Additional resources:

-

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., Inc., 529 U.S. 205 (2000).

-

Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co., Inc., 514 U.S. 159 (1995).

-

TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Marketing Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23 (2001).

-

Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., 678 F.3d 1314 (2012).

-

New York Times – Jury Awards $1 Billion to Apple in Samsung Patent Case

-

Demonstrative Evidence and Storytelling: Lessons from Apple v. Samsung

-

Patent Litigation Graphics + Storytelling Proven Effective: The Apple v. Samsung Jury Speaks

-

Federal Circuit Offers Apple Second Chance to Block Sales of Samsung Galaxy Nexus Devices

-

Nekane Balluerka, The Influence of Instructions, Outlines, and Illustrations on the Comprehension and Recall of Scientific Texts, 20 Comtemp. Educ. Psychol. 369-70 (1995).

-

Firoz Dattu, Illustrated Jury Instructions: A Proposal, 22 Law & Psychol. Rev. 67 (1998) (discussing the importance of visual aids for jurors).

-

Falk et al., From Neural Responses to Population Behavior, Psychological Science (April 2012).

Two Pesos v. Cabana

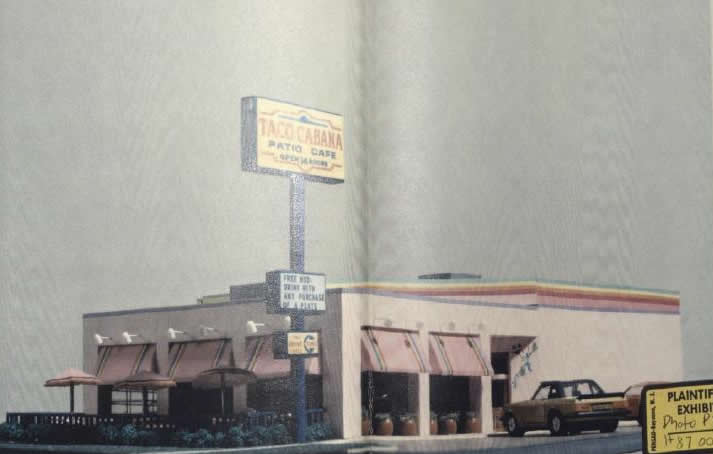

In 1978, Taco Cabana opened a restaurant in San Antonio, Texas, with Mexican trade dress. By 1985, Taco Cabana opened 5 more in San Antonio. In 1985, in Houston, Texas, another restaurant with similar motifs opened under the name of Two Pesos, and started to open new restaurants aggressively in and out of Texas, but not in San Antonio. In 1986, Taco Cabana expanded into other cities where Two Pesos had restaurants, and sued Two Pesos for trade dress infringement.

[Fig.1] Taco Cabana and Two Pesos: exteriors

At issue were what constitutes trade dress and what requirements for trade dress are. Presented with dueling surveys from each party, the jury found that Two Pesos infringed Taco Cabana’s trade dress within the meaning of Lanham Act because Two Pesos restaurants created a likelihood of confusion to ordinary customers. The district court ordered Two Pesos to pay the total damage award over $2 million plus $1 million attorney’s fees.1 The district court also ordered Two Pesos to remove elements that resemble Taco Cabana. Two Pesos appealed up to the Supreme Court.

A. Definition of Trade Dress: Expert Testimony

Both parties hotly debated the definition of trade dress. To be protected by the Lanham Act, trade dress must be inherently distinctive and non-functional. Otherwise, trade dress must have acquired a secondary meaning. Taco Cabana claimed that their trade dress was:

