For Further Study:

- Access Official Documents Filed in the Tsarnaev Trial

- Guide to the Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Trial

- The Charges Against Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Explained in Plain English

- New York Times Article on the Denial of Tsarnaev's Change of Venue Motion

- Copy of the Bronson Report from the Wall Street Journal

- New York Times Debate on Whether to Move Trial

Change of Venue Motions in the Tsarnaev Trial

Compiled by Ariel Atlas, Johanna Bachmair, and Brian Musto

I. Introduction

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is one of two brothers who were accused of planting multiple bombs that exploded at the Boston Marathon on April 15, 2013. According to a Boston Globe report, three people were killed and more than 260 were reported injured as a result of the detonation of the bombs.1 Although his brother Tamerlan was killed during a shootout with authorities in the days following the Marathon, Dzhokhar was eventually captured on April 19, 2013. He has pled not guilty to all 30 charges leveled against him, including using and conspiring to use a weapon of mass destruction resulting in death.2

Tsarnaev and his attorneys have requested that his trial be moved out of Boston because he believes the level of local prejudice on the issue will make it impossible for him to get a fair trial if the location is not moved. While the United States Constitution provides that the trial of a criminal case will be held in the State where the said crimes are alleged to have been committed,3 the Sixth Amendment guarantees a criminal defendant the right to a trial by an impartial jury of the State and district where the crimes were supposedly committed.4 According to the Supreme Court, however, place-of-trial prescriptions do not impede transfer to a different district if the defendant requests it and extraordinary local prejudice will prevent a fair trial.5 In Skilling v. United States, the Supreme Court analyzed the circumstances under which a presumption of prejudice would arise and warrant a change of venue, indicating that prejudice is only to be presumed in the most extreme cases.6

The Skilling standard still used by courts identifies four factors as determinative as to whether the defendant demonstrated a presumption of prejudice that requires a venue transfer: 1) the size and characteristics of the community in which the crime occurred and from which the jury would be drawn; 2) the quantity and nature of media coverage about the defendant and whether it contained “blatantly prejudicial information of the type readers or viewers could not reasonably be expected to shut from sight”; (3) the passage of time between the underlying events and the trial and whether prejudicial media attention had decreased in that time; and (4) in hindsight, an evaluation of the trial outcome to consider whether the jury’s conduct ultimately undermined any possible pretrial presumption of prejudice

While it is not the goal of this webpage to determine if Tsarnaev should have received the change of venue he has requested, it will remain important to review his arguments and reasoning, and examine the social science tools utilized by the parties in this case. Perhaps the most extensive utilization of social science in this case was submitted by the Defense, which submitted data from a public opinion survey of four jurisdictions, as well as an expert report. Edward Bronson, Professor Emeritus of Political Science at California State University, Chico analyzed the amount of pretrial prejudice in Boston; Springfield, Massachusetts; Manhattan; and the District of Columbia. The details of his study will be analyzed below.

While most experts seems to think a change of venue should have been granted, there are some dissenting opinions. A good example laying out some of the most common arguments on both sides can be found in the New York Times article “Room for Debate: When a Local Jury Won’t Do”7. Laura Appleman, professor of criminal law at Willamette University, says the trial should not be moved because the local community also has interests under the Constitution, and it should be up to them to decide Tsarnaev’s fate for a crime that affected so many in the community.8 On the flip side, professor Thaddeus Hoffmeister says the trial should be moved because he doubts jurors could find Tsarnaev not guilty and comfortably return to live as usual in their hometown.9

Other common arguments are that, with the national coverage given to the Boston Marathon bombing, no place in the United States will be completely devoid of jury prejudice. We live in a world with a 24-hour news cycle, and the countless avenues through which Americans receive their news only increase the chance that people have seen enough about Tsarnaev to have already made a decision on his fate. A counter to that would be, if you are not going to change the venue of the Tsarnaev trial then is their any scenario where venue would be changed in that jurisdiction? There is no clear cut answer to most of these dilemmas, but strong arguments persist.

Other high profile trials have taken place in the communities where they occurred. After the World Trade Center bombing in 1993 which killed six and injured over a thousand people, the six co-conspirators were tried in the Southern District of New York, even though the first change-of-venue motion was filed less than a year after the bombing.10 The district court denied a change of venue motion for Zacharias Moussaoui, a man prosecuted in the Eastern District of Virginia, near the Pentagon, for the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.11

On June 18, 2014 Tsarnaev petitioned Judge O’Toole of the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts to transfer his trial to a place outside of Massachusetts pursuant to the Fifth, Sixth, and Eighth amendments and Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 21.12 Tsarnaev’s lawyers claimed that pretrial publicity and public sentiment required the Court to presume that the pool of prospective jurors in the District is so prejudiced against him that gathering an impartial jury in Boston would virtually be impossible.

