For Further Study:

- United States v. Hearst

Memorandum and order denying motion to bar Hearst’s proffered psychiatric testimony

- Trial Testimony

Excerpt of Dr. Joel Fort’s Testimony

- Closing Argument of Mr.Bailey

- Bank Robbery

Hibernia Bank Robbery Clips

- Kidnapping

Tape recording of Patty Hearst after being kidnapped

- Stockholm Syndrome and Patty Hearst

- Causes of Stockholm Syndrome

- Coercive Persuasion

Coercive Persuasion and Attitude Change

- The Aftermath

Patty Hearst on Larry King Live on testifying against SLA members

Social Science and Coercion as a Defense in

Kidnapping Cases

Patricia Hearst: Kidnap Victim to Criminal?

Compiled by Lauren Bowman, Dominique Forrest, Malissa Osei

|

|

Introduction

Traditional psychiatric defenses used in criminal cases include insanity and diminished capacity. In United States v. Hearst, Patricia Hearst used the quasi-psychiatric defense of coercion after she was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army ("SLA") and put on trial for her participation in an armed robbery perpetrated by the SLA. Hearst’s lawyers relied on expert testimony to support this defense. Social science research formed the basis of this expert testimony and played a large role throughout the case. The legal issue in the case was whether Hearst’s "initial status as a kidnap victim and the subsequent treatment of her by her captors could have deprived her of the requisite general intent to commit the offense charged." This webpage explores the theories that support the defense of coercion and how the defense was used in the Hearst case.

Patricia’s Story

The Kidnapping

(http://movies.netflix.com/WiMovie/Patty_Hearst/70109246?locale=en-US)

On February 4, 1974, 19-year-old Patricia Hearst was kidnapped by the SLA from her apartment in Berkeley, California. Hearst was the granddaughter of William Randolph Hearst and the daughter of Randolph Hearst, both were influential in the newspaper industry. The goal of the SLA was to end the capitalist state. Eight days after Hearst’s kidnapping, the SLA released a tape recording to a radio station demanding that Randolph Hearst organize a multi-million dollar food drive. The tape recording also included a statement from Patricia asking her parents to follow the demands of the SLA. Fifty-nine days after Patricia’s kidnapping, the SLA released another tape recording. This time she was recorded stating, "I have been given the choice of being released...or joining the forces of the Symbionese Liberation Army and fighting for my freedom and the freedom of all oppressed people. I have chosen to stay and fight." Patricia also announced that she decided to take the name "Tania," the name of a woman who had once organized with Che, the famous Cuban revolutionary leader, in Bolivia.

The Robbery

(http://www.outsidelands.org/streetwise-noriega.php)

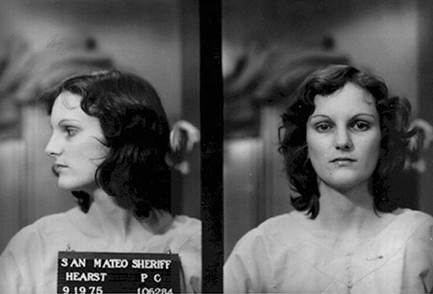

On April 15, 1974, Patricia aided the SLA in an armed robbery of San Francisco’s Hibernia Bank. Security tapes captured Hearst introducing herself as Tania and warning customers to stay on the floor. Hearst justified the bank robbery in a tape recording released after the bank robbery, "Greetings to the people, this is Tania. Our actions of April 15 forced the Corporate State to help finance the revolution. As for being brainwashed, the idea is ridiculous beyond belief. I am a soldier in the People's Army." Just a month after this, Hearst was spotted at another crime scene. Patricia fired shots in the direction of the store from a van parked across the street after SLA members William and Emily Harris were caught shoplifting ammunition from a sporting goods store. Patricia was arrested on September 18, 1975.

The Trial

(http://www.pulpinternational.com/pulp/entry/Patty-Hearst-Newsweek-cover-he-week-of-her-trial.html)

On February 4, 1976, Patricia was tried for armed robbery of the Hibernia Bank. Her defense lawyer, F. Lee Bailey, argued that Patricia had been brainwashed by the SLA. The jury had to be persuaded that Patricia had been coerced or brainwashed by the SLA. The difficulty with this defense was that Patricia, prior to her trial, had admitted joining the SLA even though they told her she could be released if she wanted to.