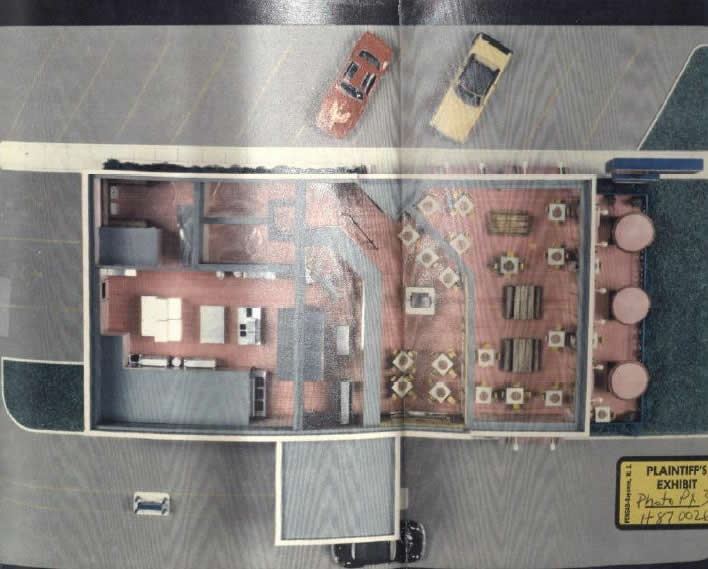

| "a festive eating atmosphere having interior dining and patio areas decorated with artifacts, bright colors, paintings and murals. The patio includes interior and exterior areas with the interior patio capable of being sealed off from the outside patio by overhead garage doors. The stepped exterior of the building is a festive and vivid color scheme using top border paint and neon stripes. Bright awnings and umbrellas continue the theme."2 |

To argue that such a broad and inclusive conception constitutes "trade dress" within the meaning of Lanham Act, Taco Cabana offered testimony from its owner, employees and industry experts. The owner testified that their trade dress must be protected because of its originality. "It’s an original concept. There’s nothing like it anywhere. … It’s a cross between Taco Bell, which is a very plastic concept, and a traditional sit-down restaurant."3 One of the experts, Mr. Brinker, provided a more nuanced explanation that the exterior and interior of Taco Cabana restaurants, as a whole, created "an experience" with business ramifications.4

| "But those restaurants that are really successful, it has something else about it. It’s a place where you feel comfortable. … And when I leave … my total experience is well worth the amount of money that I’ve paid for that experience. … Well, trade dress is the total concept or precept that you experience. It’s the method of service, the ambiance. It’s the way the employees look. It’s how the food is delivered. It’s how the food is prepared. It’s the palatalizing of the food. And certainly the location. Color."5 |

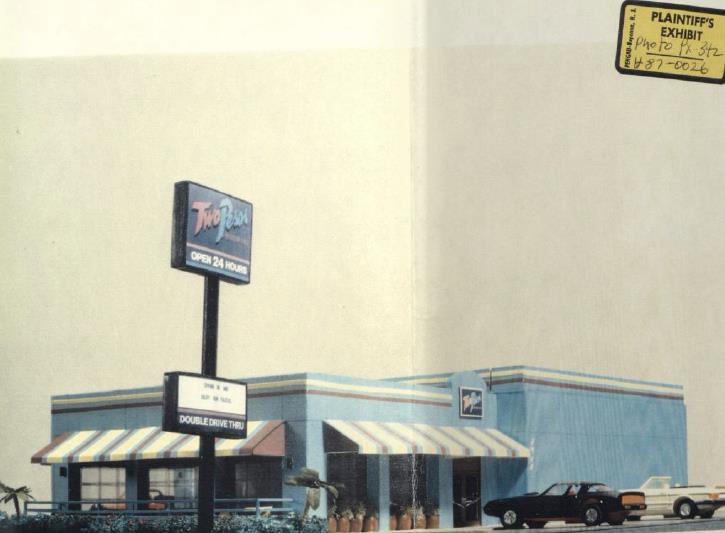

[Fig.2] Taco Cabana and Two Pesos: floor plans

| He also commented on the traffic control of Taco Cabana's interior design:

"A: The traffic, of course, was just incredible. As a matter of fact, the volume they were doing was, oh, 50 to 60 percent more approximately in an average volume than McDonald’s with about the same square footage. I was really quite impressed. …

Q: Well, what made you think trade dress was so remarkable other than the fact that heavy traffic came through? A: Well, you know, in this business, you can’t separate out any one thing, as I mentioned before. It’s a total of everything. …"6 |

[Fig.3] Taco Cabana and Two Pesos: interiors

In response, Two Pesos claimed that first, Taco Cabana’s trade dress fails to pass the functionality test because "individual elements … are functional," and second, "Taco Cabana’s trade dress is not distinctive … [and] geographically descriptive."7 Thus, it is not protectable by the law. During discovery and testimony, Two Pesos obtained similar statements from both parties’ witnesses. Even the Taco Cabana owner agreed:

| "Q: Do you agree with Mr. Brinker that the only nonfunctional items are décor and plants?

A: Pretty well, I’d say. Q: Is the answer yes? A: Yes."8 |

Two Pesos also argued that the dissimilarities of the color schemes and names are dispositive, but Mr. Brinker disagreed:

| "Q: Now, taking the blue one or looking at the outside profiles of these various restaurants, do you have an opinion as to the similarities or differences of them? …

A: If you excluded the name, you simply couldn’t tell because you have different colors already. You’ve lost identification … [a consumer] wouldn’t know where he was. … You have that confusion. … Q: Now, the argument has been made that the name is enough to make a difference. Do you have an opinion on that? A: You know, it’s an interesting phenomenon. I haven’t ever seen anything quite like this in my experience where the ambience and the concept, the patio concept, the dominance or predominance of the opening doors or of the patio has overshadowed the name. …"9 |

It appears that Taco Cabana’s expert testimony impressed the court. In the jury instruction, Judge Singleton in the Southern District of Texas stated that trade dress is "total image of the business. Taco Cabana's trade dress may include the shape and general appearance of the exterior of the restaurant, the identifying sign, the interior kitchen floor plan, the decor, the menu, the equipment used to serve food, the servers' uniform and other features reflecting the total image of the restaurant." At the appellate level, Two Pesos challenged the jury instruction because such definition is too broad. However, siding with the district court, the Fifth Circuit held that the jury instruction was proper and found that trade dress can be "a combination of visual elements that, taken together, … may create a distinctive visual impression."10 Thus, a whole can be qualitatively different from the sum of parts. Even when parts are functional, the combination as a whole can be non-functional. The existence of descriptive parts "does not eliminate the possibility of inherent distinctiveness" as a whole.

B. Likelihood of Confusion: Dueling Surveys, and Interpretations thereof

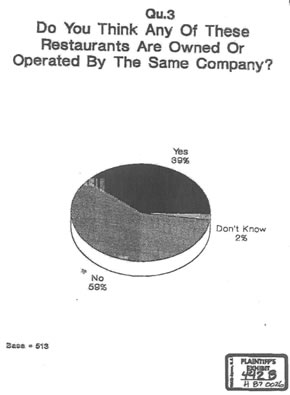

To prove likelihood of confusion, Taco Cabana introduced survey data performed by Mr. Gelb ("Gelb survey"). The Gelb survey respondents were customers of Taco Cabana and Ta Casita,11 and were asked four questions: (Q1) Have you ever been to a Ta Casita, or Taco Cabana or Two Pesos Restaurant? (Q2) If yes, Which ones? (Q3) Do you think that any of these stores are owned and operated by the same company? (Q4) If yes, Why do you say that?

| Q1 is a screening question to select customers that have been both Taco Cabana and Two Pesos. Fig.4 shows that there are overlaps in the clientele for each restaurant. However, since some respondents may have only visited Taco Cabana and Ta Casita, but not Two Pesos, the study’s conclusion with regard to confusion between Taco Cabana and Two Pesos may not be as sweeping as it suggested. Also, the Gelb survey did not provide the number of drop-outs, while the base number for the rest of the questions, 513, is quite high. |