On September 24, 2014, the district court denied the motion. In its order, the court addressed the evidence and, after analyzing the Skilling standard, concluded that Tsarnaev failed to demonstrate that pretrial publicity rendered it impossible to find a fair and impartial jury in the District of Massachusetts.

On December 1, 2014, Tsarnaev filed a second motion to change venue, arguing that the need for a change of venue had increased because of continuing prejudicial publicity in the media and alleged leaks of information by government sources. On December 31, 2014, without waiting for the district court's written decision on the second motion, petitioner filed his first mandamus petition the Court of Appeals. On January 2, 2015, while the Court of Appeals continued to consider the mandamus petition, the district court issued its written decision on the second venue motion, noting that the new motion did not raise any genuinely new issues and concluding that no presumption of prejudice had arisen that would justify a change of venue. On January 3, 2015, the Court of Appeals denied the motion to stay jury selection and the first petition, concluding that Tsarnaev had not made the extraordinary showing required for mandamus relief.

II. Survey Data: Analysis of the Bronson Report

In the Bronson study (See Declaration of Edward J. Bronson, United States v. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, D. Mass. No. 12-10200-GAO (filed Aug. 7, 2014)) the expert surveyed participants from four locations organized by federal courthouse: the Eastern and Western Divisions of Massachusetts, the Southern District of New York, and the District of Columbia. Ultimately, the participants who responded in Boston ranked as the most prejudiced on all of the critical measures: case awareness, case knowledge, pre-judgment of guilt, case-specific support for the death penalty, and case salience.

The target size for the venues surveyed was 300 qualified interviews for the Boston area and 200 for the other three sites. The random-digit-dialing system was used to obtain a likely representative sample of target population: the jury pool in that division or district. The screeners were used to determine that respondents were jury eligible.

The demographic questions were included in the survey so that we could compare the survey demographics with the demographics of the actual residents.

Def. Guilty |

Death Penalty |

Partic./knew 2013 |

Ever Partic. |

|

Boston |

57.9 |

37.0 |

51.9 |

49.3 |

Springfield |

51.7 |

35.0 |

19.0 |

16.7 |

Manhattan |

47.9 |

27.6 |

9.4 |

7.8 |

D.C. |

37.4 |

19.0 |

11.8 |

5.6 |

Def. Guilty = Those who recognized the case were asked if they believed the defendant was definitely guilty, probably not guilty, or definitely not guilty, probably guilty, probably not guilty, or definitely not guilty.

Death Penalty = Those who recognized the case were asked if they believed that if the defendant were convicted he should receive the death penalty or life without possibility of parole.

Partic. 2013 = Respondents were asked, Do you or did someone you know participate in or attend the Boston Marathon held last year in 2013?

Ever Partic. = Have you ever participated in or attended the Boston Marathon?

Media Coverage

The study also examined the coverage in major newspapers in each of the four venue areas, the Boston Globe, the Springfield Republican, the New York Times, and the Washington Post. Although other media, including electronic, social media, and many other newspapers also covered the case, these newspapers were selected as major sources in the selected venues.

Newspaper |

Number of Articles |

Front Page |

Boston Globe |

2,420 |

793 |

Springfield Republican |

324 |

148 |

New York Times |

467 |

88 |

Washington Post |

427 |

111 |

As can be seen from the above table, the number of newspaper articles collected from only the Boston Globe and covering a period of a bit less than 15 months is 2,420. That is extraordinarily high.

By comparison, in the Oklahoma City Bombing case, there were 2,213 articles – some 200 fewer than in this case, and that press collection involved a longer period of time, and there were multiple newspapers throughout the entire state, not just one newspaper in Oklahoma City.

“In the many change of venue motions in which I have been involved, and which dealt with high-profile cases, the median number of articles has been 91.” (See Declaration of Edward J. Bronson, United States v. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, D. Mass. No. 12-10200-GAO (Aug. 7, 2014).

Nature of Coverage

The four elements in that hierarchy are publicity that is (1) inflammatory, (2) inadmissible at trial, (3) inaccurate, and (4) likely to generate a presumption of guilt.

Other Interesting Data

The survey done in this case showed that in the four venues surveyed, almost two-thirds (Q7f, 63.8%) of all respondents said they have “talked about the case with relatives, friends, or co-workers.”

The survey did a count of many of the various references to the death penalty in the Boston Globe’s coverage of the case. There were 441 references to “death penalty,” 76 references to “capital punishment,” 23 references to “death sentence,” 64 references to “execution,” 16 references to “lethal injection,” and 12 references to “put to” or “sentenced to” “death.”

