or immunity, “provide a strong inducement to falsify” testimony.xxvii

Psychological studies on the topic of incentives serving as motivations to lie appear to support these contentions. In 1996, Elizabeth Bruggeman and Kathleen Hart examined the incidence of lying for an incentive among a sample of high school students who attended either a religious or secular high school. After being tasked with memorizing a random sequence of numbers, the participant were instructed to replicate the pattern of numbers. As an incentive for the students, Bruggeman & Hart offered extra points on the semester grade of anyone who achieved a certain level of accuracy on the test. This threshold was set at level so high that it would be nearly impossible for the students to obtain. Additionally, they informed the participants that the test sheets would not be collected, and that the students only had to submit to the researchers the amount of overall correct numbers. Defining as a “liar” anyone who achieved the accuracy level needed to get the extra credit, Bruggeman & Hart found that 70% of the religious school students and 79% of the secular school students lied on the measure. The study concluded that an incentive, mixed with anonymity, was sufficient to induce high school students to lie. Further, that high school students would readily lie to gain a small amount of academic extra credit would suggest that criminals would readily lie for a reduced or commuted jail sentence.xxviii

Additionally, in 2010, Jessica Swanner, Denise Beike, and Alexander Cole tested whether incentives affect motivation for fabricating a secondary confession. In doing so, they utilized a variation of a computer crash paradigm developed by earlier by Saul Kassin and Katherine Kiechel. In Kassin & Kiechel’s study, participants performed a typing task in which they were instructed to not hit a certain key, as doing so would lead to a computer crash and loss of data. After the computer was programmed to automatically crash in the middle of the typing session, almost 70% of the participants in the study signed a confession admitting to pressing the forbidden key. The study demonstrated that, under the right amount of social pressure, individuals will confess to acts they may not have actually committed.xxix

Designing a variation of the Kassin & Kiechel study, Swanner, Beike, & Cole assigned each participants to either a “reader” or “typist” role. The reader was tasked with reading a string of numbers to the typist, while the typist was instructed to enter the string of numbers into a computer program. Both the readers and typists were cautioned to not hit the forbidden key, as doing so would similarly result in a crashing of the computer program. Again, the program was designed to automatically crash in the middle of the session. Half of the “reader” participants were offered the incentive of not having to attend a rescheduled session if they reported the typist’s admission. Swanner et al. found that 79% of the readers were willing to sign a statement indicating that the typist had pressed the forbidden key, which was significantly higher than the 52% of typists who admitted to causing the computer crash. Providing the incentive to the readers saw the signing rate of the statements to nearly 100%.xxx

EASE OF OFFERING JAILHOUSE SNITCH TESTIMONY

Not only are the incentives for jailhouse snitches to manufacture false testimony powerful, but the reality is that difficulty of doing so is minimal. To generate a credible confession, jailhouse snitches only need to learn basic details about a fellow inmate’s case. Snitches need only to speak with complicit friends and relatives who are able to monitor case proceedings and details from outside of jail. Additionally, given the pervasiveness of the internet, snitches can easily fabricate secondary confessions based upon extensive and detailed case specifics. This combination of increasingly available information over the internet and increasing inmate internet access “makes fabricating confessions even easier than ever before.”xxxi Moreover, jailhouse snitches risk little by fabricating false testimonies. According to The Justice Project, perjury prosecutions of jailhouse snitches giving false testimonies are almost nonexistent.xxxii The reality is that lying jailhouse snitches have everything to gain and almost nothing to lose by falsely reporting to the government and testifying to juries that fellow inmates have confessed to crimes.

The incentives for jailhouse snitches to offer testimony against their fellow inmates are so great, and the costs of using such secondary confessions are so low, that prosecutors frequently put such jailhouse snitches on the stand despite multiple red flags. Confirmation bias and tunnel vision are significant explanations for the astounding frequency with which jailhouse snitch testimony, that is subsequently proven false, is accepted and utilized by prosecutors. Confirmation bias is described by cognitive researchers as the well-documented tendency for individuals to seek out evidence that confirms their pre-existing beliefs while downplaying or outright ignoring evidence that contradicts those beliefs.xxxiii Similarly, tunnel vision refers to the tendency of persons to ignore or downplay evidence inconsistent with that individual’s pre-existing beliefs.xxxiv Prosecutorial tunnel vision, which has often on its own been identified as a major cause of wrongful criminal convictions, coupled with confirmation bias can help explain why prosecutors seem so willing to continue to defend the credibility of jailhouse snitch testimony even after it has been confirmed in exoneration proceedings to have been false.xxxv

