Race-Based Peremptory Challenges

Compiled by Nathalie Greenfield, David Eichert, Nicholas Pulakos, and Oladoyin Olanrewaju

Introduction

The question before the Supreme Court of the United States in Flowers v. Mississippi is as follows: did the Mississippi Supreme Court err in how it applied Batson v. Kentucky in Curtis Flowers’ most recent appeal? Batson v. Kentucky declared unconstitutional the use of racial discrimination in peremptory challenges. At the heart of Flowers is thus the question of whether DA Doug Evans’ striking of black jurors was impermissible racial discrimination under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Legal issue: peremptory challenges

The critical case regarding peremptory challenges is Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986). Batson established that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment forbids prosecutors from exercising their peremptory challenges to strike potential jurors solely on account of their race. The Court outlined a three-step balancing test to determine if a prosecutor has exercised a peremptory challenge is a racially impermissible manner:

- The defendant must first make a prima facie case showing that she belongs to a cognizable racial group and that the prosecutor exercised peremptory challenges on the basis of race.

- In response, the prosecutor must articulate a race-neutral reason for striking the juror in question.

- The court is then required to determine whether the defendant carried her burden of proving purposeful discrimination.

Soon after Batson, the Court affirmed Batson’s holding and further held that racial classifications remain impermissible when they are visited upon all persons, irrespective of race. Powers v. Ohio, 499 U.S. 400 (1991) at 410. Subsequent cases have modified the Batson holding and provide some clarity of how Batson violations are analyzed.

The bar for establishing a Batson violation is high, as the prosecutor’s proffered reason for striking a juror is presumptively race-neutral. Over the years, courts have defined certain circumstances that can come to bear on the analysis of a Batson violation. Some circuits have held that, when analyzing Batson challenges, courts should examine side-by-side comparisons of black venire panelists who were struck and white panelists allowed to serve. See, e.g., Chamberlin v. Fisher, 885 F.3d 657 (5th Cir. 2017) at 665. Indeed, if a prosecutor’s proffered reason for striking a black panelist applies just as well to an otherwise-similar nonblack panelist who is not struck, that can be persuasive evidence of a Batson violation. Foster v. Chatman, 136 S.Ct. 1737 (2016). A trial court deciding a Batson violation must also consider all of the circumstances that bear upon the issue of purposeful discrimination, including - among others - the striking party’s demeanor, the prosepctive juror’s demeanor, the plausibility of the explanations, and whether the proffered rationale has a basis in accepted trial strategy. Snyder v. Louisiana, 552, U.S. 472 (2008) at 477; People v. Beauvais, 393 P.3d 509 (2017) at 517. Appellate courts review trial judges’ findings of Batson violations under a highly deferential standard. Snyder at 479 .

To illustrate, in Foster, the court found that the prosecutor had engaged in impermissible racial discrimination in striking two prospective black jurors. In noting the evidence that pointed to a Batson violation, the court explained that the State gave shifting explanations for the strike, the State misrepresented the record, and there was a persistent focus in the prosecutor’s file on race, including the placement of the letter ‘B’ next to each black prospective juror’s name.

Flowers v. State

The Supreme Court of Mississippi on appeal of Flowers VI decided that the trial court did not err in accepting the prosecution’s peremptory strikes and denying Flower’s Batson challenge. Flowers v. Miss., 240 So.3d 1082, 1116-35 (2017). During jury selection of Flowers VI, DA Evans exercised peremptory strikes for six jurors, after accepting the first black juror. Id. at 1122. The trial court found a prima facie case of discrimination because five of the six jurors struck were black, which was ultimately denied. Id. On appeal, the defense asked the Supreme Court of Mississippi to review the trial court’s rejection of the Batson challenge. Id.

The Court rejected Flower’s argument that Doug Evans’ previous Batson violations constituted “exceptional circumstances,” therefore should have been included in the trial court’s Batson analysis. Id. at 1135. Evans previously used racially discriminatory jury selection in Flowers II & III. At Flowers II, one of Evans’ strikes was removed because it was found to be racially motivated. Id. at 1117. On appeal of Flowers III, the court held Batson was violated when the trial court allowed peremptory strikes of two jurors, despite signs of racial discriminatory purpose. Id. Flower’s claimed that Evans’ history of Batson violations should have been considered in the trial court’s evaluation, following the Supreme Court’s analysis in Foster v. Chatham, 136 S.Ct. 1737 (2016) and Miller-El v. Dretke, 545 U.S. 231 (2005). Id. at 1122. The Supreme Court of Mississippi rejected this argument because the race neutral explanation of peremptory strikes in Flower VI were sufficient in light of the trial court’s factual findings, and Evans’ past violations are not as “despicable” as the circumstances of Foster, nor as explicitly detailed as the policy in Miller-El. Id. at 1123-24.