The Globe used the term “monster” 34 times about him. There were 627 references to “terrorist” (although some were referring to some other terrorist attack or other uses). There were eight characterizations of him as depraved (or depravity), 10 references to him as callous, and a few employing the words vile, revile, or devil.

The motto “Boston Strong,” which was mentioned 421 times in the Globe appeared on T-shirts, other shirts, uniforms, including sports, some with the 617 area code.

Conclusions from Report

Examining the overall results of the survey, it is readily apparent that Boston residents are a significantly more biased jury pool than the other three venues. On every one of the major categories (guilt, death penalty, fact-specific knowledge, and salience) it was the highest scoring in prejudice.

Washington, D.C. is the least biased venue of the four, and there is a substantial gap between it and the other three venues, as can be seen in the discussion and tables above.

“The data summarized here leave no doubt in my mind that by almost any measure, the case should be transferred out of the District of Massachusetts.”

III. Reactions of the Prosecuting Attorneys and the Judge to the Social Science

The defense first moved to change venue on June 18, 2014, relying on survey results indicating that respondents in the District of Massachusetts overwhelmingly presumed Mr. Tsarnaev’s guilt, had prejudged the penalty that should be imposed, and that many of the respondents had a connection to the 2013 Boston Marathon. At that point the defense did not name Professor Bronson as the survey’s creator, although they later revealed his identity. On July 1, 2014, the prosecution responded, criticizing the survey poll results as unreliable and unexplained, and vigorously protesting the motion to change venue.

The defense replied a few weeks later, identifying Professor Bronson as their expert on change of venue and citing specific survey data as well as Professor Bronson’s expert report to support their motion. Professor Bronson declared that even though funding issues forced him to conduct the survey in a very short timeframe, his review and analysis of the pretrial publicity and the survey results led him to believe that the Court should grant a change of venue. On August 25, 2014, the prosecution once again forcefully opposed the motion in a sur-reply, this time attacking Professor Bronson’s credibility as well as the survey. A few days later the defense filed another reply, as well as a declaration by Professor Neil Vidmar, another expert in the field, stating that Professor Bronson’s survey methodology and results were valid, representative, and scientifically acceptable. The Court struck the defense’s reply and Professor Vidmar’s declaration because they were filed without leave. The Court later rejected the defense’s motion to re-file the materials. Finally, the Court denied the motion to change venue on September 24, 2014.

On December 1, 2014, the defense filed a second motion to change venue and once again included Professor Vidmar’s declaration. To support this motion the defense included new evidence, such as analysis of media reports published after the initial survey was completed. They argued that this evidence demonstrated that the nature and extent of continuing pretrial publicity required a change of venue.

The Court denied the second motion on January 2, 2015. It stated that the defense had merely provided additional information to support its earlier, unsuccessful argument, making this a motion for reconsideration. Further, the Court rejected Professor Vidmar’s attached declaration—now for the third time. The Court maintained that the new survey data, which analyzed more recent media reports, did not present anything “genuinely ‘new,’” making the motion for reconsideration procedurally deficient.

The Court also rejected the second motion for change of venue on the merits. Judge O’Toole once again criticized the defense’s media analysis, stating that “[t]he survey continues to be flawed for the same reasons.” Namely, he maintained that the survey used overbroad search terms and failed to distinguish between inflammatory and factual articles. Judge O’Toole noted the defense’s reiteration that Professor Bronson’s declaration supports a change of venue, but refused to reconsider a matter that he had already considered and rejected. The Court denied the second motion to change venue on January 2, 2015. The next day the First Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the defense’s application for a writ of mandamus, holding that they had not met the extraordinary showing required to justify mandamus relief.

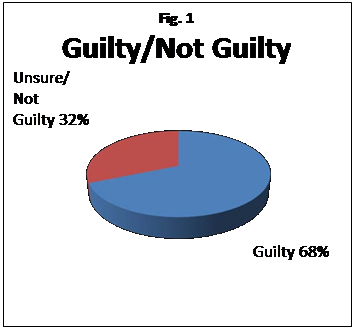

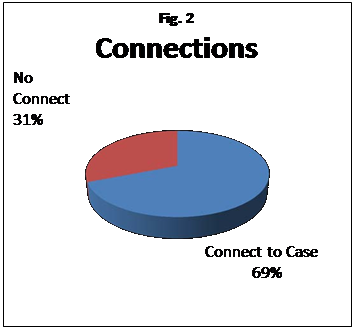

On January 22, 2015, the defense filed a third motion for change of venue. Notably, this time they included a supporting memorandum that excerpted data from the questionnaires completed by prospective jurors. The memo reports that the currently sealed questionnaires indicated that 85% of the prospective jurors believe Mr. Tsarnaev is guilty or have some self-identified “connection” to the case, or both, with 68% of prospective jurors already believing that Mr. Tsarnaev is guilty, “before hearing a single witness or examining a shred of evidence at trial,” and 69% having “a self- identified connection or expressed allegiance to the people, places, and/or events at issue in the case.” The defense argued: “stronger support for a finding of presumed prejudice in Boston is difficult to imagine.”