SOCIAL SCIENCE AND THE FLOWERS CASE

In 1996, 4 employees of Tardy Furniture Store in Mississippi were killed during a robbery.xxxvi The top prosecutor, Doug Evans, has charged the store’s former employee Curtis Flowers with murder.xxxvii Prior to this incident, Flowers had no prior convictions for crime -- because of this incident, Flowers has been on trial 6 times for the same incident.xxxviii Six trials! xxxix The first three trials, of which resulted in convictions for Flowers, were thrown out by the Mississippi Supreme Court.xl The first two times were due to misconduct by Evans and the third time was due to Evans keeping African-Americans off the jury -- which offends the 6th amendment guarantee to be tried by a jury of one’s peers.xli The fourth and fifth trial had multiple black jurors and did not result in a conviction.xliiThe sixth trial had only one black juror and ended in a conviction for all four murders.xliii

Flowers appealed his conviction for multiple reasons, including that his 6th and 14th amendment rights were violated due to Evans exercising the prosecution’s peremptory strikes for the jury selection process in a racially discriminatory way.xliv Evans had struck five prospective jurors during the sixth trial.xlv The trial and appellate courts rejected Flowers’s argument; the Supreme Court has granted certiorari as to whether the Mississippi Supreme Court has erred in applying precedent regarding discrimination in jury selection.xlvi

Jailhouse snitch testimony was key in convicting Flowers initially. Flowers was tried for the first time in 1997, where Evans obtained information from Flowers’s cellmates to convict Flowers.xlvii “None of the witnesses who came forward were credible… They were all compromised and fearful.”xlviii Flowers’s cellmates Frederick Veal and Maurice Hawkins both testified that Flowers had admitted to the crimes.xlix According to court documents Veal later claimed that he was elicited by Evans with a piece of paper telling him what happened in the case.l Hawkins and Veal both later signed a sworn affidavit saying that their testimony was false.li Subsequently, Evans had to rely on another jailhouse snitch, Odell Hallmon, in order to convict Flowers.lii Odell Hallmon’s sister claimed that she saw Flowers in a pair of the same shoes that left a footprint at the scene of the crime, however, Odell Hallmon claimed that she was lying so that she would get the reward money.liii Odell Hallmon later changed sides and said that Flowers had confessed to him that Flowers committed the murders.liv Hallmon had two drug charges dropped because of his testimony. Hallmon later confessed that he lied because Evans agreed to drop some charges against Hallmon.lv Multiple red flags (such as the wavering testimony) were there for the snitches that were used, and still yet, the prosecution proceeded forward with their case. With all the jailhouse snitches admitting to lying, this greatly calls into question at least two things: Flowers’s guilt and the ability to use jailhouse snitches because of their desire to reduce their personal sentences.

CONCLUSION

Social science studies on issues relating to jailhouse snitches reveal that incentivized informants often provide low quality or false testimony in order to benefit themselves. Not only is the threshold for informants toredeem these benefits incredibly low, the practices employed by informants are often invasive and shakily regulated as demonstrated by current case law. Furthermore, several studies have shown us that incentives can easily lead to fabricated testimony. The potential dangers of jailhouse snitches are realized in the case of Curtis Flowers. Originally, two jailhouse informants testified that Flowers told them he had committed the murders. Yearslater, both informants have recanted and now claim that the confessions were falsified. But the damage has already been done because their supposedly false testimony was used to villainize Mr. Flowers.

While the current social science studies expose many of the issues and dangers underlying jailhouse snitch testimony, there is an apparent lack of studies geared specifically toward examining the relationships between snitches, incentives and false testimony. Much of the social science deals with these issues individually, but studies that clearly link these studies’ conclusions together would likely be useful in changing the trial practice landscape and preventing cases such as Flowers’.

Despite the glaring issues shown above, jailhouse snitches will still be used to falsely convict hundreds of people in the coming years and there is little indication in case law that the situation will improve. However, through the expansion of social science on the topic and greater reliance on already demonstrated conclusions, there is a glimmer of hope that cases like Flowers’ will be prevented in the future.

Footnote Resources:

i The Marshall Project, The Jailhouse Snitch Quiz, April 4, 2018.

iii Paul C. Giannelli, Brady and Jailhouse Snitches, Case Western Faculty Publications, 2007 F.B. 151.

iv Markus Surratt, Comment: Incentivized Informants, Brady, Ruiz, and Wrongful Imprisonment: Requiring Pre-Plea Disclosure of Material Exculpatory Evidence, 93 Wash. L. Rev. 523 (2018).

v Stephen S. Trott, Words of Warning for Prosecutors Using Criminals as Witnesses, 47 HASTINGS L.J. 1381, 1394 (1996).

vi Paul C. Giannelli, Brady and Jailhouse Snitches, Case Western Faculty Publications, 2007 F.B. 151.

vii The Innocence Project, Safeguarding Against Unreliable Jailhouse Informant Testimony.