[Fig.4] Gelb Survey: Which ones have you eaten at? |

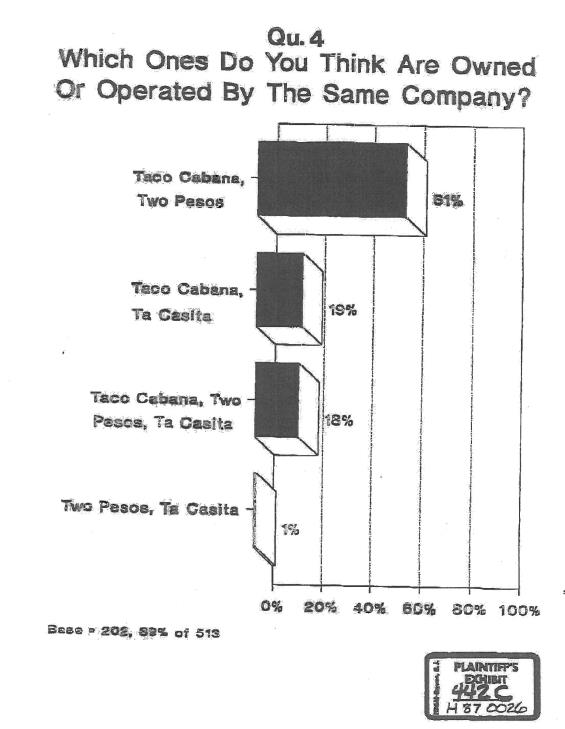

Fig.5 is a response set for Q3 from which Gelb concluded that the rate of confusion between Taco Cabana and Two Pesos was 31%.12 For 39% who thought Two Pesos and Taco Cabana were co-owned or co-operated, Gelb asked another question "Which ones do you think are owned or operated by the same company?" (Fig.5). 61% said Taco Cabana and Two Pesos were sister companies, 19% said Taco Cabana and Ta Casita were, and 18% said all three were (Fig.6). Gelb then combined 61% and 18% to get the total percentage of people who were confused "about the operation of the two, or three, restaurants," and multiplied that percentage, 79%, by 39% (who answered "Yes" in Fig.5) to obtain "the total sample who seemed to be confused." However, note that such computation, lumping up the percentage of people who were confused about the two and the three restaurants, may not lead to the correct rate of confusion among these three restaurants. First, from the outward appearance, Taco Cabana and Ta Casita were essentially identical, andsecond, Ta Casita had been operating in the market only for a short period of time.

|

|

| [Fig.5] Gelb Survery: Consumer opinions about co-ownership | [Fig.6] Gelb Survery: Consumer opinions about co-ownership - detailed opinions |