To overcome the evidence against Patricia, Bailey relied on the testimony of three mental health experts during the trial. These experts supported the defense’s argument that Hearst had been brainwashed by the SLA and that as a result of being brainwashed Hearst had participated in the group’s criminal activities.

Patricia was found guilty despite the defense’s efforts to prove their theory of coercive persuasion. It only took the jury one day to deliver the verdict. Patricia was sentenced to seven years in prison. However, she only served twenty-two months in prison. President Jimmy Carter released Patricia in February 1979. Bill Clinton granted Patricia a presidential pardon on January 20, 2001.

(http://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Carter-Asks-Clinton-To-Pardon-Patty-Hearst-2904317.php)

Sources:

Douglas O. Linder, Patty Hearst Trial, Famous Trials, (2007), http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hearst/hearsthome.html

Charles Patrick Ewing, Minds on Trial 31-43(2006)

The Theory Behind Coercive Persuasion

One of the first instances of the theory of coercive persuasion and brainwashing was brought forth when a large group of intelligence officers, psychiatrists, and psychologists recognized that during the Korean War "the Chinese had been able to sway many [American] soldiers to their way of thinking, as evidenced by reports of extensive collaboration, by propaganda broadcasts made by some of the prisoners, and by letters and other documentary evidence of collaboration." The beliefs and attitudes of American POWs had changed so drastically, that the term "brainwashing" was applied to their experiences. However, after analyzing the situation of the prisoners, researchers abandoned the term and opted for the more fitting term "coercive persuasion." Coercive persuasion was more fitting because the prisoners were "subjected to unusually intense and prolonged persuasion in a situation from which they could not escape."

In Coercive Persuasion, Edgar Schein, Inge Schneier, and Curtis Baker came to the conclusion that coercive persuasion involves the intertwining of a complex sequence of events occurring over a long time period. They labeled the events in three phases: unfreezing, changing, and refreezing. In order to successfully influence an individual via coercive persuasion, Schien et al concluded that there must be a motive for the individual to change, a source that shows the direction of change, and a reward for when the change occurs. Their study revealed that it is difficult to predict whether a particular prisoner will be susceptible to coercive persuasion tactics. Furthermore, while the model of coercive persuasion proposed by Schein et al was confined to the Chinese Communists, they also stated that the theory of coercive persuasion can be used in various contexts.

Richard Ofshe’s Key Factors of Coercive Persuasion

Richard Ofshe was a Professor Emeritus in Sociology at the University of California at Berkeley. His special interests include topics such as coercive social control, social psychology, and influence in police integration. In an article titled "Coercive Persuasion and Attitude Change" he noted the following factors relevant to coercive persuasion:

- Relying on intense interpersonal and psychological attack to destabilize a person’s sense of self in an effort to promote compliance.

- Using an organized peer group to achieve compliance.

- Employing pressure to promote conformity.

- Manipulating a person’s social environment to stabilize their behavior once it is modified.

Coercive Persuasion in the Hearst Case

In United States v. Hearst, Patricia Hearst’s defense team elicited expert testimony from witnesses in order to present the theory of coercive persuasion to the jury. The defense was not successful in this case. Stockholm syndrome, a closely related theory, may have been a stronger alternative. However, since Stockholm Syndrome was not fully developed at the time of the trial, it was not a viable defense.

Sources:

Edgar H. Schein, Inge Schneier, Curtis H. Barker, Coercive Persuasion: A Socio-psychological Analysis of the "Brainwashing" of American Civilian Prisoners by the Chinese Communists (1st ed. 1961), 7, 18, 283, 284.

Richard J. Ofshe, Coercive Persuasion and Attitude Change, http://www.rickross.com/reference/brainwashing/brainwashing8.html

University of California at Berkley, Sociology, http://sociology.berkeley.edu/professor-emeritus/richard-j-ofshe

The Origins of Stockholm Syndrome

Stockholm Syndrome, also known as Survival Identification Syndrome, is a phenomenon in which kidnapping victims display compassion or even loyalty toward their captors. The syndrome was first recognized after the 1973 Swedish bank robbery that gave it its name. For six days in August 1973, two thieves, Jan-Erik Olsson and Clark Olofsson, held four employees hostage at gunpoint inside the vault of a bank in Stockholm.