Flowers claimed the prosecution used peremptory strikes in a racially discriminatory way by the disparate questioning of black jurors, by responding differently to voir dire answers from black jurors, and by mischaracterizing the black jurors’ responses to voir dire answers. Id. at 1124. The Court rejected each of these claims. Id. at 1135. The defense argued that black jurors answered more questions than white jurors, which the state acknowledged as a possible sign of discrimination but concluded that “[D]isparate questioning is not dispositive of racial discrimination.” Id. at 1125. Further, the court found that each of the prosecution’s race neutral reasons for striking the five black jurors were well represented by the evidence. Id. at 1135. The defense argued that many of the race neutral reasons were applicable to white jurors who had not been struck. Id. at 1126-35 (arguing in favor of the prosecution’s facially neutral reasons for all five black panelists struck). The Court relied on various distinctions to qualify the prosecutions’ reasons, thus rejecting Flowers’ claims of discriminatory treatment to black jurors. Id. at 1135.

Petitioner's Brief for Flowers v. Mississippi

The analysis within the petitioner’s brief begins by arguing that the Court ignored Evans’ history of discrimination within the previous Flowers cases. Brief for Petitioner at 24, Flowers v. Miss., appeal docketed, (2018) (No. 17-952). In ignoring this history, Evans was able to “conceal” discrimination by creating a weaker prima facie case to pass the Supreme Court of Mississippi’s review. Id. at 25. The petitioner developed this reasoning by juxtaposing the violations of Flowers III with what the Mississippi Court approved in Flowers VI. Id. at 25-26. For example, in Flowers III, Evans struck 15 possible black panelists, while in Flowers VI, a black panelist was accepted before striking five other black panelists. Id. at 25. Also, in previous Flowers cases, the court approved strikes for “acquaintance with the Flower’s family,” thus Evans heavily questioned black panelist for relationship information, but not white panelist. Id. The petitioner argues that by acknowledging Evans’ actions within the history of the Flowers cases, the “hallmarks of a prosecutor still bent on seating as few black jurors as possible” is revealed. Id. at 26.

Social science and peremptory challenges

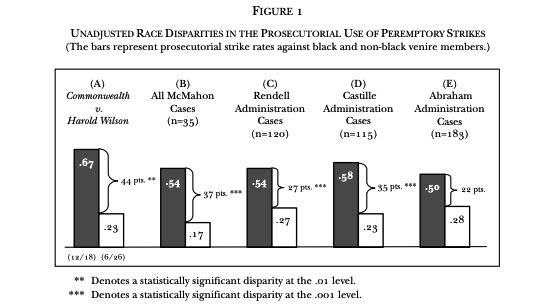

Post-Batson case decisions have been described as “indeterminate, unprincipled, and ineffective.1 One aspect that has led to these problems is the legal ambiguity concerning evidentiary framework that is necessary for a proper understanding of empirical results in Batson cases. Later Supreme Court cases laid parameters that helped courts apply the proper understanding to subsequent Batson cases. A study created by David Baldus, focuses on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court case, Commonwealth v. Harold Wilson, which successfully argued for dismissal of a Batson-like claim by using statistical evidence and Supreme Court guidance. The evidence compared the use of peremptory strikes in Wilson with the use of peremptory strikes by previous district attorneys.

To mitigate the chance that alternative controls could be responsible for the study's outcome, the following factors were considered: different District Attorney administrations, venire member race, gender, age, occupation, education, race of the defendant, race of the victim, level of poverty and median income for the venire-member’s neighborhood. Each control was individually introduced. The study’s results still had the same conclusion: that race was a determinative factor in peremptory challenges. Taking the study into account, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ordered for a retrial.