viii Markus Surratt, Comment: Incentivized Informants, Brady, Ruiz, and Wrongful Imprisonment: Requiring Pre-Plea Disclosure of Material Exculpatory Evidence, 93 Wash. L. Rev. 523 (2018).

xi Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963); Giglio v. United States, 405 U.S. 150 (1973).

xii Markus Surratt, Comment: Incentivized Informants, Brady, Ruiz, and Wrongful Imprisonment: Requiring Pre-Plea Disclosure of Material Exculpatory Evidence, 93 Wash. L. Rev. 523 (2018).

xiii The Marshall Project, The Jailhouse Snitch Quiz, April 4, 2018.

xiv Natapoff, Alexandra. “The Shadowy World of Jailhouse Informants: Explained.” The Appeal, 11 July 2018.

xv Massiah v. United States, 377 U.S. 201 (1964).

xvi Hoffa v. United States, 385 U.S. 293 (1966).

xvii United States v. Henry, 447 U.S. 264 (1980).

xviii Kuhlmann v. Wilson, 477 U.S. 436 (1986).

xix Illinois v. Perkins, 496 U.S. 292 (1990).

xx Jessica A. Roth, Informant Witnesses and the Risk of Wrongful Convictions, 53 Am. Crim. L. Rev. 737, 738 (2016).

xxii Center on Wrongful Convictions, The Snitch System: How Snitch Testimony Sent Randy Steidl and other Innocent Americans to Death Row.

xxiii The Justice Project, Jailhouse Snitch Testimony: A Policy Review, The Pew Charitable Trusts 1 (2007).

xxiv Rob Warden, The Snitch System: How Incentivised Witnesses Put 38 Innocent Americans on Death Row. Research Paper, Arizona State University College of Law, Tempe, AZ, April 25, 2002.

xxv The Justice Project, Jailhouse Snitch Testimony: A Policy Review.

xxvi Russell D. Covey, Abolishing Jailhouse Snitch Testimony 49 Wake Forest L. Rev. 1375 (2014) (citing United States v. Cervantes-Pacheco, 826 F.2d 310, 315 (5th Cir. 1987)).

xxvii Id. (citing United States v. Meinster, 619 F.2d 1041, 1045 (4th Cir. 1980)).

xxviii Jeffrey S. Neuschatz, Nicholaus Jones, & Joy McClung, Unreliable Informant Testimony, Conviction of the Innocent: Lessons from Psychological Research (2012) (citing Elizabeth Leistler Bruggeman & Kathleen J. Hart, Cheating, Lying, and Moral Reasoning by Religious and Secular High School Students, 89 The Journal of Education Research 340—44 (1996)).

xxix Id. (citing Saul M. Kassin & Katherine L. Kiechel, The Social Psychology of False Confessions: Compliance, Internalization, and Confabulation, 7(3) Psychological Science 125—28 (1996)).

xxx Id. (citing Jessica K. Swanner, Denise R. Beike, & Alexander T. Cole, Snitching, Lies and Computer Crashes: An Experimental Investigation of Secondary Confessions, 34 Law and Human Behavior 53—65 (2010)).

xxxi Russell D. Covey, Abolishing Jailhouse Snitch Testimony 49 WAKE FOREST L. REV. 1375 (2014) (citing Peter P. Handy, Jailhouse Informants’ Testimony Gets Scrutiny Commensurate with Its Reliability, 43 MCGEORGE L. REV. 755, 759 (2012)).

xxxii THE JUSTICE PROJECT, Jailhouse Snitch Testimony: A Policy Review, THE PEW CHARITABLE TRUSTS 8—9 (2007).

xxxiii Raymond S. Nickerson, Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises, 2 REV. GEN. PSYCHOL. 175 (1998); Barbara O'Brien, Prime Suspect: An Examination of Factors that Aggravate and Counteract Confirmation Bias in Criminal Investigations, 15 PSYCHOL. PUB. POL'Y & L. 315 (2009).

xxxiv Barbara O'Brien, A Recipe for Bias: An Empirical Look at the Interplay Between Institutional Incentives and Bounded Rationality in Prosecutorial Decision Making, 74 MO. L. REV. 999, 1044 (2009).

xxxv Russell D. Covey, Abolishing Jailhouse Snitch Testimony 49 WAKE FOREST L. REV. 1375 (2014) (citing Charles I. Lugosi, Punishing the Factually Innocent: DNA, Habeas Corpus And Justice, 12 GEO. MASON U. C.R. L.J. 233, 235 (2002)).

xxxvi Flowers v. Mississippi, OYEZ, March 10, 2019.

xxxvii Leonhardt, The Mississippi Man Tried Six Times for the Same Crime, May 20, 2018, The New York Times.

xlvii Baptiste, Prosecutors are Using Jailhouse Snitches to Send Innocent People to Death Row, July 9, 2018, Mother Jones.