Image of bank hostages in Stockholm

(http://www.webmd.com/balance/news/20030313/what-kept-elizabeth-smart-from-escaping)

When the victims were released, their reaction shocked the world; they hugged and kissed their captors, one victim publicly declared his loyalty to the kidnappers. The origin of the term Stockholm Syndrome is often attributed to remarks made during subsequent news broadcast by the well-known Swedish criminologist and psychiatrist Nils Bejerot, who assisted the police during the Stockholm robbery. Bejerot and other behaviorists conducted research to see if the Stockholm incident was unique or if other hostages experienced a similar form of bonding with their captors as defense mechanism for survival. The researchers determined that the behavior was very common.

Causes of Stockholm Syndrome

- Believing one's captor can and will kill them.

- Isolation from anyone but the captors.

- Belief that escape is impossible.

- Inflating the captor's acts of kindness into genuine care for each other's welfare.

Victims of Stockholm Syndrome suffer from severe isolation and emotional and physical abuse demonstrated in characteristics of battered spouses, incest victims, abused children, prisoners of war, cult victims, and kidnapped or hostage victims. Each of these circumstances can result in victims responding in a compliant and supportive way as a tactic for survival.

Stockholm Syndrome, Coercive Persuasion, and the Legacy of Patricia Hearst

The mysterious kidnapping of Patricia Hearst in 1974 shocked the United States just a short year after the landmark Stockholm robbery. At the time, psychiatrists in the U.S did not recognize or understand the nature of Stockholm syndrome. Consequently, when the lead defense counsel for Ms. Hearst decided to adopt a version of Stockholm Syndrome for her defense, he was met with great skepticism. During the trial, a team of mental health experts testified (two of whom participated in the initial court appointed evaluation of Hearst) to the validity if Hearst’s symptoms and likened her experience to that of prisoners in Maoist China. At the time, the theory of Stockholm Syndrome was not sufficiently recognized and its symptoms were extremely difficult to quantify. This prevented the theory from qualifying as psychiatric defense. So although Bailey assembled a team of experts who would eventually bec.ome instrumental in the development of thought persuasion theory, in 1974 the scientific community was not prepared to acknowledge it. The outcome of the Hearst trial exemplifies the nation’s unwillingness to rely on this form of scientific evidence.

Today Stockholm Syndrome has become significantly more recognized in the scientific community. There are now accepted diagnostic criteria for identifying Stockholm Syndrome, and the theory has been used by doctors and the media to explain national cases such as the Elizabeth Smart kidnapping. According to mental health experts, victims of Stockholm syndrome generally stand a good chance of recovering, but the prognosis and road to recovery depend on the nature and intensity of the ordeal, and the victim's individual ability to cope. Nevertheless, some critics continue to insist that Stockholm Syndrome, coercive persuasion, and other forms of thought reform theory are largely a figment of the media's imagination.

Sources:

Charles Patrick Ewing, Minds on Trial 31-43(2006)

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:PattyHearstmug.jpg)

Expert Testimony at Patricia's Trial

Below are excerpts from the experts who testified at Patricia’s trial. These excerpts demonstrate the competing views of what happened to Patricia Hearst and the difficulty the defense had in formulating a successful defense.

Defense Experts

Dr. Jolyn West

Professor and Chairman of Psychiatry at UCLA

Dr. West was well known for his extensive experience in studying prisoners of war. At Patricia’s trial, Dr. West described the body of scholarship on coercive persuasion and brainwashing. He also presented the results of his evaluation of Patricia.

West’s testimony on the effect the SLA had on Hearst:

"[I]n most of the POW’s that I studied, the results were very similar to that in her case. In other words, the desired behaviors were achieved. They did what they were told to do, they said what they were told to say."

"She was persuaded to take on a certain role and she complied with everything they told her to do. If they wanted her to clean a shotgun, she cleaned a shotgun. And if she took part with the group, she just tried to blend in with the others and behave in a fashion that she understood was expected if she was to be accepted. For her, it was to be accepted or to be killed."