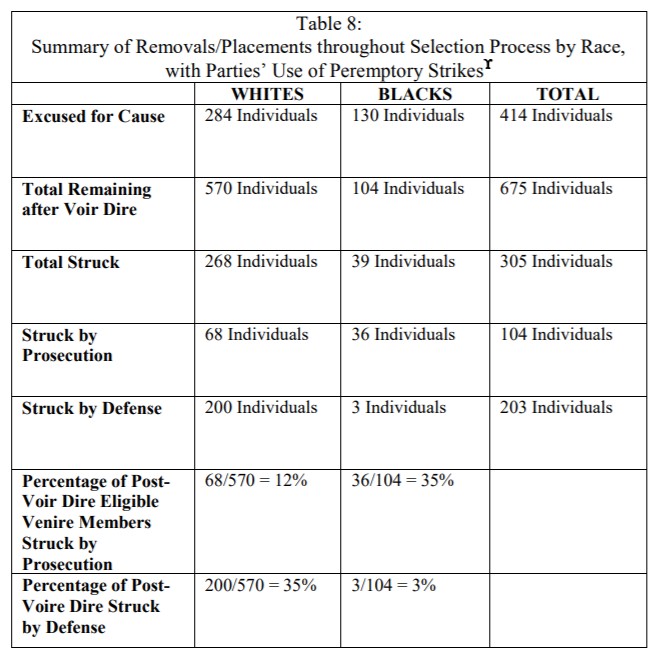

A study by Ann Eisenberg used trial transcripts to examine the race-based exclusion of potential jurors during several stages of jury selection in a set of 35 South Carolina cases which resulted in death sentences between 1997 to 2012.2 Eisenberg found that prosecutors used peremptory strikes against 35% of eligible African-American venire members, compared to 12% of eligible white venire members. Eisenberg also demonstrates how her study corresponds with many other studies which demonstrate that the peremptory challenge process impeded a significant number of African-Americans from serving on juries.

Another study which demonstrated how race-based peremptory challenges could avoid a Batson Challenge and exclude African-Americans from jury participation was conducted by Samuel Sommers and Michael Norton.3 The authors recruited three groups of college students, law students, and attorneys who participated in a mock jury selection process. Across all three samples, the authors found that a prospective juror’s race does indeed influence peremptory challenge use; moreover, when justifying their peremptory challenge use, participants rarely cited race as an influential factor, instead claiming racially neutral reasons for their use of peremptory challenges. As such, the authors conclude that the use of Batson Challenges is flawed, since prosecutors can and likely do use race-neutral reasons to excuse their racially-biased peremptory challenges.

Bias in Jury Selection: Justifying Prohibited Peremptory Challenges, by Michael I. Norton, Samuel R. Sommers, and Sara Brauner, discusses how attorneys’ desire to select jurors favorable to their case may bias their decision-making. The study they conducted considered the trial of a female defendant accused of murdering her abusive husband, and asked individuals playing the role of prosecutor to choose to excuse either a male or female juror. As the researchers predicted, participants excused female jurors more frequently than otherwise identical male jurors. Participants were also likely to generate gender-neutral reasons for their decisions. This study primarily used students who may not have been aware of the prohibition on the use of race and gender in excusing potential jurors.

In a follow-up study, where participants were told they could not consider gender, participants provided longer explanations for their decisions. The researchers suggested that by providing additional information to justify their decisions, participants who challenged a female juror despite an explicit warning not to consider gender, may be even more persuasive in their effort to explain their peremptory use in gender-neutral terms. Rose (1999) observed jury selection proceedings for 13 criminal trials, 12 of these proceedings had an African American defendant, and found that prosecutors were more likely to challenge African American jurors while defense attorneys were more likely to challenge White jurors. These results cast doubt on the practical effectiveness of current restrictions placed on peremptory use.

Conclusion

As demonstrated by this small sample of scientific studies about race in peremptory challenges, social science strongly suggests that the prosecution’s use of peremptory challenges in Flowers was motivated by a desire to remove African-Americans from the jury.

Footnote Resources:

1 David C. Baldus, Statistical Proof of Racial Discrimination in the Use of Peremptory Challenges: The Impact and Promise of the Miller-El Line of Cases As Reflected in the Experience of One Philadelphia Capital Case, Michigan State University College of Law Journal (2012).

2 Ann M. Eisenberg, Removal of Women and African-Americans in Jury Selection in South Carolina Capital Cases, 1997-2012, Northeastern University Law Journal 1 (2016). empe

3 Samuel R. Sommers and Michael I. Norton, Race-Based Judgments, Race-Neutral Justifications: Experimental Examination of Peremptory Use and the Batson Challenge Procedure, 31 Law Hum Behav 261 (2007).