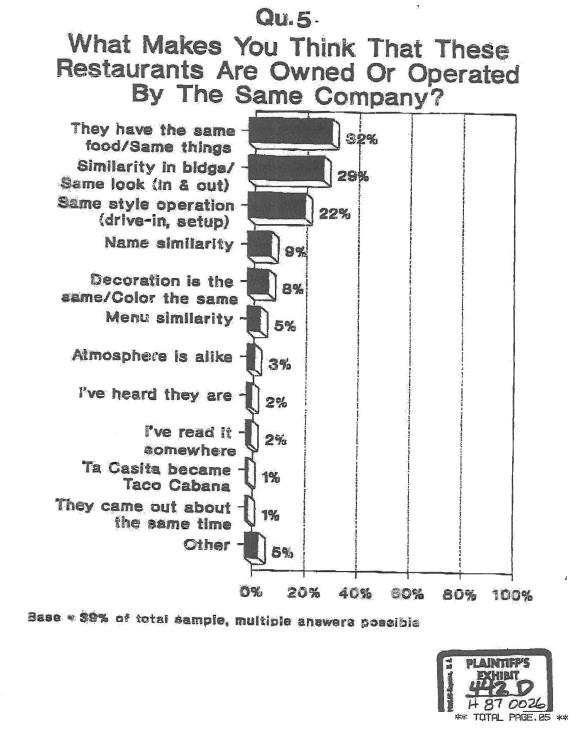

Fig.7 is a list-up of all the various answers to Q4. As Q4 is an open question, the answers were so varied that Gelb created categories to place the responses under. Note that the responses could be classified into more than one category because often one response may have several references. "Some people say, ‘Well, the building looks the same. That’s why I think that they’re owned or operated by the same company,’ or they might say, ‘Well, the menu is the same also.’ So they could be represented in more than one of those [categories]."13 Understanding trade dress as uniqueness or originality of concept in operating a restaurant, Gelb testified that "All of those answers above the 3 percent seem to be Trade Dress comparison."14 The reason was that the public perceived similarity in the food, operational manner, decoration, and/or menu. The Gelb survey concluded that "a substantial population of those who patronize quick-service Mexican restaurants, particularly those who have patronized Taco Cabana (where the survey was conducted), are likely to believe that Taco Cabana and Two Pesos are owned or operated by the same company."

[Fig.7] Gelb Survey: Reasons for confusion

As pointed above, the Gelb survey was conducted with the customers of Taco Cabana and Ta Casita, and these Taco Cabana stores were all located in Houston. Since the survey left out Two Pesos consumers, sampling is an issuehere. Gelb himself also warned against the broad interpretation of the survey data. Conversely, as Houston was the city where Two Pesos started to thrive and 61% of the respondents in a Taco Cabana store reported that they also visited Two Pesos, Gelb Surveymay well establish consumer confusion between Taco Cabana and Two Pesos. Due to such "tremendous overlap," Gelb claimed that the results would not have been different had the survey been conducted at Two Pesos stores as well, and that his conclusion about the likelihood of similarity "is extrapolatable into the general population."15 Taco Cabana’s attorney was quick enough to add that "You’re not suggesting a direct parallel, but just an appropriate approximation would probably expect the same general level of confusion?"16

Two Pesos’ survey, performed by Mr. Peterson, ("Peterson survey") was found "less helpful" by courts. The Peterson survey asked three questions to Two Pesos customers: 1) Why do you patronize Two Pesos Restaurants? 2) (Half) "Have you ever gone to another restaurant by mistake when you intended to go to a Two Pesos restaurant?" 3) (Other Half) "Have you ever gone to a Two Pesos restaurant by mistake when you intended to go to another restaurant?" The result was unsurprising. The Fifth Circuit found that "[p]redictably, a statistically insignificant number of people confessed to what would appear to be rather a silly mistake."17

Undiscouraged, Peterson even testified that the actual confusion could have been less likely because one respondent of the survey said he happened to arrive at Two Pesos by taking a wrong turn. Peterson claimed such mistakes proved that an individual’s choices of Two Pesos over Taco Cabana "have nothing to do with trade dress."18 Astonished, the Fifth Circuit stated that "[s]uch responses … suggest that people did not understand what the question meant by ‘mistake,’" and found that Peterson survey merely sought "whether consumers can read signs and menus that identify different restaurants.

Still, surveys would not be the sole weapon of a lawyer in order to prove likelihood of confusion. The Fifth Circuit stated that survey data is one indicia of confusion, and other indicia include "the similarity of the trade dress; the coincidence of products, markets, and advertising media; and [the defendant’s] intent in adopting its trade dress." When one of the Two Pesos owners argued that he obtained the idea of Two Pesos from Alfonso’s,another Mexican restaurant in San Antonio, the Taco Cabana owner testified that such a claim was not likely because Alfonso’s was not similar to Two Pesos. "[I]t doesn’t have garage doors. It doesn’t have awnings. It has a tile roof. It has a sawtooth or jagged roofline. And, of course, I know that … [t]hey have all their food delivered in trucks early in the morning… There’s very little prepared on the premises." It appears that the district court considered this testimony in determining the prominent features of Taco Cabana’s trade dress. When the district court gave construction orders to Two Pesos, the orders specifically referred to garage doors, awnings and roofline – all identified by the Taco Cabana owner as features of Taco Cabana.19