"She thought that they were going to kill her in the bank unless she did exactly what they wanted and she was so paralyzed with fear that she didn’t even do everything they wanted. But, she did enough to suit them."

Sources:

United States v. Patricia Hearst, trial transcript, reproduced in The Trial of Patty Hearst (San Francisco: the Great Fidelity Press, 1976), 258, 257-258.

Charles Patrick Ewing, Minds on Trial 36-37(2006).

Dr. Martin Theodore Orne

Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and Director of the Unit for Experimental Psychiatry at the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital

Dr. Orne used tactics used in other studies to determine whether Patricia Hearst was lying about the coercive persuasion that took place.

"I tried to use the kind of procedures which we found effective in some of our laboratory studies and that is to try to, in an interview, imply subtly what might be good answers which, typically, somebody trying to play a role would pick up on because they would make sense, and found to my surprise that this girl really was troubled and would be trying to relate the events that had transpired."

"The intended general strategy was to allow her to say things which would make things look better for her. For example, in talking about the experience in the bank robbery, I suggested that perhaps she had been very scared . . . I would then say, ‘Well, this must have been terribly frightening to you’ which is a kind of leading question -- and to which again someone simulating would say, "Yes, I was terribly scared." [T]his is where I was puzzled because all I could get was the answer, "I don’t remember how I felt. It was like a dream. Which struck me as something very different from what I would have gotten from somebody simulating."

Source: United States v. Patricia Hearst, trial transcript, reproduced in The Trial of Patty Hearst 294, 296, 299-300 (San Francisco: the Great Fidelity Press, 1976).

Dr. Robert Jay Lifton

Professor of Psychiatry at Yale University

At the time of the Hearst trial, Dr. Lifton was considered one of the first psychiatrists to have conducted extensive research on thought reform psychology. At trial, Dr. Lifton provided insight on a continuing study he was conducting regarding the effects of coercive persuasion on victims in China and Russia.

Describing the process of coercive persuasion:

"By and large it’s much easier to break people down then it is to rebuild them. In fact, that was one of the real lessons I learned from this continuing study. The mind is rather fragile. It can be broken down."

"At that point, (after physical and psychological abuse) there’s a desperate need for some way of adapting, for some way of finding a path to survive, to survive both physically and psychologically. And, at that point, the coercive persuaders, those manipulating the process, tend to institute a policy of leniency."

"In the Chinese prisons where the people whom I studied had been, there was tremendous emphasis upon the reform of thoughts right after the process of leniency; but there was also the completion of the confession. By that point, the prisoner feels a certain amount of relief and a tremendous eagerness to comply in any way possible and necessary that will enable him to survive."

Describing the effects of coercive persuasion on Hearst:

"She was thrust into this . . . narrow but totally controlled environment after she was kidnapped by the SLA group in which they not only controlled all communication going in and out, and especially during the first few months, but also gave her the sense that they were omniscient, they knew everything, all the details about her family, their holdings, about her past life, and she began to get the sense that they knew-- she said to me ‘I confessed to anything because they seemed to know everything about me anyhow.’ "

Source: United States v. Patricia Hearst, trial transcript, reproduced in The Trial of Patty Hearst (San Francisco: the Great Fidelity Press, 1976), 314, 316-317.

Dr. Nicholas Groth

Chief Psychologist for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts

Dr. Groth was called as a surrebuttal witness for the defense. Groth, who was once employed by Dr. Harry Kozol, gave testimony to show possible bias on the part of Dr. Kozol.

Groth testified that the Dr. Kozol had stated prior to the arrest of Patricia Hearst that the Hearst’s were "disgusting and venal" and that Mrs. Hearst was a "whore." Further, Groth alleged that Kozol told him "if you had grown up in a family like Patricia, you would understand what she is rebelling against. They are pigs."

Sources: United States v. Patricia Hearst, trial transcript, reproduced in The Trial of Patty Hearst (San Francisco: the Great Fidelity Press, 1976), 554, 559-560.