![]()

The defense’s supporting memo also included select responses to the questionnaires. For example, Juror #301 responded to question 98, “anything else we should know,” by stating “we all know he’s guilty so quit wasting everybody’s time with a jury and string him up.”

The prosecution again staunchly opposed the motion to change venue, citing its previous arguments against the earlier motions and stating that the new partial analysis of the completed juror questionnaires only demonstrated that thorough voir dire would be required to identify proper jurors. The Court denied the third motion on February 6, 2015, “for reasons both old and new.” Judge O’Toole referenced his previous orders and added that the voir dire process was working well to identify suitable potential jurors capable of being fair and impartial. He also noted that the defense’s use of quotations from the confidential juror questionnaires was improper and that he had placed the unredacted memorandum under seal because he had assured the jurors that any sensitive information would remain confidential permanently.

On February 27, 2015, the First Circuit Court of Appeals denied the defense’s second petition for writ of mandamus, although Circuit Judge Torruella strongly dissented.

On March 2, 2015, the defense made a fourth motion for change of venue, after voir dire was completed, based in part on the additional information about potential jurors revealed by the voir dire process. The prosecution responded that day, referring mainly to its previous arguments, but also alleging that the defense erroneously interpreted and framed the survey data. The Court has not yet decided the fourth motion for change of venue.

IV. Conclusion and Recommendations

To provide guidance on whether the Bronson study was adequate to answer the legal question at hand, the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence should be consulted. The Reference Manual provides guidance to courts in reviewing studies. The Manual makes clear that a study should provide information about a relevant population. The study should then select a sample that accurately reflects that population. Questions should be phrased clearly and precisely.

Given the short time frame, the Bronson study was a fairly comprehensive study. It was useful in addressing the legal issue and also provided a concrete solution for the judge if he decided to move the trial. The study, as it was created, was an effective way of presenting the problems with the current trial location. It analyzed data of individuals from four different locations and not just Boston, which was helpful to show differences in the various regions of the country. The country could have also presented data from additional locations to give the judge a wider range of options for moving the case.

It was also helpful that Bronson addressed the question whether voir dire could solve the problem in the case. Bronson claimed that jurors in the Boston area who have no knowledge or connections to the events are hardly individuals who represent the cross section of the community. Bronson also acknowledged that moving this trial would take several months and that, if the case were moved after voir dire, it could create additional publicity and require costs.

The review of media coverage was also very persuasive. Bronson’s ability to pull out parts of news articles was very persuasive. He emphasized that the problem isn’t just with the number of articles and news coverage but the language used in these articles. One major flaw with the media coverage part of the study was that it did not take into account the fact that media coverage generally is so much greater now.

The study did not provide denominators for how many articles total are printed in these periodicals or whether these numbers are high in context to other major events that have occurred. Additionally, it would have been more ideal if the study could measure how many people viewed the individual articles (on the Internet for example), not just how many were printed or published.

Including data from juror questionnaires in the defense’s motions was a useful way to show the judge that voir dire was not proceeding as they would like it to. However, it is easy for the information to be taken out of context and only the most exaggerated juror responses to be included in the motions. The parties should be sure to portray a balanced and accurate picture of how jury selection is going.

Social Science in Change of Venue Cases

Social science can be useful for answering a legal question such as this one in a high profile case. Although there is an obvious disconnect between asking jurors whether they have pre-judged guilt or feelings on the death penalty in a survey and the way they will react in a courtroom.

It is also very important to scrutinize exactly how the questions are being asked in these surveys as to make sure that leading questions are not skewing the results. Analyzing media coverage and pretrial publicity is helpful, but it assumes that individuals read and are influenced by the media.

1 Kotz, Deborah (April 24, 2013). "Injury toll from Marathon bombs reduced to 264". Boston Globe.

2 Accused Boston Marathon Bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Smiles in Court, Pleads Not Guilty". American Broadcasting Company. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

7 Room for Debate: When a Local Jury Won’t Do, NY Times, Jan. 7, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2015/01/07/when-a-local-jury-wont-do.