C. Changes Ordered by the District Court

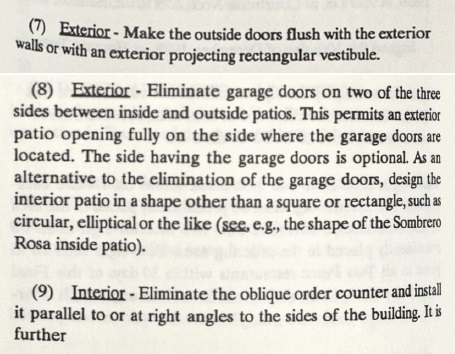

Based on the witness testimony and evidence, the district court found that the case was "exceptional [and] deliberate infringement and misappropriation of Taco Cabana’s trade dress," the court also gave construction orders to wipe out Taco Cabana’s trade dress.20 Two Pesos was ordered to incorporate detailed changes of four exterior parts and one interior part.

[Fig.8] District court's construction orders given to Two Pesos

For existing restaurants, the rate of construction was "at least ten restaurants per six months," and all the restaurants must have completed constructions within 18 months. For all the upcoming restaurants, the desired changes were more extensive: Two Pesos must have eliminated garage doors on two of the three sides and change the shape of the order counter (see (7)-(9)at Fig.8). Do you agree that the desired changes would not generate customer confusion?

Furthermore, the district court ordered Two Pesos to install a sign inside and outside Two Pesos restaurants, stating that "NOTICE: TACO CABANA originated a restaurant concept which Two Pesos was found to have unfairly copied. A Court Order requires us to display this sign to inform our customers of this fact to eliminate the likelihood of confusion between our restaurants and those of TACO CABANA." The court also precisely laid out how the signs look ("one inch black letters on a white background"), where the signs are placed ("The exterior sign … prominently placed in the area of the customer's entrance; the interior sign … prominently placed in the ordering area"), how long the signs are displayed ("within 30 days of this Final Judgment and shall remain in place for at least one year"). Later on, the United States Supreme Court also ordered Two Pesos to incorporate such detailed changes. The owners of Two Pesos decided to sell the business to Taco Cabana in 1993.

Footnote Sources:

1 While the jury awarded $934,300 for trade dress infringement and $150,000 for trade secrets misappropriation, the district court doubled the trade dress damage. The court also awarded attorney’s fees of $937,550. Taco Cabana v. Two Pesos, 932 F.2d 1113, 1117. (5th Cir. 1992).

2 Excerpts from Taco Cabana’s First Amended Complaint. Joint Appendix (No. 91-971) at 42. Two Pesos v. Taco Cabana, 505 U.S. 763 (1992).

4 JA at 114. Mr. Brinker developed the concept of Steak & Ale. JA at 124.

5 JA at 110. For more detailed explanations, see JA at 115-18.

10 Taco Cabana, 932 F.2d at 1118 (Internal marks omitted, quoting Fuddruckers, Inc. v. Doc’s B.R. Others, Inc., 826 F.2d 837, 884-43 (9th Cir. 1987)).

11 Only six days before filing suit against Two Pesos, the two owners of Taco Cabana divided the restaurant business and one of them began to operate under the name of Ta Casita. By cross-licensing, the two owners agreed to use the similar trade dress for the two businesses. Taco Cabana, 932 F.2d at 1117.

14 Yet, Gelb did not find the top category (They have the same food/Same things) was important in understanding the similarity issue because it was "just kind of a generalization" made by respondents. JA at 170.