Prosecution Experts

Dr. Joel Fort

Physician, lecturer, and consultant

While Dr. Fort was not a psychiatrist, he had testified in over two hundred criminal cases across the nation. Fort’s testimony branded Hearst as a willing member of the SLA.

Fort’s testimony rejecting the defense’s brainwashing theory:

"She was a strong, willful, independent person, bored dissatisfied, in poor contact with her family, disliking them to some extent, dissatisfied with Steven Weed [her fiancé] with whom she had been about three years at the time of the kidnapping, and the interaction of that, that kind of vacuum, of something missing, a missing excitement, a missing sense of purpose in life with what seemed on the surface to be offered by the SLAers as she got to know them and as she became impressed, as she describes in [an] interview, with her commitment, and as she described to me being impressed with their willingness to die for their beliefs, I think that action was very important to her."

"[R]ather than being glad to return to… society, being glad to be back or have the opportunity to be with past friends or to renew past family contact . . . she was upset that she had been arrested."

The biggest critique of Fort’s testimony was that he did not have strong credentials. Hearst’s defense lawyer highlighted the fact that he had never published anything on brainwashing or coercive persuasion.

Sources:

United States v. Patricia Hearst, trial transcript, reproduced in The Trial of Patty Hearst (San Francisco: The Great Fidelity Press, 1976), 437, 440.

Charles Patrick Ewing, Minds on Trial 40(2006).

Dr. Harry L. Kozol

Diplomat of the American Board in both psychiatry and neurology

Dr. Kozol was a licensed physician with a specialty in psychiatry and neurology. He was called to the stand to testify as to whether Patty Hearst committed the robbery and joined the SLA of her own free will.

Kozol’s testimony calling into question Hearst’s theory of coercive persuasion:

Q [Mr. Browning]: "Now doctor . . . you have some familiarity with prisoners of war, having treated some, I believe, and read the literature on the subject. Are you familiar with any case in which a prisoner of war has committed any violent acts against his or her former comrades at the behest of the captors?

A [Dr. Kozol]: "No. I don’t know of a single prisoner of war." "I have never read any of our Air Force personnel ever having been put on trial . . . for having assisted the Chinese or North Koreans."

"I think she entered the bank voluntarily in order to participate in the robbing of the bank. This was an act of her own free will."

"In fact, she wrote somewhere that she did not trust [the SLA] at the beginning, that she was suspicious of them, but after a while, she came to feel that she trusted them. I think the fear had gone, it surely disappeared by the time she made the statement that she had decided to stay with them."

"Mr. Bailey, I don’t think the most accomplished actress on earth could, in such a short period of rehearsal, if you want to put it that way, said the things Patricia Hearst said the way she said them without meaning them, without having them come from her own heart, if not also from her own mind."

"I imagine [the kidnapping] should have been terrifying, but I did not get the sense from Patricia that it was terrifying as much as it was numbing, as though she was resigned."

United States v. Patricia Hearst, trial transcript, reproduced inThe Trial of Patty Hearst, 519, 520, 531, 532 (San Francisco: The Great Fidelity Press, 1976)

Judge’s instructions to the jury

"It is your duty to determine the facts, not from what this witness says, but from what you know about the facts. [Y]ou and you alone have to make this ultimate decision and no psychiatrist, no judge, no lawyer or no one else should invade that province."

"[O]ne of the issues to determine the guilt or innocence of the defendant is going to be whether or not the defendant was coerced at the time the alleged offense was committed, and to what extent that may go to the question of guilt or innocence."

"The purpose of the psychiatric testimony is to advise you. [Y]ou may give [it] such weight as you deem [it is] entitled to."

Sources:

United States v. Patricia Hearst, trial transcript, reproduced inThe Trial of Patty Hearst, 519, 520, 531, 532 (San Francisco: The Great Fidelity Press, 1976)

Conclusion

In the Hearst trial the testimony given by experts was extensive but also inconsistent as demonstrated by the preceding excerpts. At times throughout the trial, the jury may have viewed Hearst as a victim of the SLA. However, in the end the defense’s expert testimony was not enough to vindicate her. We believe that the jury may have viewed the social science evidence as underdeveloped and unconvincing. The case, nonetheless, provides an interesting study of the potential impact and problems that social science can have in forming a defense.